African American Freedom and the Illusive “Forty Acres and a Mule”

On August 18, 2016, the United Nations Working Group on Experts of People of African Descent determined that the history of Black people’s enslavement in the United States justifies reparations for centuries of forced labor and racial terror. According to the Working Group, reparations could come in a variety of forms including an apology, health initiatives, debt cancellation, and financial support. Conterminously, Duke University economics professor William Darity has determined that monetary reparations for African Americans in the twenty-first century would amount to 1-6 trillion dollars

One-hundred and fifty-two years ago, reparations for Black Americans were tepidly attempted by the federal government on January 16, 1865. After completing his march to the Georgia coast, General William T. Sherman issued Gen. Field Order No. 15, which reserved the Sea Islands and abandoned inland rice fields in coastal South Carolina, Georgia, and northern Florida for the ownership and occupancy of formerly enslaved Black Americans. Under Sherman’s order, Black men and women, who were heads of their household, received from five to forty acres of “abandoned land.” The Freedmen’s Bureau, established in March 1865, was charged with ensuring that these provisions were implemented.

When President Andrew Johnson reversed the Order in early Spring 1865, formerly enslaved Black Americans in Georgia and other parts of the South still held on to the belief that the federal government would eventually honor their word and provide them forty acres of land and a mule as some sort of quantifiable and measurable compensation for enduring the oppression of American enslavement. The promise of forty acres and a mule died slow for former slaves and became embedded in the historical memory of their descendants through stories passed down within the Black community.

In her early assessment of land redistribution and Black wealth, Lawanda Cox contends that land distribution would have had a negligible effect on alleviating African American poverty. However, Paul Cimbala has implied that only confiscation and land distribution would have guaranteed the freedom and well-being of former slaves. Historians must move beyond counterfactual analysis by examining the community-building actions African Americans initiated to secured land and achieve intra-racial autonomy in the absence of federal programs and lost opportunities. Federal land policies did fail; and opportunities to advance the material well-being of former slaves were lost; how then can historians reconceptualize the story of African American freedom? Local analyses that consider temporal and spatial distinctions provide the clearest window through which we can understand the achievements and aspirations of African Americans. Moreover, local histories of Black communities provide greater insights into the ways in which formerly enslaved men and women achieved economic and social freedom in spite of not receiving their promised forty acres.

African Americans who received land under Sherman’s Field Order and who formed the all Black town of Burroughs, Georgia illustrate the ways in which Black people claimed their freedom in the absence of federal land policies. As economic and social oppression intensified in the late nineteenth century, the Burroughs community made a strong bid for their economic and social independence within the protective intra-racial confines of an all-Black community. In challenging their marginal status and building political coalitions in response to state disfranchisement, the community became the only incorporated Black town in Georgia in 1898. The town’s community building initiatives included the establishment of churches, businesses, Masonic lodges, and mutual aid and benevolent associations. Although Burroughs was a farming community, its population included skilled trades people and artisans.

There were as many as 200 similarly self-sufficient intra-racial Black American towns during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. As Eric Foner aptly concludes, the autonomy offered by land ownership, which provided the foundation for these communities, was “defensive rather than the springboard for sustained economic advancement.” 1 Land ownership shielded African Americans from the worst aspects of economic exploitation, however, the prospects for sustained economic development were limited without access to capital and credit.

Andrew Johnson’s abrogation of the promise of “forty acres and a mule” inured African Americans to seek other means to secure land and economic independence in the South. The residents of Burroughs, Georgia accumulated the resources to purchase land and other forms of property through the region’s rural-urban economy. In some cases, pre-Civil War opportunities to accumulate cash and property had existed which placed freed men and women in a better position to acquire land. The formation of the town of Burroughs represented the apogee of African American resistance to political, economic, and social injustice. The town’s Charter of Incorporation in 1898 advanced the turn of the century principles of self-help, moral uplift, and racial solidarity through its governing body. Both the struggle and acquisition of land knit families and communities together. Some families had enough resources to pool them together passing on acquired land from one generation to the next. Few other rural communities in Georgia or elsewhere in the South enjoyed such amenities. In most plantation areas, sharecroppers had comparatively little control over their labor, their dwellings, or the future.

