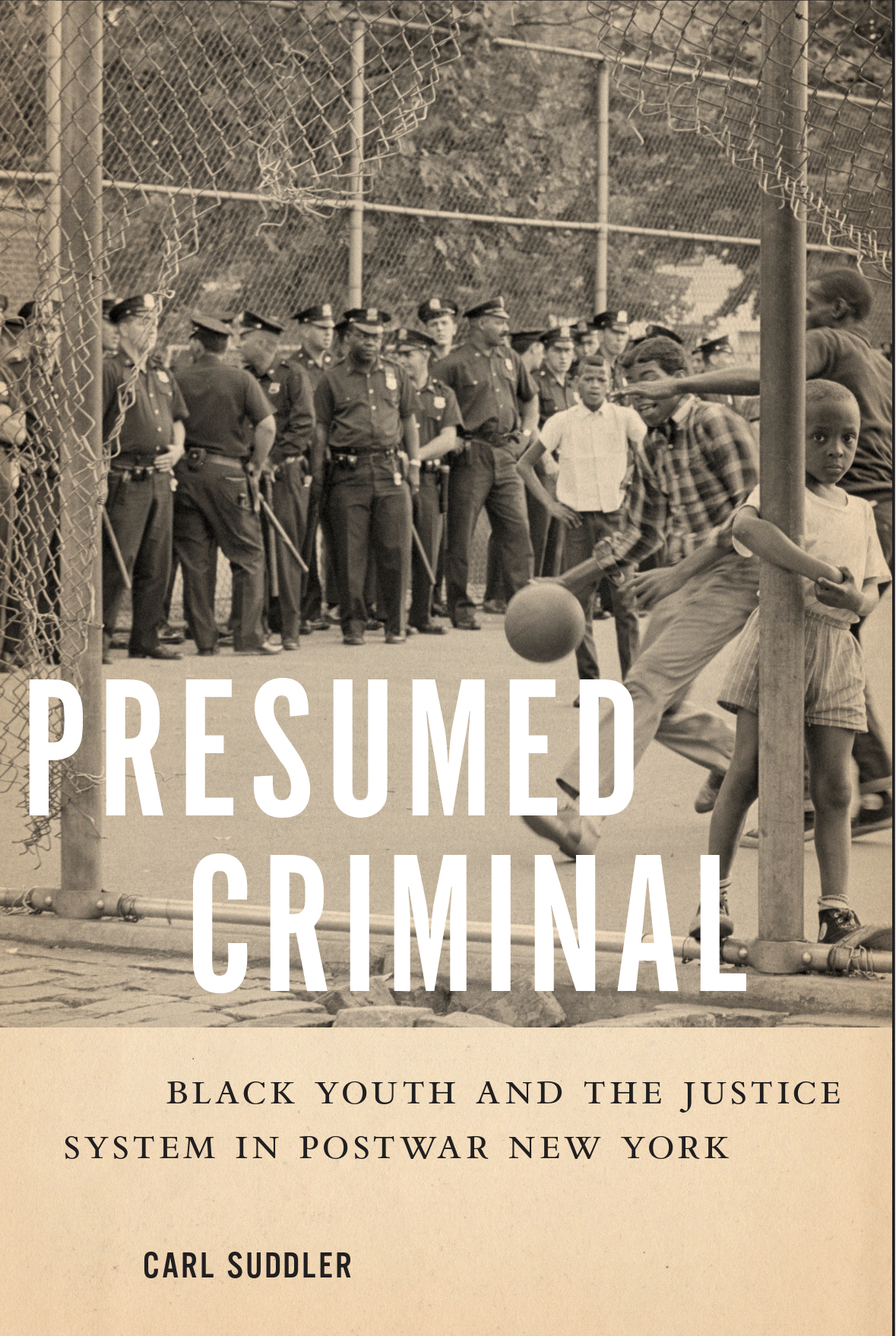

Presumed Criminal: A New Book on Black Youth and the Justice System in New York

This post is part of our blog series that announces the publication of selected new books in African American History and African Diaspora Studies. Presumed Criminal: Black Youth and the Justice System in Postwar New York was recently published by New York University Press.

