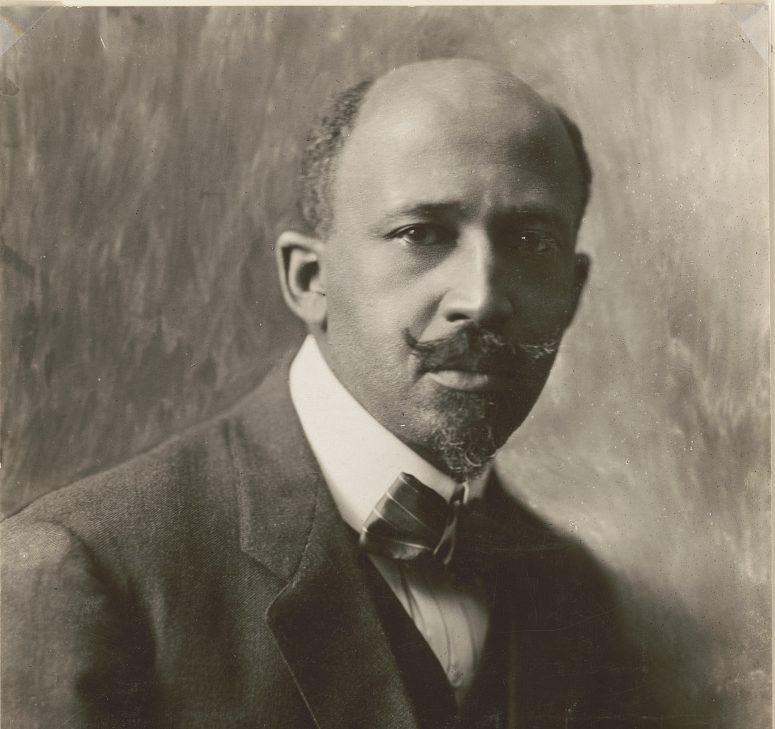

An Alternative View of Du Bois’s Talented Tenth

*This post is part of our online forum on W.E.B. Du Bois @ 150.

W. E. B. Du Bois published one of his most well-known and widely debated ideas in his 1903 essay titled “The Talented Tenth.”1 In it, he argued for the higher education of a tenth of the Black population from among whom would come the leaders of the race. Many scholars have concluded that it was an elitist theory that privileged the Black elite at the expense of all others. This discussion, however, offers a different perspective based on Du Bois’s training in philosophy and contends not only that his Talented Tenth was a parallel to Plato’s Philosopher Rulers (in The Republic, especially parts III, IV, VII, VIII), but that it was a radical proposal about how to reorder a society that restricted Black people’s opportunities, denied them civil rights, and even took their lives seemingly on a whim.

In Plato’s ideal republic, there was, indeed, a hierarchical society at the top of which were the Rulers who made the laws, organized the economy, and did things that we think of as in the purview of “the government.” After the Rulers and their Auxiliaries (who executed and enforced the rules), was the third group of people—workers. They included carpenters, bakers, shoemakers, and a variety of people of meager means, but workers also consisted of teachers, physicians, business owners, and other professionals. Some of these workers were people of substantial means, but the Rulers were obligated to prevent the development of extremes of wealth and poverty among individuals. They also had to make it possible for all people to live life. Their most important job was to create a good—just—society, making the Rulers a more ennobled class of people than we have regularly assumed them to be.

Even the process of their becoming leaders, mitigated the possibility of the Rulers becoming an exclusive clique. Wealth, family, and connections could not guarantee one a place among Plato’s Rulers, and neither poverty nor the lack of social connections or a lofty family pedigree could bar one from the group. The Rulers came to their position based on their education, experience, disposition, and character, and anyone could ultimately become one because everyone started out in the same educational system, pursuing the same course, advancing according to their ability. After finishing the formal schooling process and completing a mandatory two-year military stint, the graduates worked for the next fifteen or so years, during which time some of them would gain the experience, vision, patience, courage, wisdom—the character—to be among those from whom the Philosopher Rulers would come. It was a true merit system.