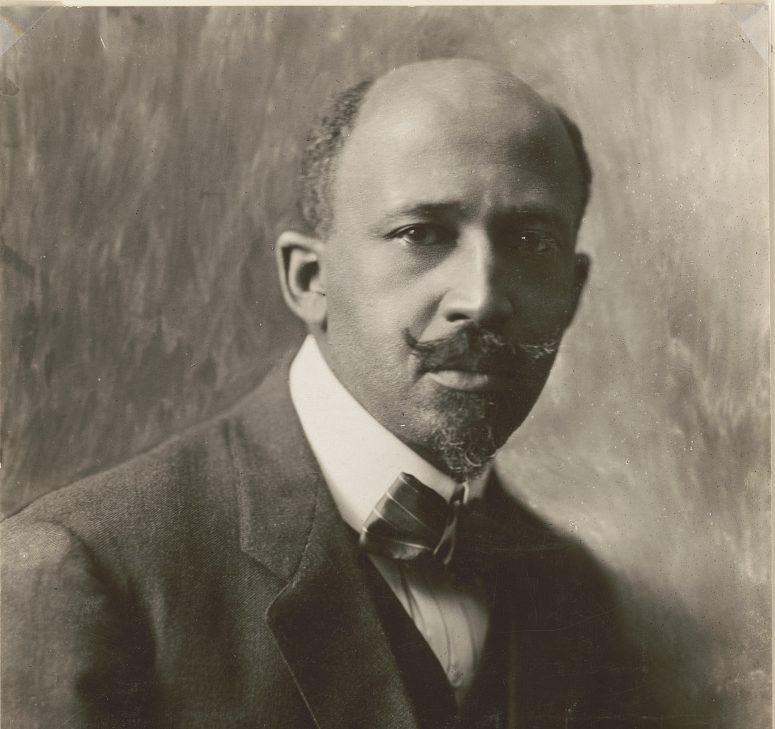

During the first decade of the twentieth century, renowned historian, sociologist and civil rights activist W.E.B. DuBois traveled extensively to assess the historical and contemporary problems facing African Americans. He surveyed Dougherty County, which encompasses Albany, Georgia, and published his findings in The Souls of Black Folk; and he studied Black land ownership in coastal Georgia for the U.S. Labor Department in 1901. These two research reports illuminate some regional experiences of African Americans in the post-Civil War South and Reconstruction’s legacy. With a population of one million, Georgia was home to more Black Americans than any other state at the turn of the twentieth century. For Du Bois, one needed to only travel to Dougherty County to understand the race question in America. It was here that 80 percent of the Black population worked the same land they had once worked as slaves; where 66 percent of the Black population remained illiterate; and where slavery continued under a new form of capitalism. Conversely, in coastal Georgia, according to DuBois, freed men and women united and purchased land, holding 56,000 acres by 1909. 2

Nearly a decade earlier, Booker T. Washington in his “Atlanta Compromise” speech articulated a philosophy of separation and accommodation as the best strategy for Black advancement, which influenced the Black town movement in the South. The most prominent Black American town influenced by Booker T. Washington was Mound Bayou in the Mississippi Delta. Mound Bayou existed as an imperium in imperio a sovereignty within a sovereignty, which embraced the principles of economic advancement, racial solidarity, and self-help.

