Visualizing Music: Representing Black Culture, Community, and Politics

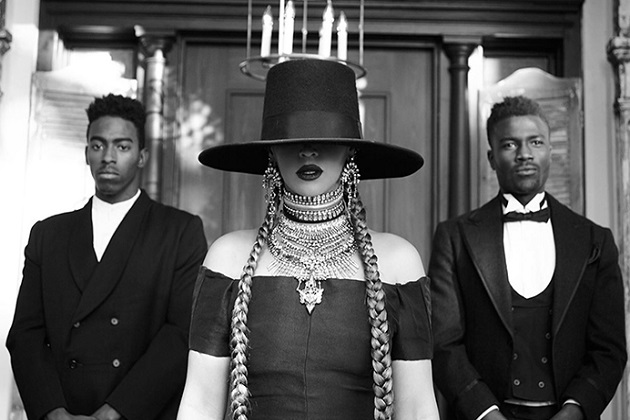

Figure 1

As Jessica Marie Johnson has already documented here on AAIHS, black women utilized Beyoncé’s song, video, and performance of “Formation” (Fig. 1) to engage in intellectual histories while publicly debating the ways that black women’s texts reflect politics, cultural memories, and racial and sexual identities. Part of that intellectual engagement is the recognition of a legacy of bringing black music to life. Indeed, our black musicians have been so genius at this, so “universal” in the way that their art transcends and crosses borders across the globe (compared to other art forms, such as literature, visual art, film and theater) that Black Arts Movement proponents like Larry Neal used to lament that our writers were not as adept as our musicians.

For black women popular music artists in particular, who have the double burden of race and gender, their musical labors are often reduced in the industry to 1) backup singers (as the documentary feature 20 Feet from Stardom explores), 2) video girls, or 3) stylized singers, whose genius is always undercut by the gendered distinction of “divas.” However, in a strategic move, Beyoncé appropriates a blonde and white femininity that her lighter-skinned embodiment could assimilate to launch the aesthetics of black vocal styles, black musicality, black lingo, and black fashions toward a global audience. That “Formation” represents her most in-your-face articulation of black politics, which disturbed the interracial public sphere, illustrates how Beyoncé has been quietly revolutionizing the spaces allotted to black music and culture. I dare say: the spirits of Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, Michael Jackson, and Whitney Houston are all whooping and hollering and now dancing “in formation.”

Having already written on the aesthetics and politicized narratives of “Formation,” I am now interested here in highlighting a genealogy of visualizing black music that situates Beyoncé in a wider historical context. For it was not lost on me how, during the Superbowl halftime performance, that while her backup dancers saluted the Black Panthers through style and raised fists, the pop star herself chose to signify the king of pop, Michael Jackson, by donning a jacket similar to the one he wore during his own halftime performance back in 1993 (Fig. 2). Such signifying gestures towards Beyoncé’s own ambitions to emulate the superstardom status of MJ, but they also remind us of the politics of the music video as an important slice of life in re-presenting the black body by reaffirming everyday black life, struggles, and always, our dreams and fantasies. That, in a year of #OscarsSoWhite, in which black representation in Hollywood cinema is woefully underrepresented, the Music Video serves as powerful counter-narrative.

Figure 2

Just before Beyoncé created controversy with her latest video and performance, Spike Lee’s documentary on Michael Jackson’s influential 1979 album, Off the Wall, screened on the premium cable channel Showtime. Offering insight into Jackson’s plans for his later world domination through music, as well as his insistence on breaking through the white-dominated music industry when this album only won R&B awards at the Grammys, we can appreciate how his later global success with his subsequent game-changing album Thriller had everything to do with visualizing black music – and thus transcending its R&B/funk categorization – through the Music Video.

I remember the first time I had a chance to watch MTV on the cable TV at my babysitter’s house when I was around 9 or 10 years old. I was able to watch my very first music video in the company of my babysitter’s six children, two of whom were around my age and who became my regular playmates. We were all just in complete awe when we saw Michael Jackson’s Billie Jean air. Without realizing the racial breakthrough Jackson made on a TV station like MTV, which up until that time focused almost exclusively on rock music, we were just glued to the TV set and imagined that we were watching a magician in his high-water pants and saddle shoes, whose every step and touch shed light and made the world a better place. Every dance move seemed mind-blowingly out of this world. And this was even before he unleashed his moonwalk onto the world.

This pop icon was already legend. And it didn’t matter, after watching that video, whether we understood the lyrics to the song. With “Billie Jean,” we not only heard the song, we saw the song.

Historically, Hollywood cinema marginalized black people (especially when attempting to market their films in the Jim Crow South). As such, they were given to creating musical shorts featuring African American music and life, which could later be edited out for white segregated audiences. Bessie Smith in the 1929 St. Louis Blues embodies a pathetic, lovelorn and exploited woman, but her blues and the accompaniment of the chorus, set in a local bar, would inform the soundtrack of 1930s films, especially in highlighting sexually transgressive white women (Stanfield 2002). The musical short featuring Duke Ellington’s Symphony in Black (1935) portrays the black musician at work and conjuring images of black life through different musical themes. Featuring a young 20-year-old Billie Holiday, whose lovelorn blues woman is spliced alongside a trombonist, Holiday is thus illuminated for her virtuosity and her musicality. And in the movie musical Stormy Weather (1943), featuring a black cast, Katherine Dunham’s “Stormy Weather” choreography literally transcends the movie narrative when it shifts from a street scene to a mythical and otherworldly plane (Fig. 3).

