Thinking About the ‘X’

As the year winds down, I find myself, like my AAIHS colleague Noelle Trent, reflecting on 2015, on conversations that might have fallen to the sidelines, or might be occurring just beyond the reach of black intellectual history.

Let’s talk about this ‘X.’

I’ve been trying to think may way into this post for some time. As a historian of slavery and as a media-maker who has been doing work around Afrxlatinidad for the last five years with the LatiNegrxs Project, I am often frustrated by ways scholars of Latinx and Latin American history avoid discussing histories of slavery and blackness in the Caribbean and South America. As an Afrxlatina/Latinegra with roots in Chicago, the U.S. South, and the island of Borinken, and a deep love for New Orleans and all of her fluid vernaculars, I find myself writing this while shifting between several languages in my head and heart—Puerto Rican Spanglish to American English to classic French to 90s hip hop interludes to #BlackTwitter shorthand to Academicese. The problem is language, written/digital languages at that, and the power of their power. Bear with me…

A post by two Swarthmore students has sparked some contentious conversation about whether scholars and activists, many of them queer or genderqueer, should use the term “Latinx.” At Latino Rebels, María R. Scharrón-Del Río and Alan A. Aja give a brief recent history of the debate:

“Earlier this year, Latina magazine (Reichard, 2015) headlined a short blog on the burgeoning term, as did the Columbia Spectator (Armus, 2015) in a longer report, both featuring quotes by scholars and activists who hailed its importance in disrupting the traditional gender binary and acknowledging the vast spectrum of gender and sexual identities. The social media popular Latino Rebels has published more pieces with usage of the term, including a recent thoughtful essay by Blanca E. Vega (2015), as are advocacy and academic conference programs incrementally evidencing its application.

Bueno/Perfect. Also:

Let’s get straight to the point then. Spanish is a primary marker of Latinx and Latin American identity. There is no reason to dispute this. But that marking didn’t occur without context.

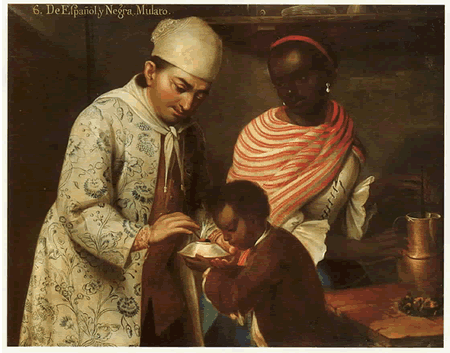

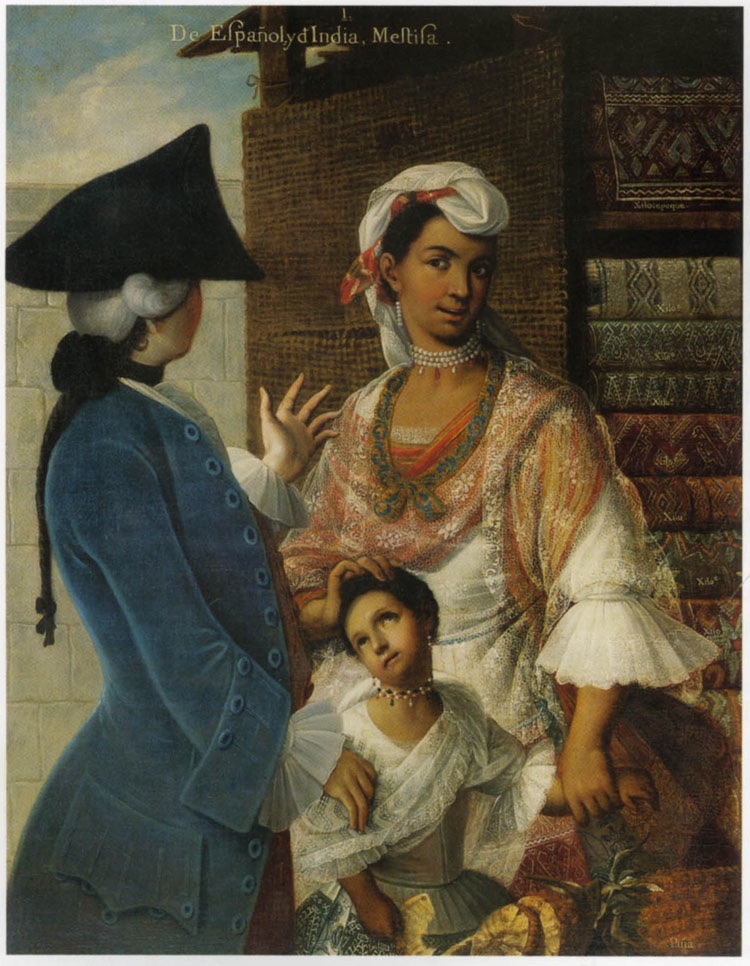

As many bloggers on this blog describe (and have spent their careers researching), as Afrxlatinx Studies has demonstrated, and as activists on the ground have demanded, Latinx and Latin American history is rife with the impact of slave trades, slavery, colonialism, and globalization. The countries that comprise the New World were created in the wake of massive profits generated by the trans-Atlantic and trans-oceanic circulation of silver, sugar, coffee, cotton and other products harvested and mined by black and indigenous laborers. One result (of many) was the marking of castas and mixed-race populations as non-citizens, subjects, exploitable labor, slaves, servants, and Other by Spanish and Spanish-identified (creole-born, blancos, even ‘lighter’ castas) imperial and ecclesiastical authorities, slaveowners, and landowners. These were the individuals with the everyday power to grant freedom, access to trades, professions, distribute land, offer safety, and spare lives. Their racial-marking expressed, imposed, and exposed the intersection of violence, coercion, and consent; it was embodied on the ground in intimate relations between and across race, status, and gender.

