Prefiguring the African American “Postcolony”: Black Independent Schools and the Quest for Liberation

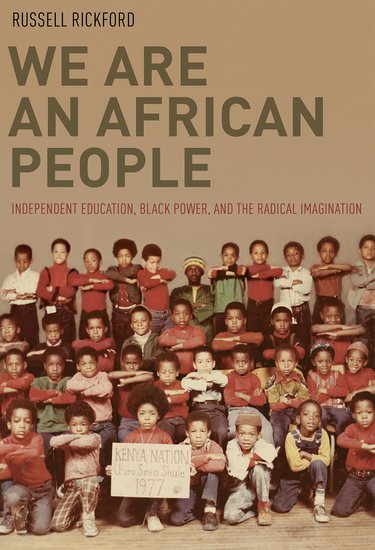

This week (April 25-30), we are hosting a roundtable on Russell Rickford’s We Are an African People: Independent Education, Black Power, and the Radical Imagination (Oxford University Press, 2016). Several scholars will offer reviews of the book and Russell Rickford will respond on the final day of the roundtable. We invite readers to join the discussion by leaving your thoughts in the comment section of the blog or by sharing your feedback on Twitter using the hashtag #WeAreAnAfricanPeople.

We begin with an introduction by our moderator Reena Goldthree, an Assistant Professor of African and African American Studies at Dartmouth College. She completed her undergraduate studies at Columbia University, earned a M.A. and Ph.D. from Duke University, and studied at the Institute for Gender and Development Studies at the University of the West Indies-St. Augustine as a Fulbright fellow. Her research explores the history of the African Diaspora in Latin America and the Caribbean with a focus on nationalism, migration, labor, and gender. Her current book project, Democracy Shall be no Empty Romance: War and the Politics of Empire in the Greater Caribbean, examines how the dislocations of World War I transformed political loyalties, racial identifications, and imperial policy in the British West Indies. Her publications include a chapter in the edited collection Global Circuits of Blackness: Interrogating the African Diaspora and forthcoming articles in the Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History and Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas. Goldthree currently serves on the editorial board of interdisciplinary journal, PALARA: The Publication of the Afro/Latin American Research Association.

We begin with an introduction by our moderator Reena Goldthree, an Assistant Professor of African and African American Studies at Dartmouth College. She completed her undergraduate studies at Columbia University, earned a M.A. and Ph.D. from Duke University, and studied at the Institute for Gender and Development Studies at the University of the West Indies-St. Augustine as a Fulbright fellow. Her research explores the history of the African Diaspora in Latin America and the Caribbean with a focus on nationalism, migration, labor, and gender. Her current book project, Democracy Shall be no Empty Romance: War and the Politics of Empire in the Greater Caribbean, examines how the dislocations of World War I transformed political loyalties, racial identifications, and imperial policy in the British West Indies. Her publications include a chapter in the edited collection Global Circuits of Blackness: Interrogating the African Diaspora and forthcoming articles in the Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History and Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas. Goldthree currently serves on the editorial board of interdisciplinary journal, PALARA: The Publication of the Afro/Latin American Research Association.

***

In We Are An African People: Independent Education, Black Power, and the Radical Imagination, historian Russell Rickford chronicles the black independent school movement during the late 1960s and 1970s. Deftly combining intellectual history with a rigorous attention to the local, national, and international currents that spurred the movement, Rickford illuminates the role of autonomous educational institutions in the quest for black liberation. By 1970, at least 60 Pan-African nationalist schools existed across the United States, principally concentrated in urban locales in California, New York, New Jersey, Ohio, Georgia, North Carolina, and the District of Columbia. Founded by veteran activist-intellectuals—many of whom were former members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)—these grassroots institutions included private preschools, K-12 facilities, and post-secondary campuses. Rooted in a “thoroughgoing critique of white cultural hegemony,” independent black schools combined academic instruction with robust political education, seeking to imbue students with a militant black consciousness and a deep commitment to black self-determination.1 As Rickford explains: “Pan African nationalist schools were far more than vessels of formal education. They were cooperatives, collectives, cultural centers, organs of community action and agitprop, and laboratories for a spectrum of ideas—from anti-imperialism and Third Worldism on the left to patriarchy and racial fundamentalism on the right.”2

