‘Stoolpigeons’ and the Treacherous Terrain of Freedom Fighting

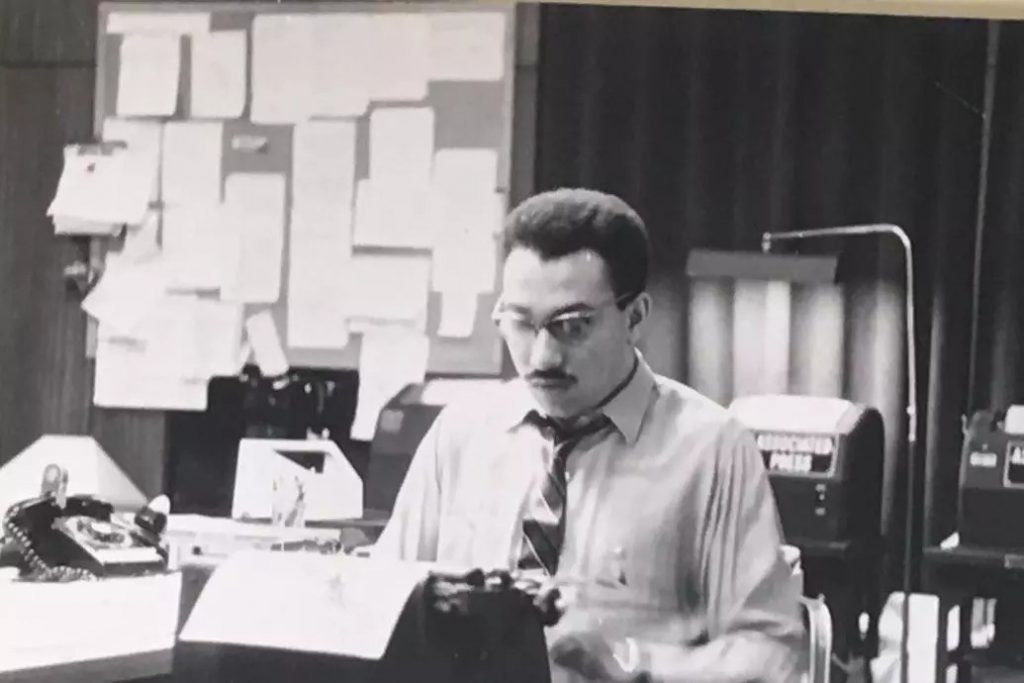

On May 15, 2018, Newsweek published a story entitled, “CIA Reveals Name of Former Spy in JFK Files—And He’s Still Alive.” In it, Richard T. Gibson was identified as a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) operative from 1965 to 1977. An exposé published a day after the Newsweek story, “What the Curious Case of Richard Gibson Tells Us About Lee Harvey Oswald,” reported that in 1962 Gibson resigned from the Fair Play for Cuba Committee (FPCC)—an organization he co-founded with Robert Taber in 1960—and offered his services to the CIA. An earlier article, “The Ghosts of November,” written by Anthony Summers and Robbyn Swan in 1994 and updated in 2001, included New Jersey FPCC member Hal Verb’s claim that members suspected Gibson of being a “stoolpigeon” very early on. When the authors presented him with evidence, including a letter released by the CIA that asked a commercial company to place Gibson on retainer on its behalf, he responded that it “sounded like” disinformation.

Indeed, Gibson has consistently denied allegations of cooperation with the government for several decades. In “Richard Wright’s ‘Island of Hallucination’ and the Gibson Affair,” for example, he wrote that he received a substantial award in a lawsuit against Penguin Books when Gordon Winter accused him of being a CIA agent, an agent provocateur, and a traitor. Likewise, a footnote in Chris Tinson’s Radical Intellect: Liberator Magazine and Black Activism in the 1960s explains that when the author asked Gibson about these allegations, he denied them and noted that he had won a libel case against persons who made such claims. Despite these denials, a multitude of documents are available that corroborate Gibson’s involvement with the CIA. This raises a number of interesting questions.

First, even as prominent figures including E. Franklin Frazier, Julian Mayfield, and Richard Wright raised suspicion about Gibson’s affiliations as early as 1959, activists such as Robert F. Williams, Max Stanford, and Vusumzi Make (former husband of Maya Angelou) purportedly defended him against these charges, at least through 1966.1 Why were Gibson’s nefarious affiliations blatantly obvious to some, but inconceivable to others?

Second, Gibson carried on a very long correspondence with Hodee Edwards, a Jewish woman married to an African American ex-patriate living in Ghana, throughout the 1960s. He had not met her in person at the time they became pen pals. Though Edwards had worked for one of Kwame Nkrumah’s closest allies, John Tettegah, she too had been accused of being an agent, not least by Shirley Graham Du Bois, who had warned Nkrumah that something was amiss with her shortly before the February 24, 1966 coup.2 Were Edwards and Gibson “birds of a feather,” both working to destabilize Black leftist liberation movements?

