Postal Work and the Struggle for Black Freedom

In late 1892, a railroad operator approached activist-journalist Ida B. Wells to inquire why the Black community of Memphis, Tennessee, had been boycotting the railroads. Wells replied, “Did you know Tom Moss, the letter carrier?” The railroad operator nodded that yes, he knew Tom Moss.

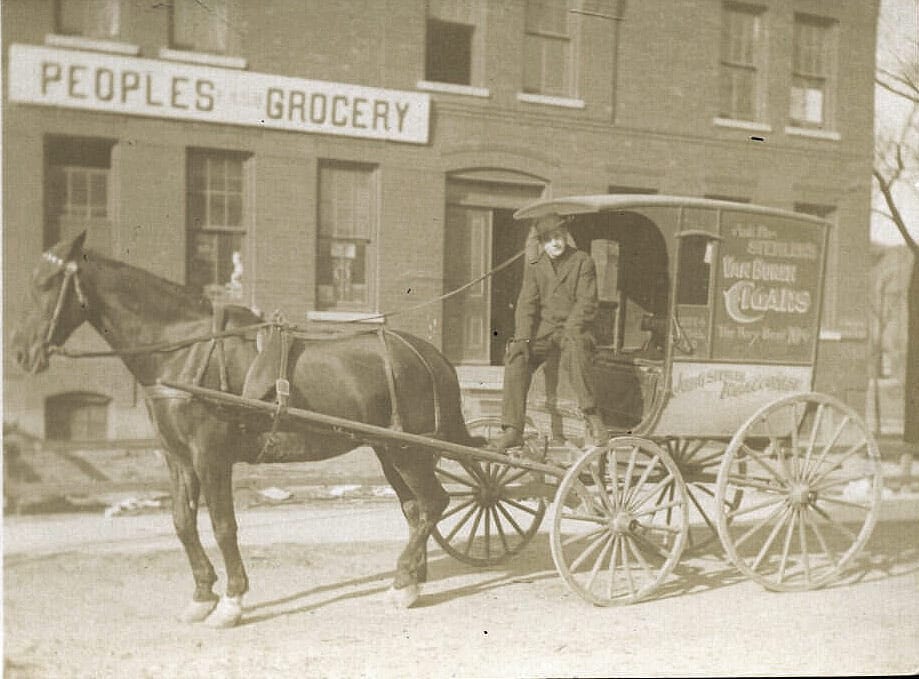

Thomas “Tommie” or “Tom” Moss was one of the first Black letter carriers in Memphis. He was a young and driven Black man in a city in which, Wells notes, a populous middle-class Black community had not faced a lynching since the Civil War. Moss partnered with his friends Calvin McDowell and Henry Stewart to open a grocery business called People’s Grocery Company just outside the city. Moss and his wife Betty had a young daughter, Maurine, and they were expecting a son. Ida B. Wells was a childhood friend of Tom Moss, and she was Maurine’s godmother. They saw each other regularly in part because Moss delivered mail to Wells’s office for her newspaper Free Speech. Indeed, Black postal labor and Wells’s muckraking brand of antiracist journalism joined forces to advance and advocate for Black communities. Ambitious and diligent, Moss worked seven days a week as a letter carrier to support his family and to fund his new grocery business. He would stop by People’s Grocery to check in with his business partners, and he often worked there at night.

One Saturday night, March 8, 1892, Black guards flanked the entrance to the store because the owners had reasons to suspect a white mob was forming not too far away from People’s Grocery. White supremacists from the area ranging from a competing white grocery store’s owner to the judge of Memphis criminal court raged at the Black business that they perceived to be stealing their Black customers. People’s Grocery had formally requested protection from Memphis police, but the police declined claiming that People’s Grocery was outside of their jurisdiction, as it was located in a predominantly Black middle-class suburb of the city. Wells speculated that Memphis policemen, too, joined in the angry white mob. Thus, when Moss arrived at People’s Grocery on Saturday night after his day job delivering letters for the U.S. Post Office, he would not have expected an ordinary night. Yet, he likely also expected to return to postal work the following morning, Sunday.

Tragically, Thomas Moss and his business partners Calvin McDowell and Henry Stewart did not live to see the morning light. White supremacist terrorists looted the People’s Grocery Company on Saturday night, March 8, 1892, which Wells noted were peak business hours: “Saturday night was the time when men of both races congregated in their respective groceries.” At 10pm, the Black guards shot a white looter. Because of that shot fired, police “dragged” Black men from around Memphis to jail. Wells describes that as Black men slept in jail, a “body of picked men” – angry white men carrying weapons intending to attack – identified the three partial owners of People’s Grocery and “dragged” them to a railroad track, where they lynched them. By all accounts including Well’s autobiography, Moss begged for his life for the sake of his wife and his unborn baby, before uttering his final words, “tell my people to go West – there is no justice for them here.” His business did not survive either.

Grief-stricken Wells refused to move on from this emotionally or professionally, bravely devoting her life to antilynching work. One cannot heal from that. Young Maurine Moss, still a toddler in 1892, “too young to express how she misses her father, toddles to the wardrobe, seizes the legs of the trousers of his letter-carrier uniform, hugs and kisses them with evident delight and stretches up her little hands to be taken up to the arms which will nevermore clasp his daughter’s form.” A sentiment preserved through Wells’s words, no image better encapsulates the promise, the peril, and the heartbreak of late-nineteenth century Black postal work. Thomas Moss was well-known, well-respected, and well-off enough to become an entrepreneur because of his letter-carrying work for the federal government.

Alas, in Moss’s case as well as others, the power of a federal postal worker could not overcome the racist terror of white supremacists in postbellum society, even on the northern end of the South. Wells argues: “The power of the State, county and city, the civil authorities and the strong arm of the military power were all on the side of the mob and of lawlessness.” When African Americans discovered limited autonomy and power, white supremacist violence signaled otherwise. Becoming a prominent Black business owner like Thomas Moss with predominantly Black patrons could be deadly. In the aftermath of the People’s Grocery Lynching, however, Black Memphians with Wells at the helm began to express their exasperation by boycotting northern-operated railway lines. Thus, when an indignant railroad operator began to question Wells, she replied simply, “Did you know Tom Moss, the letter carrier?” He nodded that yes, he knew Tom Moss.

Despite limited success, this boycott led to angry white mobs demolishing the offices of Wells’s newspaper business, Free Speech. She migrated further north to escape death threats in Memphis. In 1896, she co-founded the National Association of Colored Women’s (NACW) Clubs, and in 1909 she co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

The tragic 1892 lynching of letter carrier Thomas Moss fueled the antilynching work of his close friend Ida B. Wells throughout her career. The lasting influence of her beloved friend displays the fierce pursuit of righteousness by Wells and re-enforces the centrality of interest groups across the national political landscape in the years following Reconstruction and throughout the Progressive Era. Further, this story reaffirms the importance of the Post Office in African American history through the lens of Thomas Moss. Indeed, Wells never forgot her childhood friend, Tom Moss, the letter carrier.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.