Deeply researched and brilliantly argued, We Are An African People draws on archival materials, private papers, newspapers, pamphlets, and interviews to uncover the theory and praxis that shaped independent black schools. As Rickford acknowledges, black activists have often established “movement schools” as a component of mass struggle, including important earlier efforts by the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), Nation of Islam (NOI), and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Yet, the creation of Pan-African nationalist schools in the late 1960s and 1970s, Rickford writes, “signaled a strategic and philosophical shift from the pursuit of reform within a liberal democracy to the attempt to build the prospective infrastructure for an independent black nation, an entity that many activists imagined as a political and spiritual connection to the Third World.” 3 Indeed, while the activist-intellectuals who founded Pan-African nationalist schools drew inspiration from some domestic antecedents, they were most inspired by the writings of revolutionary figures from Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. As Rickford reveals, Che Guevara’s concept of the “New Man,” Julius Nyerere’s socialist vision of education as a tool for self-reliance, and the “bush schools” founded by guerilla fighters in Mozambique inspired and animated the political visions of independent school operators and teachers.

For the founders and administrators of Pan-African nationalist schools, the creation of independent educational ventures was not simply a means to secure educational autonomy. Rather, as Rickford insightfully argues, Pan-African nationalist schools functioned a form of prefiguration—an opportunity to enact “black cultural and political sovereignty” in anticipation of liberation. Drawing on theories of prefigurative politics, Rickford reveals that institution builders characterized African Americans as an internal colony and “viewed the classroom as the placenta of a nation.” Educational facilities thus served as a creative space for instantiating the new black nation—what Rickford deems the “African-American postcolony”—while living in the physical and legal borders of the United States. These institutions also served as local arenas to debate and deploy Black Power-era theories of internal colonialism.4

We Are an African People joins a rich body of scholarship that foregrounds the educational arena as a crucial site of black self-activity, consciousness raising, and collective struggle. The fight to control educational institutions, as Rickford reminds us, had implications far beyond the schoolhouse door. Recent studies of African Americans’ campaigns to remake educational institutions during the 1960s and 1970s—including work by Martha Biondi, Crystal Sanders, Komozi Woodard, Stefan Bradley, Ibram X. Kendi, and Richard D. Benson II—have linked battles for emancipatory education to campaigns to address the urgent material needs of black women, men, and children. Collectively, these new studies demonstrate the range of objectives black activists and intellectuals pursued in regards to education during the 1960s and 1970s, moving beyond the longstanding focus on desegregation.

This roundtable brings together leading scholars of African American history and Black Power Studies to assess the arguments and implications of We Are An African People. Rather than provide a critical overview of the entire work, each contributor will offer a focused analysis of a particular aspect of the book’s argument and consider how it contributes to our understanding of African American intellectual history, Black Power, and the Black radical tradition. In tomorrow’s post, Fanon Che Wilkins explores the dynamism of Black Power during the 1970s, calling attention to the changing ideological and political positions held by the cadres of activist-intellectuals who founded Pan-African nationalist schools. He situates We Are An African People in the burgeoning literature on Black Power while also raising new questions about the relationship between Pan-African nationalists and the black masses. On Wednesday, Ashley Farmer examines how patriarchal gender ideology shaped the movement to create and sustain independent black schools. She concurs with Rickford’s claim that patriarchy undermined black activists’ attempts to build schools for liberation, yet she also calls for a more detailed treatment of black women’s efforts to challenge gender constraints within the movement. On Thursday, Ibram X. Kendi interrogates the debates about African-American culture and folkways among the administrators of black independent schools. Kendi applauds Rickford for challenging the claims of Haki Madhubuti and other school operators who suggested that African Americans suffered from a degenerate culture and critiques the notion that the African American masses require rehabilitation as a prerequisite for liberation. On Friday, Derrick E. White highlights the contradictions between Pan-African nationalism as a political ideology and Pan-African nationalism as a guiding principle for building independent schools. As White points out, the pragmatic concerns of funding, staffing, and administering private educational institutions often stood in tension with the ideological aims of self-determination and self-sufficiency. Given the short existence of many of the independent schools examined in We Are An African People, Rickford’s work prompts important questions about the necessary preconditions for sustaining autonomous black institutions and the limits of prefigurative politics.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Excellent overview!!!!

Thanks so much! I’m looking forward to reading all of the reviews and to Russell Rickford’s response. It should be a great discussion.

I am looking forward to the dialogue. Much to discuss.

Thanks for joining us for the roundtable!! We look forward to hearing your feedback. We Are An African People raises so many pivotal questions about education as a site of mass struggle.

Hi Everyone,

I am looking forward to the discussion too. Hi Densu!

Sorry I missed this. Please keep me in mind for any future followup discussions.