Third, Mayfield claimed that Gibson predicted events that transpired in Algeria that year—namely, the overthrow of Ahmed Ben Bella on June 19, 1965. This “sinister” revelation piqued Mayfield’s suspicion. Interestingly, the day of the coup Gibson was heading to Algeria from Morocco. He took handwritten notes over the next five days about the “Council of Revolution” that had ousted Ben Bella. These included denunciations of the former leader, notes about whether the Second Afro-Asian conference would still be held in Algiers, and information about various countries’ support of the new regime. Further, Gibson did not hide his disdain for Ben Bella before or after the coup. In 1965, he wrote, “Frankly, I never liked the man, considered him essentially weak, always ready to make every sort of promise under pressure, promises which he could not keep, lacking objectives and whose ‘leftism’ was mainly cheap demagogy.” He also expressed support for Ben Bella’s ouster and for Houari Boumédiène, and attempted to sell his article about the “true” nature of what had transpired in the “June 19 movement” to a number of progressive and leftist newspapers and magazines.3 Is it significant that Gibson, who had nothing but disdain for Ben Bella, was in close proximity to Algeria at the time of the coup?

The Richard T. Gibson Papers provide little in the way of direct confessions. In fact, quite the opposite is true. Throughout his correspondence from 1964 onward, Gibson deflects, denies, and ridicules the idea that he is a CIA operative though the allegations are numerous and persistent. Nonetheless, the archive provides a wealth of information about and insight into his tactics of concealment, evasion, and misdirection. In particular, he masterfully employs dominant discourses of Black Power, Third Worldism, and Tricontinentalism years before they became mainstream. The “Third World” as a political orientation was an internationalist formation that included all non-white oppressed persons who shared a common struggle, a common vision, and a common enemy: white Western imperialist society. It included those whose subjection was not ameliorated by the nominal gains of bourgeois civil rights and independence movements—the revolutionary masses, the superexploited proletariat, and militants engaged in urban rebellion and guerilla warfare.

Third Worldism was a historical development at the conjuncture of post-World War II global transformations, the Cold War, the ascendance of United States military and economic hegemony, and the insurgency of racialized, colonized, and oppressed peoples against Euro-American geopolitics. It was a theoretical position and discursive formation centered on anti-imperialism, anti-racism, anti-colonialism, and anti-capitalism. It was also a cultural and political enunciation of de-territorialized solidarity. In short, it offered a “third way” between the imposition of Euro-American capitalism and Soviet Union-style communism.

Gibson capitalized on the Sino-Soviet split, the popularity of Maoism, and the construction of African Americans as the vanguard of the revolution in the “belly of the beast” to discredit and cast doubt upon individuals, organizations, and nations that were integral to Third Worldism. He accused the Cubans of racism, revisionism, and genuflection to Moscow to explain why he was barred from the 1966 Tricontinental Conference. He condemned the non-violence of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee to encourage more “revolutionary” action in a possible attempt to steer the organization on a path that would invite government imposition. He also claimed that all those who questioned his affiliations were themselves tools of the CIA, imperialism, Trotskyism, or revisionism.4 These attempts at disparagement were meant to—and often did—invite dissent, disarray, surveillance, and violence. Moreover, Gibson accused those who disassociated from him because of his suspected CIA links of “McCarthyite behavior” and “witch hunts” to cajole them into “stat[ing] as fully as possible the nature and the details of the accusations made against [him] and… by whom they [were] made.” In other words, he promoted suspicion as a form of intelligence gathering. He also used that language, along with the fact that he had been “twice subpoenaed before the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee of the U.S. Congress” to legitimate his “leftist” credentials.5

African Americans like Richard Gibson, Julia Clarice Brown, and Lola Belle Holmes who supplied government agencies with a multitude of information about Black and Third World radical movements, organizations, and activism reveal the treacherous terrain freedom fighters were forced to navigate. These “stoolpigeons,” “turncoats,” and career informants made monumental challenges to racism, imperialism, colonialism, and capitalist exploitation all the more dangerous and difficult. The reality that “all skin ain’t kin” notwithstanding, one wonders how successful liberation struggle could have been without these persistent destabilization efforts.

- See e.g., Hodee Edwards to Richard Gibson, 24 October 1965; Richard Gibson to Hodee Edwards, 15 October 1966, Richard T. Gibson Papers (MS 2302), Special Collections Research Center, George Washington University (Gibson Papers hereafter). ↩

- Richard Gibson to Lionel (Morrison), 12 January 1966; Hodee Edwards to Richard Gibson, 27 May 1965; Hodee Edwards to Richard Gibson, 9 June 1966, Richard Gibson Papers. ↩

- Hodee Edwards to Richard Gibson, 24 October 1965; “19 June,” n.d.; Richard Gibson to Marc Abdalla Schleifer, 14 November 1965; Richard Gibson to Hodee Edwards, 2 November 1965; Richard Gibson to Hodee Edwards, 2 October 1965, Richard Gibson Papers. ↩

- See e.g., Richard Gibson to Sheila Patterson Horko, 14 January 1966; Richard Gibson to “Betita” (Elizabeth Martinez Sutherland), 28 July 1965; Richard Gibson to Mr. Leopoldo Leon, 20 June 1966, Richard Gibson Papers. ↩

- Richard Gibson to Mr. Leopoldo Leon, 20 June 1966, Richard Gibson Papers. ↩