Figure 3

Michael Jackson utilized the visual aesthetics and narratives from Hollywood to inform the music videos of songs like “Beat It” (think West Side Story, except involving the Bloods and the Crips), “Thriller” (think Romero’s Night of the Living Dead), and “Smooth Criminal” (its throwback to film noire gangster films). What Jackson did was make a more legible space for black bodies and black aesthetics, and especially for black politics, which his sister and pop star Janet Jackson perfected with her 1989 anti-racism anthem video for “Rhythm Nation” (a definite influence and precursor to Beyoncé’s “Formation.”) Such politics further exploded in the hip-hop genre, which took even longer to break through on MTV (hence, why BET created a space for African American music and life). Public Enemy’s Spike-Lee-directed “Fight the Power” (1989) opened up space for political representation and the aesthetic of “around the hood” imagery that these artists supposedly represent (Brooklyn in PE’s case), while rappers like Queen Latifah signified politically on feminism in global (Ladies First – 1989) and local (UNITY – 1993 ) contexts.

Figure 4

These regional politics of signifying the neighborhood and the affirmation of blackness, Latinidad, and/or other subalterns (from Lauryn Hill’s “Doo Wop (That Thing)” [Fig. 4] to Lil’ Kim’s “Lighters Up” to M.I.A.’s “Paper Planes“), as well as the disruptive aesthetics and embodiment that rapper Missy Elliott constantly presented in the public sphere ever since her goundbreaking “The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly)” video (1997) all serve as foundational texts on which Beyoncé’s “Formation” is built. Not only do these precursors help to inform how to visualize black music alongside regional versus global identities (whose regionalism, incidentally, translates across borders when global hip-hop artists constantly invoke local identities – from Palestine to Cuba – while remixing transnational sonalities), but they also constantly present the tensions of pop stars who must navigate between their one-percent status as wealthy entertainers while their livelihoods are quite dependent on cultural, political, and economic support of the 99-percenters, especially when their public personas are carved out of a “sense of belonging” to particular neighborhoods and communities.

Figure 5

Beyoncé’s visual album BEYONCÉ constantly reflected these tensions, but “Formation” grapples with a community and larger society shaken by state violence and the movement of resistance represented by #BlackLivesMatter, which she and her partner Jay Z have supported financially. Nonetheless, her video does not signify on images of violence, represented in recent videos like Nicki Minaj’s “self-defense” track for “Looking Ass” (Fig. 5), Kendrick Lamar’s denouncement of urban violence in “Alright,” or Rihanna’s revenge fantasy in “Bitch Better Have My Money.” The main elements of violence in “Formation” are structural and state violence: represented by Katrina’s flood waters and the implied police brutality of a police cruiser, which Beyoncé sinks by video’s end. Mostly, however, we see images of peace – of a young boy dancing before a line of police men in riot gear, who surrender to him rather than gun him down, just before a wall of graffiti reveals, “Stop shooting us.” Strange then that black life, not black death, elicits controversy. As Stacey Patton already noted, if we are not dying or placed in servitude to whiteness, then any affirmations of black love, black success, and black life will be an affront to white supremacy.

Fortunately, our black musicians since the first Negro spiritualist understood that music is willful resistance. Or as Nina Simone famously asserted: “An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times.” Beyoncé continues to build on a sturdy foundation that we, as African American intellectuals, must recognize and articulate in our quest for knowledge production and cultural affirmation.

Work Cited:

Stanfield, Peter. “An Excursion into the Lower Depths: Hollywood, Urban Primitivism, and St. Louis Blues, 1929-1937.” Cinema Journal 41, no. 2 (2002): 84-108.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Mainstream popular culture has become democratized over the course of the twentieth-century due to the efforts of afore mentioned artists listed above. As you point out, Janell, this democratization has expanded the use of popular culture to bring both marginalized groups (in this case black women and the black community as a whole) and community specific issues to the forefront. Although the popular culture provides an avenue for clearly expressing pressing concerns, we as historians and public intellectuals must examine and present to public audience the larger historical context of the issues facing America in the twenty-first-century. One of which has become blatantly obvious through the use of technology is the racial violence in America. And I say facing America and not only the African American community because both the sides of the argument are fixed in historical context. Muhammad’s The Condemnation of Blackness comes to mind when attempting to understand the normalization and systemization of racial violence. What are the arguments against the Blacklivesmatter movement, and why are they so persuasive for a large segment of the American population? What is the connection between systemic racial violence and urban sprawl?

Who, not simply what forces, act to create and recreate the systemic violence, and does that recreation produce meaningful changes?

While images in popular culture ably push contentious issues to the foreground for public appraisal, the historian as public intellectual must historicize the image and discussion. Janell certainly provides a launching pad for this latest instance of popular culture’s voice in the discussion.