***

The author of Presumed Criminal: Black Youth and the Justice System in Postwar New York is Carl Suddler, an assistant professor of history in the Department of History at Emory University. As a scholar of African American history whose research interests lie at the intersections of youth, race, and crime, Carl’s scholarship is committed to developing better understandings of the consequences of inequity in the United States. His research and teaching interests are related to twentieth-century U.S. history, African American urban history, histories of crime and punishment, the carceral state, sport history, and histories of childhood and youth. His other works has also appeared in scholarly and popular outlets such as the Journal of American History, Journal of African American History, American Studies Journal, as well as op-eds for The Conversation and Bleacher Report. Carl graduated from the University of Delaware with a B.A. in History and Black American Studies. He earned his Ph.D. in U.S. History from Indiana University. Follow him on Twitter @Prof_Suddler.

The author of Presumed Criminal: Black Youth and the Justice System in Postwar New York is Carl Suddler, an assistant professor of history in the Department of History at Emory University. As a scholar of African American history whose research interests lie at the intersections of youth, race, and crime, Carl’s scholarship is committed to developing better understandings of the consequences of inequity in the United States. His research and teaching interests are related to twentieth-century U.S. history, African American urban history, histories of crime and punishment, the carceral state, sport history, and histories of childhood and youth. His other works has also appeared in scholarly and popular outlets such as the Journal of American History, Journal of African American History, American Studies Journal, as well as op-eds for The Conversation and Bleacher Report. Carl graduated from the University of Delaware with a B.A. in History and Black American Studies. He earned his Ph.D. in U.S. History from Indiana University. Follow him on Twitter @Prof_Suddler.

“A timely and critically important origins story of how Black youth became over-policed and under-protected in one of the most liberal cities in America. They were victims of institutional racism and an increasingly hostile police force that refused to protect their right to protest and organize for racial justice. Young people’s bitter awakening to racial consciousness at the end of a police baton is, as Carl Suddler skillfully shows, the starting point for understanding why stop-and-frisk first made its debut in New York City over a half-century ago.”—Khalil Gibran Muhammad, author of The Condemnation of Blackness

J.T. Roane: What type of impact do you hope your work has on the existing literature on this subject? Where do you think the field is headed and why?

Carl Suddler: In Presumed Criminal, I point to a critical shift in the carceral turn between the 1930s and 1960s when state responses to juvenile delinquency increasingly criminalized Black youths and tethered their lives to a justice system that became less rehabilitative and more punitive. The work makes three important interventions. First, in Presumed Criminal, I challenge the notion that racial criminalization was predominantly a southern phenomenon. Here, my work joins other historians of the “Jim Crow North” who reveal how these “bastion[s] of liberalism” became pivotal battlegrounds in the postwar push for racial equality. This included, but was not limited to, contests over fair housing, public schools, and the criminal justice system––all spaces that directly impacted the lives of Black youths. Second, I sought to bridge a gap in juvenile justice history between the Great Depression and the Great Society. Many historians who examine the juvenile justice system, and often criminal justice more broadly, tend to focus either on earlier historical periods, like the Progressive era, or they jump into the postwar period, usually around the 1950s in this heightened moment of juvenile delinquency paranoia. This break leaves out a crucial transition in juvenile justice history. And, finally, in Presumed Criminal, I wanted to broaden the scope of the carceral state to include historical actors beyond the justice system in order to reexamine the nature and dynamics of crime prevention. This includes a number of societal forces, including politicians, print media figures, and social scientists, as well as celebrities and athletes, who joined carceral authorities in directing the public discourse on youth crime.

It is tough to know for sure where the field is heading and why. There are scholars out there invested in the people whose lives have been, and continue to be, drastically impacted by the expansive, and invasive, nature of the criminal justice system. I am one of them. Like many African American histories, Presumed Criminal was a labor of love written by you, for you. So, even though I was writing a history that is place and time specific, I was inspired to write it by the myriad of Black youths who have disappeared in the historical records and the ones who continue to bear the burdens of America’s past.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.