“Scholarship is Not Dispassionate, But it is Deliberate and Systematic”: Robin D. G. Kelley Reflects on Cedric Robinson

Today we conclude our special series in honor of Professor Cedric Robinson who passed away on Sunday, June 5, 2016. Dr. Robinson was a beloved scholar and mentor who authored several foundational texts including Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition and Terms of Order: Political Science and the Myth of Leadership and Black Movements in America. Over the past few days we featured reflections from David J. Leonard, Josh Myers, Minkah Makalani, Cara Moyer-Duncan and Stephen G. Hall.

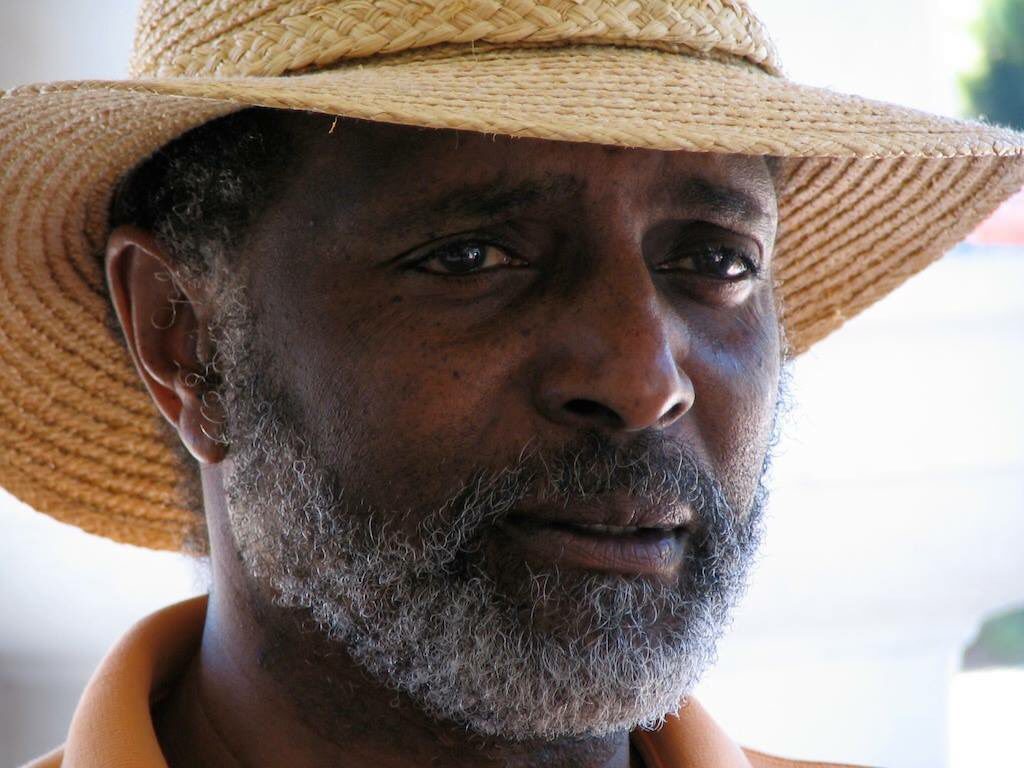

In this final post, Dr. Robin D.G. Kelley reflects on the influence Robinson had on his research, and emphasizes Robinson’s unwavering commitment to mentoring.

***

Many colleagues are taken aback when I tell them that a political scientist taught me how to be an historian. Although this isn’t entirely accurate since Cedric Robinson was no ordinary political scientist—his Stanford University doctoral dissertation, “Leadership: A Mythic Paradigm” (1975), was essentially a critique of his discipline.[i] His work has had a profound impact in the fields of Sociology, Anthropology, Political Economy, Film Studies, Cultural Studies, African and African Diaspora Studies, and of course, History. No discipline could contain him. No geography or era was beyond his reach; he was equally adept at discussing Ancient Greece, England’s Middle Ages, or early anticolonial rebellions in Southern Africa.

But rather than discuss his scholarship, I want to say something about his extraordinary role as a mentor. In 1984, he agreed to serve on my exams and dissertation committee after I cornered him at a meeting of the African Studies Association in Los Angeles. He readily agreed and I began a regular trek from UCLA to UC Santa Barbara about every other week to meet with him. When I mustered the courage to send him an early draft of an essay on African Americans in the Communist Party, he sent back three single-spaced pages of humbling criticism in the form of a letter dated June 21, 1985. After taking me to task for “haphazardly” treating the historiography, he advised me to “temper your literary voice” and stop editorializing. Of course, I was trying to write like C. L. R. James, W. E. B. Du Bois, Walter Rodney, and Karl Marx, full of sly humor and sarcastic digs at the ruling classes. Cedric wasn’t impressed: “From what little I know of the profession and particularly the department at UCLA, neither sarcasm nor direct political charges will be tolerated by almost any reviewing committee you might construct. Save your judgments for the published version of your work not the dissertation. Scholarship is not dispassionate, but it is deliberate and systematic in the way it reconstructs an event. Try not to indict for racism when the materials will allow you to ‘discover’ it.” Sage advice, to be sure; I’ve spent three decades repeating his words to my own students.