People could, however, be excluded from the leadership positions. A person’s desire to become a ruler could effectively eliminate him from the potential candidates. People who wanted to be rulers probably lusted after power and would not likely make good leaders. One who aspired to being rich would not be chosen. And those who were chosen could not accept pay for the work; money could spoil their vision, make them self-interested, and render them too vulnerable to special interests to be involved in politics. The primary concern of those who would be Rulers had to be the good of the group, the Republic. The potential and actual members of this group simply had to be talented, selfless, manifest certain abilities and dispositions, and be committed to goodness or justice.

Du Bois’s and Plato’s proposals further challenge the charge of elitism. First, both insisted on having publicly funded schools and colleges available to all and adequate training in all areas of work, including those that did not require a university education. Both men were adamant about the danger of installing people in positions for which they were not trained. Still, both proposals saw higher education as especially important. The ability to think for oneself was important to both philosophers, and both understood that the goal of education was not the work that it trained people to perform, but the life that work created. As Du Bois put it in 1903, “we may build bread winning, skill of hand and quickness of brain, with never a fear lest the child and man mistake the means of living for the object of life.” And it was the college-trained teachers who would keep those means directed toward the proper ends. For Du Bois, the job of these teachers was “to leaven the lump, to inspire the masses, to raise the Talented Tenth to leadership.”

In 1948, Du Bois reflected on and amended his original ideas about the Talented Tenth in a speech before the Boulé (Sigma Pi Phi), arguably the most elite Black organization in the country at the time. He was more, not less, insistent on the importance of The Talented Tenth. He wrote, “Willingness to work and make personal sacrifice for solving these problems [lynching, disfranchisement, segregation] was of course, the first prerequisite and sine qua non.” He added, “I did not stress this [in 1903], I assumed it.” He encouraged the expansion of the fraternity that he was addressing, but insisted that wealth should not be the only criteria for membership:

This new membership must not simply be successful in the American sense of being rich; they must not all be physicians and lawyers. The [people] . . . admitted must be those who . . . do not think that private profit is the measure of public welfare.

He sought “honest” and “self-sacrificing” men, describing it as “a question of character” and about which he admitted, “I failed to emphasize in my first proposal of a Talented Tenth.” Further challenging the charge of elitism, Du Bois made it clear that he was not counting on the Boulé members to fulfill the mandates of his Talented Tenth. He announced: “What the guiding idea of Sigma Pi Phi was, I have never been able to learn. I believe it was rooted in a certain exclusiveness and snobbery for which we all have a yearning even if unconfessed.” He accused them of manifesting an “unconscious and dangerous dichotomy” of possessing an “identity with the poor” while “act[ing] and sympathiz[ing] with the rich.”

He ended the commentary with a profoundly pessimistic declaration that simultaneously reflected badly on the character of the Boulé members: “Naturally, I do not dream that a word of mine will transform, to any essential degree, the form and trends of this fraternity, but I am certain the idea called for expression and that the seed must be dropped whether in this or other soil today or tomorrow.” In short, if the Boulé members saw themselves as de facto members of Du Bois’s Talented Tenth, they were clearly mistaken.

If we view it in a particular way, Du Bois’s Talented Tenth proposal was actually quite radical. Consider, for example, that according to 1986 U. S. Census data it was not until 1984(!) that at least ten percent of Black Americans over the age of 25 had completed at least four years of college (p. 134). What if ten per cent of Black Americans had been college trained three generations earlier (when Du Bois first proposed The Talented Tenth) and trained for and committed to the creation of a good—just—society? Would it have taken two whole generations more for the eruption of the modern civil rights movement or the passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts? Would they have even been necessary?

Even though it is a question that we cannot answer, considering the segregation, disfranchisement, underfunding of Black public schools, and the specter of lynching that most Black people lived every day at the turn of the twentieth century, it is a question worth considering. In that context, it is difficult to imagine a more radical proposition than one that encouraged and sought to prepare people for a lifetime of learning and service to others and a commitment to the creation of a good, just, society.

- This essay is adapted from Stephanie Shaw,W. E. B. Du Bois and The Souls of Black Folk (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013). ↩

Powerful interpretation…thanks for sharing this knowledge. I embrace it.

I appreciate this insightful rereading of Du Bois’s Talented Tenth. As it so happened, my world history class today discussed Plato’s Republic. In a broader reference I made in that same class about Du Bois and black history month, I was able to connect the intellectual dots between Plato and how Du Bois drew on his reflections, and direct students to your essay. Thanks for your important work, and your timely reflections here.