In this context, the approaches used by historians to examine the economic plight of African Americans in the postwar South fall into four categories: economic politics, market analysis, racial exploitation and more recently property ownership. In the context of market analysis, Stephen DeCanio’s Agriculture in the Postbellum South and Robert Higgs, Competition and Coercion contend that despite violence and intimidation from native white southerners, African Americans made strident economic gains. “Their initial per capita income rose by 2.7 percent and their housing, diet, living standards, and material wealth rose significantly. Moreover, their real property ownership also increased.” 3

Comparatively, Roger L. Ransom and Richard Sutch developed a more cautious model of analysis. In their study One Kind of Freedom, Ransom and Sutch argue that the gains made by African Americans should be measured against the reality that they were “under constant attack by a dominant white society determined to preserve racial inequalities.” They argue further that “the economic institutions established in the postwar South effectively operated to keep former slaves as a landless agricultural labor force.” 4

The theme of racial exploitation is a topic expanded upon by scholars Johnathan Wiener and Jay R. Mandle. Labor historian William Cohen also views the post-emancipation era as exploitative in that it created a new kind of slavery through the sharecropping system, the institutionalization of the crop-lien system, convict-leasing, and the monopoly held by planters. While there is some truth to the interpretations of each of these scholars, they do not represent the full spectrum of the lived experiences of African Americans in the post-emancipation period.

Loren Schweninger has argued that understanding Black economic reconstruction requires a systematic analysis of Black property ownership in the South before, during, and after the Civil War. In his seminal study Black Property Owners in the South, Schweninger demonstrates through state by state analysis the divergence in the African American experience and the diversity of regional growth and development in the Lower South. He cogently demonstrates that even in the hostile climate of the late nineteenth century, former slaves were able to achieve property owning status.

The development of African American towns in the South represented a significant counterpoint in the story of African American freedom at the turn of the twentieth century. The existence of African American towns in the South depended on the extent to which African Americans could acquire land, exert control over their economic resources, and live free from land seizures by white southerners. It was not easy. In 1923, the majority Black town of Rosewood, Florida was destroyed by white mobs after a white woman falsely accused a Black male of assaulting her. In 1994, the Florida legislature passed a bill providing $150,000 in reparations to the Rosewood victims for loss of property. The Rosewood bill was the nation’s first compensation bill for African Americans who suffered racial injustice.

African Americans managed to accumulate 15 million acres of land by dint of their own initiative during the post-emancipation years. Reparations are over a century overdue and the political prospects are dim for translating “forty acres and a mule” into tangible compensation for a history of slavery and racial terror.

- Foner, Eric, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, (New York: Harper and Row, 1988) 109. ↩

- DuBois, W.E.B., “Georgia Negroes and Their Fifty Million of Savings,” The World’s Work 18 (May 1909): 11552; DuBois, “The Negro Landholder of Georgia,” Department of Labor Bulletin no. 35 (July 1901): 735. ↩

- Anderson, Eric and Alfred Moss, Jr., The Facts of Reconstruction: Essays in Honor of John Hope Franklin, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1991)172. ↩

- Ibid. Ransom, Roger L. and Richard Sutch, One Kind of Freedom: Emancipation and Its Legacy (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1977) 198. ↩

Fascinating article, thank you. The wealth, the entire wealth of the USA today rests on expropriation, genocide of native peoples, the capital accumulation achieved through slavery and the exploitation of working class, often immigrant, labor. Terror was a tactic in varying degrees used against all of these people, especially African Americans.

Since the time of the enclosures during the transition from feudalism to capitalism property has been, rightly, viewed as a means, especially for poorer people, to achieve a degree of independence. That people just out of slavery were able to do it in the face of ongoing terror and repression is nothing short of amazing and a tribute to their grit.

I would like to add that it was not simply “white repression” but white *capitalist* repression. For this was the period in which it became of vital importance to the ruling class to foment and maintain racism. It was perhaps their greatest fear that the white working class and African Americans would unite their common interests to overthrow them. (African Americans were, at that time, by definition working class.)

Of course they also quickly realized that black workers in a racially divided system could become the cushion for their fluctuating employment needs, “last hired, first fired.”

Thank you. I concur that white capitalist repression was responsible for fomenting and maintaining racism and class divisions. Your comments are insightful!

Wonderful article, Karen. You might be interested in viewing an interesting letter we uncovered which is displayed on our website at: AfricanAmericanCollection.com/images/reconstruction. See “Promises, Promises: The Enduring Legend of Forty Acres and a Mule.”

Kit Southall

Sr. Curator,

Mark E. Mitchell Collection of African American History

Thank you for the link Kit!