The American Revolution, Race, and the Failed Beginning of a Nation

Although forms of systemic racism had certainly not gone away prior to Donald Trump’s election, that so many Americans voted for him as a way of publicly declaring their belief in various forms of American exceptionalism reveals the pervasiveness of racist ideas and institutions now and in the past. Understanding the distinction between slavery and race and the historical linkages between power, self-interest, and racial dominance go far in explaining the persistence of racial inequality and oppression. To this end, a review of ideas about slavery and freedom during the American Revolution also reminds us how race has changed while remaining rooted in American society.

Although we tend to think of democracy as a kind of absolute concept that refers to inherently ethical forms of social organization, it is an idea that does not reflect a hallowed and ahistorical commitment to human equality and justice. Democracy and its ideological cousin, freedom, have always been framed by the contest between empathy and the recognition of human equality and the desire to agglomerate and maintain power. While the writers of the United States Constitution understood concepts like freedom in broad philosophical ways, their usage of freedom was also bounded and qualified by specific economic, political, and religious interests. The Constitution expressed first principles for the founding of a new nation, yet it also contained all kinds of concessions made to ensure that arguments for racial equality would always be subordinated to the concerns of white people, however varied or paradoxical their concerns might have been. This is not an overstatement.

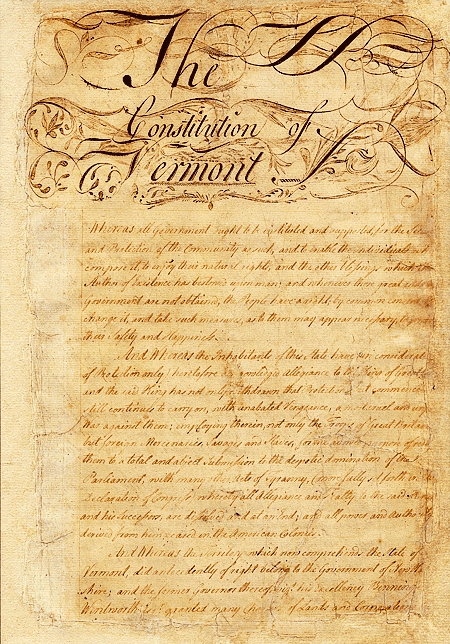

Yet, one might ask, how do you explain the persistence of racism when the northern colonies emancipated their slaves and ended the institution of slavery between 1777 and 1830? The answer is both short and complex. The short answer is that this process of ending slavery was uneven, compensatory and hesitant. By the early nineteenth century, in different ways, each of the former colonies, including New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New York, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and New Jersey had enacted abolition. Although not one of the original thirteen colonies, the new republic of Vermont would be included in this list with its 1777 constitution that declared,

“all men are born equally free and independent, and have certain natural, inherent and unalienable rights, amongst which are the enjoying and defending life and liberty; acquiring, possessing and protecting property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.”

This repeated the language of the Declaration of Independence, and it constructed freedom as an inherent condition of humanity.

Yet, this constitutional ending of slavery illustrated just one of several approaches to slavery’s northern end. In Massachusetts, a combination of slaves suing for their individual emancipation, an organized slave petition drive, black soldiers fighting against the British, a state constitution that declared the freedom of all men, judicial decree, white’s unease with their ideological hypocrisy, and a mixed economy that condoned but did not require slavery all pushed the decline of human bondage. In Pennsylvania, the greater reliance upon slave labor mandated compensation in the form of gradual emancipation laws. The Pennsylvania statute of 1780 ended slavery by shortening the period of “servitude” from perpetuity to 28 years. Even as northern states ended slavery, they continued to define black people as legal and political subordinates, as servants who had essentially been given a bit more room to make decisions for themselves.

A more complicated answer to the question of northern abolition lies in how ideas about freedom were changing by the time of the War of Independence. The notion that freedom and slavery were absolute opposite conditions of social and political experience gained broad acceptance by the time of the colonial revolt. Yet, the framing of freedom also drew rhetorical power from the reality that, in fact, white Americans always understood freedom in very specific historical terms. For example, recent scholarship has shown how the ideas of autonomy and of unfreedom clarify what late-eighteenth century people actually had in mind when they thought about freedom.1.

The Declaration of Independence had argued that “the political bands” binding the colonies to Great Britain could be severed because they were superceded by “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God.” Not only were these laws “self-evident,” they preordained that “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Deference to authority began to collapse in the wake of the idea that all people were deserved of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

However, the novel understanding of freedom as a form of unrestrained autonomy arose from the older idea that any individual was only as free as they were meant to be. Instead of freedom being understood as the ability to shape fully one’s destiny, older understandings of freedom had reversed this relationship. The status into which a person was born ultimately underlay and circumscribed their capacity to shape their environment and their future. Colonial political life was shaped less by a contrast between slavery and freedom, although black bondage was increasingly codified, and it was defined more by the idea of unfreedom. The life of any person was always defined by degrees of choice and degrees of circumscription.

Over the course of the eighteenth-century, people increasingly thought in terms of being either free or enslaved. Yet, most also thought that any person was free to a degree, even slaves. At the same time, most believed that no person was completely free from obligation, deference, or subordination within a hierarchical scheme, whether sacred or secular.

“…as Slavery is the greatest, and consequently most to be dreaded, of all temporal calamities: So its opposite, Liberty, is the greatest temporal good, with which you can be blest!”2

The same colonial discourse that highlighted the hypocrisy of the colonist’s rebellion in the name of “Liberty” also served to justify the idea that former slaves had been emancipated not because they had proven worthy of being freed, but because principle dictated that lifetime servitude should end. This logic lead many to emancipate their slaves while remaining unclear and fearful about what freedom would mean to and for black people. There could be emancipation in northern and southern colonies without abolition and without equality.

![Bobalition of Slavery ([Boston: s.n.] 1832?)](https://cdn.aaihs.org/2016/12/Bobalition.jpg)

Emancipation and abolition were different and the same. Emancipation only meant that one person had gained release from unending servitude. Abolition meant the necessary end of all lifetime bondage. Both sprang from the growing ideological chasm between slavery and freedom, but neither could close the widening gap between slavery and race. Both led to the end of slavery in the north, but neither diminished the idea, that in the realms of politics, religion, science, and daily routine, somehow black people remained lesser and should remain subordinate.

That racism would continue on without slavery marked a significant change in this pernicious phenomenon. However, the fact that racism has changed along with its historical contexts also explains why, yet again, it has reared up in such unequivocal and unyielding fashion. In consequence, it will continue to be a problem that so many people believe that it is necessary to “Make America Great Again” when America failed at its very beginning.

Chernoh Sesay Jr. is an Associate Professor of Religious Studies at DePaul University. He earned a Ph.D. in American History from Northwestern University in 2006. He is currently completing a book entitled Black Boston and the Making of African-American Freemasonry: Leadership, Religion, and Community In Early America. Follow him on Twitter @CMSesayJr1.

- François Furstenberg, “Beyond Freedom and Slavery: Autonomy, Virtue, and Resistance in Early American Political Discourse,” The Journal of American History, v. 89, 4 (March 2003), p. 1298; Jared Hardesty, Slavery and Dependence in Eighteenth-Century Boston (New York University Press, 2016) ↩

- (Ceasar Sarter (former slave), “Essay on Slavery,” The Essex Journal and Merrimack Packet, August 17, 1774 ↩

- Richard S. Newman, The Transformation of American Abolitionism: Fighting Slavery in the Early Republic (University of North Carolina Press, 2002). ↩