“The Rent Eats First”: Fighting Gentrification in California

A recent report found that the city I call home—Long Beach, California, located on the Pacific Ocean along the southern border of Los Angeles County, the second most populous city in the Los Angeles metropolitan area—ranked fifth among US cities with the fastest growing rent prices in the country. Given that the two-bedroom median rent of the four cities ahead of Long Beach on the list average roughly half that of Long Beach, the city may very well be California’s new epicenter of gentrification, which has already had devastating impacts on other cities like San Francisco, Oakland, and Los Angeles. As economic geographer Richard Walker notes, the scourge of gentrification is a “many-sided phenomenon” that combines the organic nature of cities themselves with urban growth, booming metropolitan economies, and increasing racial and economic inequality that create immense amounts of wealth for very few at the top while displacing large populations of folks, disproportionately black and brown, at the bottom.

Walker also highlights that chief among the drivers of gentrification is the role of government in supporting policies that prioritize the interests of corporations over those of lower-income residents of a given city. The alignment of corporations and governments is a hallmark of gentrification and neoliberalism more broadly. In California, the alliance of politicians with corporate interests—corporations, real estate developers, and landlords—reveals a state that has at best offered a half-hearted willingness to protect its most vulnerable residents and at worst encouraged the extraction of maximum economic profit through the displacement and gentrification of poor communities of color.

Causa Justa, “a multi-racial, grassroots organization building community leadership to achieve justice for low-income San Francisco and Oakland residents,” defines gentrification “as a profit-driven racial and class reconfiguration of urban, working-class and communities of color that have suffered from a history of disinvestment and abandonment. The process is characterized by declines in the number of low-income, people of color in neighborhoods that begin to cater to higher-income workers willing to pay higher rents.” Gentrification, therefore, brings together issues of housing, capitalism, and racial justice. With that in mind, it is important that we situate the more recent reality of gentrification within the larger history of producing wealth and poverty through housing policy. Which side of that divide one falls on has a whole lot to do with race.

A recent report, The Asset Value of Whiteness: Understanding the Racial Wealth Gap, found that the median white household has thirteen times the wealth of the median black household and more than ten times that of the median Latino family. While there are certainly a multitude of factors that contribute to this disparity, housing is a primary contributor. Gentrification is not only a matter of who has rightful claim to certain neighborhoods and city spaces, but it is also part of the much larger historical process of reinforcing white supremacy through housing policy.

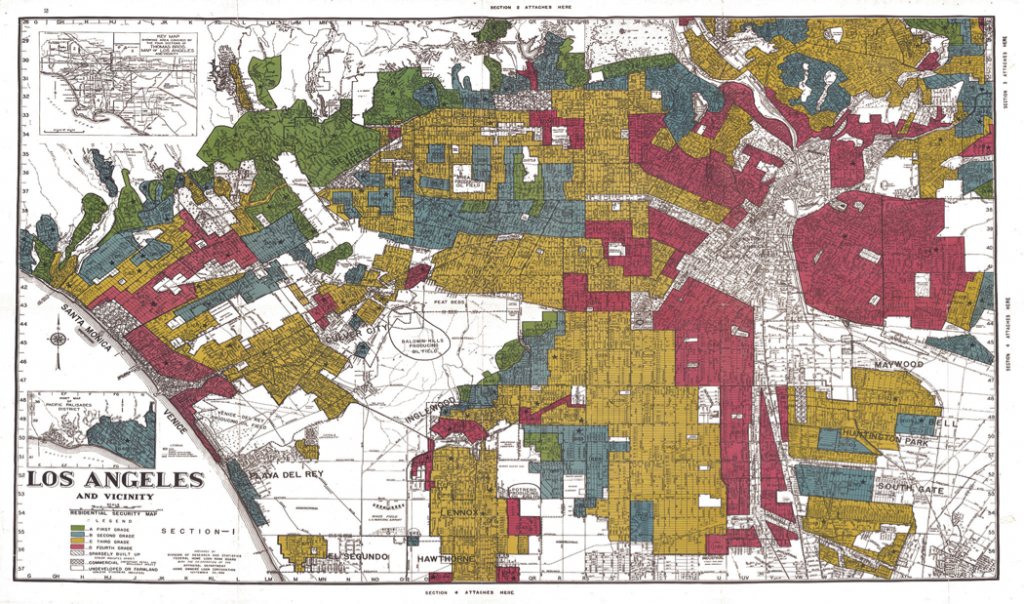

Redlining, for example, excluded communities of color and black communities, in particular, from the largest federal housing project in our nation’s history. That, combined with the restrictive housing covenants that white homeowners enacted to protect their investments via maintaining segregated neighborhoods, racialized the geography of the American city in new ways, creating what historian Eric Avila refers to as “vanilla suburbs” and “chocolate cities.” Housing projects like Cabrini Green in Chicago, Marcy in Brooklyn, and Jordan Downs in Watts (Los Angeles), built to deal with the subsequent overcrowding of those black and brown communities trapped by redlining, along with later developments like newly built freeways paid for by federal dollars that carved up neighborhoods like Boyle Heights in Los Angeles, produced even more blight. In other words, in the middle decades of the twentieth century, housing policy created a cycle that manufactured immense amounts of wealth and poverty. Whites got subsidized mortgages out in the suburbs and newly built freeways to better connect them to the downtown core; black and brown folks got redlining, housing projects, and federal interstates through their backyards. This history reveals the absurdity of contemporary partisan debates about “re-distribution” through tax policy. Contrary to the insistence of conservatives, the re-distribution of wealth occurs long before the levying of tax-bills.

