Reflections on Race, Diaspora, and Nation

“People of African descent, wherever they reside, should always be mindful that national struggles can never be disentangled from diasporic ones.”

This summer I had an encounter in Fortaleza, Brazil, which has become a second home for me. I have been traveling and living there for close to twenty-five years. On this particular day, I was speaking with my friend who is a professor at the State University of Ceará in Brazil. We drank beer and ate our lunch among a group of friends at a French restaurant called Le Marche in front of the old market place called Mercado Pinhoes.

The subject of race came up and my friend did not appreciate what I was saying: she told me in her provocative way to reread Gilberto Freyre’s The Masters and the Slaves, a classic but outdated text on understanding the uniqueness of Brazilian “race relations.” She was afraid that I was collapsing the history of Brazilian understandings of Blackness and American understandings of Blackness.

She insisted on the idea of Brazilian racial exceptionalism—that Brazil is virtually free of American style racism because of its history of extensive “racial intermixture.” I did not dispute that Brazil was a country with a unique historical experience separate from the United States. My suggestion to her and intellectuals of all national identities is to stop only articulating the meaning of race within a limited national context. We need not abandon the reality of the nation-state, but we need to take the intersections of race, diaspora, and nation more seriously.

My friend is a woman of color and she was not denying the legacy of racism in Brazil, but she seemed unwilling to recognize the ways race intersects with the nation-state throughout the diaspora. Her apprehension was in part the idea that people of African ancestry could be part of a transnational diaspora.

She assumed that the discussion of Blackness was a North-American way of thinking—one that was being imposed on Brazilians. After all, if Brazil was a place of racial mixing, how could Brazil be like the United States?

I understand my friend’s desire not to conflate a kind of American Blackness—particularly if that means engaging in some universal way of being black. I agreed that we must avoid the bias of viewing the experience of Blackness in the United States as holding any authentic way of being black. However, must we simplify our realities to one of the nation-state experience or the African Diaspora? I think it is far more useful to contextualize Blackness from a global perspective.

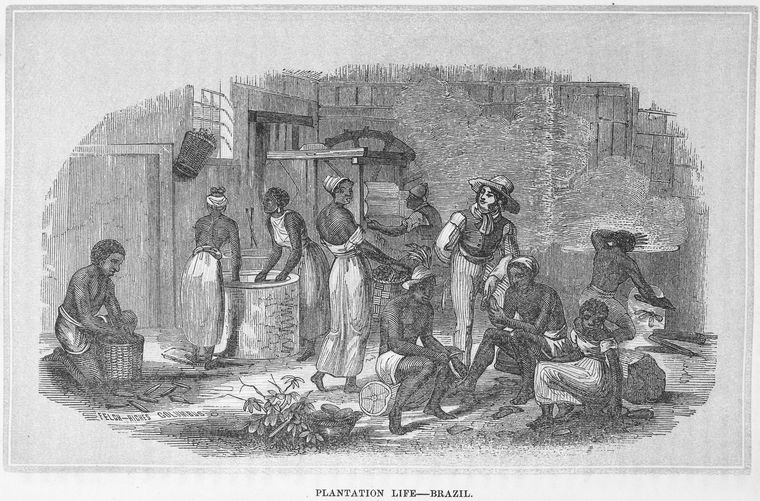

The history of slavery in the Americas is a fact, and its aftermath of anti-black attitudes is also a fact. There is nowhere you can go in the new world and not see people of African ancestry disproportionately at the bottom of the socio-economic pyramid. Even in Latin America where there was supposedly minimal racial discrimination scholars like Edward Telles have documented what he calls ethnoracial inequality. If this is indeed true, why do we still often-marginalize comparative research of the history and sociological conditions of the people of the African diaspora? In the last twenty years, we have had made enormous progress, but scholars and activists in general still need to consider more seriously the voices of Afro-Diasporic activist-intellectuals.

For example, Brazil has a history of Afro-Brazilian civil rights organizations mobilizing against racism and oppression for centuries. During the 1970s, for example, the Movimento Negro Unificado (MNU) arose in Brazil and the organization emphasized transnational approaches. Leaders such as Lelia Gonzalez and Abdias do Nascimento maintained a diasporic vision without overlooking national concerns. They were in solidarity with Africans and the African diaspora. The political organizing of Afro-Brazilians in the 1970s has brought enormous consciousness and changes that have combated anti-black attitudes in Brazil.

These earlier movements underscore the significance of black internationalism, which has informed struggles for liberation since the Age of Revolution. The Haitian Revolution, for example, served to inspire people of African descent throughout the Americas and represented a model for black liberation based on ensuring equality for all people of African ancestry. These transnational currents would be evident in black power movements in the United States, Brazil, and across the globe. It is ahistorical, then, to overlook the many Afro-diasporic modes of expressions that have shaped black political thought and praxis for centuries.

As I reminded my Brazilian friend, anti-black attitudes existed throughout the African diaspora and certainly did not escape Brazil. The overlapping histories of slavery, racial regimes, and de jure and de facto segregation in Brazil as in other nation-states underscore this point. We must reckon with the different points of positionality in the Americas—we speak different languages and share different national histories—but this does not preclude essential points of commonalities. People of African descent, wherever they reside, should always be mindful that national struggles can never be disentangled from diasporic ones.

Tshombe Miles is Assistant Professor of Black and Latino Studies at Baruch College and studies the history of Latin American race and ethnicity as well as the black diaspora in the Atlantic World. He is currently researching the fight against slavery and freedom in 19th Century Brazil. He is the author of A luta contra a escravidão eo racismo no Ceará, Brasil (The Fight Against Slavery and Racism in Ceará). He earned a BA from City College of New York and a PhD from Brown University. Follow him on Twitter @DrTLee.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

“People of African descent, wherever they reside, should always be mindful that national struggles can never be disentangled from diasporic ones.” I am not sure i comprehend this fully as stated. Shouldn’t this read as * “People of African descent, wherever they reside, should always be mindful of the international struggles rather than the dispora. I mean what political importance does the trans atlantic dispora now have on migration policy? I can easily see the Palestinians, Iraqi, diasporas have increasingly become significant players in the international political arena. The aforementioned regard their diasporas as strategically vital political assets. Other dispora groups such as India, the Philippines, and other migrant-sending countries, have been recognizing the massive contributions their diasporas make through remittances.Most self-described diasporas do not emphasize the melancholy aspects long associated with the classic Jewish, African, or Armenian diasporas. Rather, they celebrate a culturally creative, socially dynamic, and often romantic meaning.The Diaspora is very special to India. Residing in distant lands, its members have succeeded spectacularly in their chosen professions by dint of their single-minded dedication and hard work. What is more, they have retained their emotional, cultural and spiritual links with the country of their origin. This strikes a reciprocal chord in the hearts of people of India and rightfully so. In Black America the dispora is symbolic we have Kwanzaa The celebration honors African heritage in African-American culture, and has also spread to Canada, and is celebrated by Black Canadians in a similar fashion as in the United States it gives nothing back to the mother country, it is our struggle for equality in the assimilation of America as a melting pot or tossed salad however fitting. The international struggle imho remains equality. I apologize for being so wordy the blog was good food for thought and stimulated some juices. One Love!