Post-emancipation and post-independence histories elaborate on this theme which is simply: There is a very dark and bloody black and indigenous history in Latin America, and while it is one which implicates the United States as an imperial power, the Spanish language was a symbol, product, and tool of violence within and against what became Latinx and Latin American populations well before the United States-as-empire comes into the picture.

In arguing against the ‘X,’ there seems to be more than a little bit of anxiety about playing fast and loose with language. What are we afraid will shake loose? Histories of vernacular destruction that trailed in the wake of slave ships? Native resistance that survived the destruction of sacred sites, forced labor, and dogs bred to tear flesh from bone? Latinxs’ problematic relationship to battling racism while playing model minority in our communities, schools, and workplaces? How, why, and what does it mean that our families run the phenotypical gamut from very dark to very light, the sexuality spectrum from straight to queer, but there does not yet seem to be a recognition outside of Afrxlatinx communities (academic, activist, and otherwise) that these are relations of power and violence, not a rainbow mezcla sin poder?

Visceral resistance to using the ‘X’ masks a deeper discomfort with who is included in the Latinx community and how far this inclusion may go. Whose history is centered and what does that mean for Latinxs’ relationship to power and empire when academics and activists are forced to step away from Spanish as either a magical unifier across varied Latinx experiences–or schema for distinguishing dark-skinned brown and black Latinxs as distinct from other people of African descent? What does it say about diaspora, community-formation, kinship? What also of the many ways Spanish has been a lingua franca joining black Latinx identities, a witnessing from within Afrxlatindad that says we are here, juntos, and won’t be rendered invisible.

Those of us who are queer Afrxlatinxs have been having this conversation and our work has been intersectional, futuristic, and insurgent. As Bianca Laureano noted over at The LatiNegrxs Project, even the Latino Rebels who argued for “intersectionality” in their discussion of the ‘X’ did a cartwheel over blackness and antiblackness—the very issues intersectionality, a theory and term coined by a black woman, was designed to address. Likewise, very few have dipped into this history of slavery and slave trading when debating whether or whether not to ‘X.’ What would happen if histories of black diasporic communities of Latin American descent and AfrxLatinxs in the United States (or abroad) were part of the discussion? Would they change the debate? The use of the X in communities of African descent has a history as political act and iconography, particularly in the second half of the 20th century. Incorporating this history into the debate has the potential to deepen the symbolic and historic power of the ‘X,’ so that even as it is used to break the gender binary it may also invoke an anti-racist intersectional paradigm that centers blackness and antiblackness within Latinidad. But not without doing the work.

It is also critical to invoke radical media and social media as praxis in this discussion. It should be of no surprise digital communities of queer, gender non-conforming, and transgender Latinxs (many of them Afrxlatinxs) have been using the ‘X’ for some time. In 2008, Twitter changed its platform so the arroba (@ symbol) when used in conjunction with another user’s Twitter handle (@jmjafrx) linked to the user. A ’swoosh’ icon followed, allowing users to easily reply/mention other users in conversation. Facebook made a similar change in 2009. As late as 2013, conversations online around how to use the arroba (@) symbol were still flourishing, but it was clear technical considerations had changed the ease and aesthetic pleasure with which the arroba could be used.

The use of the ‘X,’ in other words, has not occurred in a vacuum, isolated from the rise of digital communities of Afrxlatinxs, radical Afrxlatinxs, and LGBT Afrxlatinxs around the world who have sought out fresher and more evocative means of discourse, of reaching out and loving on each other. If there is something rich, creative, intersectional, coalitional, and radical about the ways language has changed with Latinx political imperatives over the last several years, it is steeped in changing media and the vibrant insistence of these social media communities search for safety and home.

Race, gender and sexuality within Latinidad, do not operate in silos, isolated from antiblackness, media, or even history. All live at the intersection of power, resistance, and violence. When debating using or not using the ‘X,’ the debate isn’t really about whether the Spanish language is sacrosanct, although the preoccupation with linguistic structure is a stubborn refusal to consider ways the masculine as a neutral form does a violence to queer, gender non-conforming, and transgender-identified Latinxs. The debate exemplifies the power colonial languages still have over who belongs and who does not, and the extent to which power is made and unmade by challenges from the ground–by users, on Tumblrs, in organizing workshops, in signs at protests, in journal articles and books, in archives, on blogs and in conversation. Certainly, the ‘X’ may not end up being the answer. If the ‘X’ has the same experience as the arroba, it may too shift and the identifier used to describe Latinxs may change again. There is no easy answer to the unmaking the New World, but anytime we decide to choose structure (even linguisitic structure) over real lives and bodies we are 1) expressing and describing a politics and 2) proving a point about the value and importance and precarity of those lives.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.