Cedric demanded that I pay more attention to political economy, to the various racial, ethnic and national struggles taking place within the Communist Party, to its deep distrust of “petit-bourgeois nationalism,” and to why the Party seemed vulnerable to the kind of vulgar Marxism that substitutes “economism. . . for historical analysis” and takes the revolutionary force of the proletariat as an act of faith. He listed many reasons why he thought this was the case—from the canonization of the Bolshevik Revolution to the fact that bourgeois nationalism defeated or undermined radical movements in Western Europe, leaving fascism and national imperialism in its wake. But the explanation that floored me was Cedric’s almost off-hand remark that the largely foreign-born radical intelligentsia that dominated the Party knew very little about U.S. history and was unaware that “the South had been the intellectual vanguard of American society, and as Du Bois had demonstrated in Black Reconstruction, Black workers had led many of the radical movements before the 1870s.” Communists could not have known this, he added, since the Party did not have theoreticians of the caliber of Oliver Cox, Du Bois, James, Frantz Fanon, or Amilcar Cabral.

Cedric kicked my ass 31 years ago. He continued to kick my ass, lovingly but relentlessly pushing me to be the historian I’m still trying to become. This is why I cherish that letter, and why I love Cedric J. Robinson.

[1] He published a slightly revised version of the dissertation titled, The Terms of Order: Political Science and the Myth of Leadership (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1980)

Author and historian Robin D.G. Kelley is one of the most distinguished experts on African American studies and a celebrated professor who has lectured at some of America’s highest learning institutions. He is currently the Gary B. Nash Endowed Chair of U.S. History and Professor of Black Studies at UCLA. His research explores the history of social movements in the U.S., the African Diaspora, and Africa; black intellectuals; music; visual culture; contemporary urban studies; historiography and historical theory; poverty studies and ethnography; colonialism/imperialism; organized labor; constructions of race; Surrealism, Marxism, nationalism, among other things. Kelley’s work includes several foundational books including Race Rebels: Culture, Politics and the Black Working Class; Yo’ Mama’s DisFunktional!: Fighting the Culture Wars in Urban America; and Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination. His essays have appeared in a wide variety of professional journals as well as general publications, including the Journal of American History, American Historical Review, Black Music Research Journal, African Studies Review, New York Times (Arts and Leisure), New York Times Magazine, The Crisis, The Nation, The Voice Literary Supplement, Utne Reader, New Labor Forum, Counterpunch, to name a few.

Author and historian Robin D.G. Kelley is one of the most distinguished experts on African American studies and a celebrated professor who has lectured at some of America’s highest learning institutions. He is currently the Gary B. Nash Endowed Chair of U.S. History and Professor of Black Studies at UCLA. His research explores the history of social movements in the U.S., the African Diaspora, and Africa; black intellectuals; music; visual culture; contemporary urban studies; historiography and historical theory; poverty studies and ethnography; colonialism/imperialism; organized labor; constructions of race; Surrealism, Marxism, nationalism, among other things. Kelley’s work includes several foundational books including Race Rebels: Culture, Politics and the Black Working Class; Yo’ Mama’s DisFunktional!: Fighting the Culture Wars in Urban America; and Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination. His essays have appeared in a wide variety of professional journals as well as general publications, including the Journal of American History, American Historical Review, Black Music Research Journal, African Studies Review, New York Times (Arts and Leisure), New York Times Magazine, The Crisis, The Nation, The Voice Literary Supplement, Utne Reader, New Labor Forum, Counterpunch, to name a few.

Thank you, Robin, for your tribute. This was my experience too. And I trust our students who read your words will understand that we expect no less of them than Cedric Robinson expected of us, even if we can’t hold a candle to our mentor and friend.

And for the curious: UNC Press has republished The Terms of Order, with a terrific foreword by Erica Edwards.

http://uncpress.unc.edu/browse/book_detail?title_id=3762

Thank you, Robin.

Thavolia

To All who have written so eloquently about Cedric, I can only say that a week ago I had not heard of AAIHS (thanks, Joel Samoff for correcting that). But each of your comments has assured me that Cedric’s work will carry on. In his published work he was always trying to provide readers with access to libraries that they did not have, to demonstrate how much can actually be found in the historical record if one bothers to search, that even when the intent has been to bury or erase the very existence of so many the half life provides for careful excavation and rediscovery. To you all – writers and readers – I say carry on! And thank you.

Sincerely

Elizabeth Peters Robinson