Redlining was outlawed in 1968, but that did not eliminate the impoverishment of communities of color through housing policy. The sub-prime mortgage crisis, for example, catalyzed the 2008 housing collapse. While people of all races were victimized by the sub-prime mortgage collapse, blacks and Latinos were nearly two-and-a-half times more likely than whites to receive sub-prime loans. Much of the “why” in that case had little to do with economic inequality. In 2012, Wells Fargo paid $175 million to black lenders as part of a settlement with the Justice Department after the bank admitted that its brokers deliberately steered black and Latino borrowers into sub-prime loans in order to maximize lender fees, even though those customers qualified for prime loans.

So, whether it’s government policy or private banks, a (relatively) regulated Keynesian economy or a deregulated neoliberal one, blacks and Latinos have not only repeatedly been denied access to wealth accumulation through homeownership, but housing policy has continually impoverished the communities in which they live. In this context, gentrification offers a more recent episode in our nation’s much longer narrative of manufacturing wealth and poverty through housing policy. Gentrification, moreover, embodies the relationship between government and the market in the age of neoliberalism. Neoliberalism, in theory, posits maximizing economic efficiency by implementing, wherever possible, markets and market-logic in order to reduce the wasteful inefficiency of the public sector. However, it is not, as some argue, anti-statist. Neoliberalism, according to political economist Jamie Peck, “has always been about the capture and reuse of the state in the interests of shaping a pro-corporate, freer trading ‘market order’.” Gentrification provides an illuminating case study in the ways in which neoliberalism has not sought to eliminate, but instead to capture and re-task the state to serve pro-corporate interests.

San Francisco, perhaps the nation’s most gentrified city, offers a case in point. In 2012, the city passed Proposition E, a massive tax cut for any corporation that moved into office buildings in San Francisco’s mid-Market district, at the encouragement of Mayor Ed Lee. Dubbed the “Twitter Tax Break,” in 2014 alone Prop E. equated to a $34 million tax cut for tech companies. The recruitment of tech companies through government handouts has led to a massive influx of high-earning tech workers into San Francisco neighborhoods like the Mission. This influx has pushed the average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in the city over $3100 per month, which is displacing the Mission’s longstanding working-class Latino population. While one might hope “techies” and the corporations that employ them cared more about the populations they are forcing out, it is ultimately the responsibility of City Hall to protect the city’s residents. Yet, the routine prioritization by the San Francisco government of corporate interests over those of lower-income residents illuminates the political displacement of people by corporations in the neoliberal era.

Long Beach appears headed down a similar path, but the lack of tenants’ rights here makes poor and working-class communities of color more vulnerable to the draconian displacement that has already devastated San Francisco’s Mission District. Long Beach is the largest community of renters on the West Coast without any form of rent control or just cause eviction rights for tenants. A landlord can increase a tenant’s rent by any amount or send an eviction notice at any point with little notice and without cause. As Josh Butler, Executive Director of Housing Long Beach, a non-profit organization founded in 2011 that advocates for more affordable housing and tenants’ rights in our city, explained, “The lack of tenants’ rights, combined with the city’s old downtown core, its high population of renters, high-poverty rate, and low-vacancy rate make it a perfect target for gentrification.”

Gentrification reveals a deeper, more historically rooted discourse of race, home ownership, and citizenship. Government policy has, for the last 80 or so years, proved incredibly effective at creating wealth and poverty through housing policy. Race has fundamentally determined on which side of that divide one falls. The gentrification of cities like San Francisco and Long Beach reveals the ways local governments often prioritize the interests of corporations over those of their low-income black and brown residents. Resisting gentrification therefore demands a two-pronged approach. On the one hand, cities need strong tenants’ rights and an adequate affordable housing stock to protect their renters from displacement. On the other hand, we need a more critical engagement not simply with the racial politics of who profits and who is victimized by gentrification, but how those racial dynamics have inhibited our collective willingness to ease the burden of gentrification and displacement. As Butler told me about his organization’s efforts, “Until recently whites haven’t been impacted at the same rate as people of color, so we’ll see what happens, but I suspect if Housing Long Beach was organizing all white renters this problem would’ve already been solved.”

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.