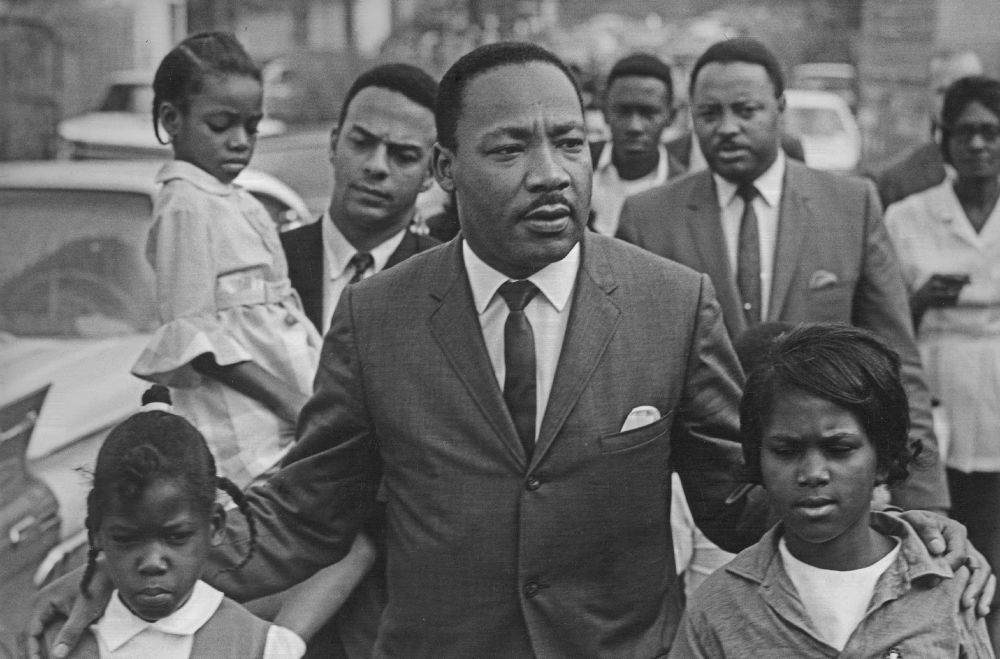

Martin Luther King Jr. on Making America Great Again

On February 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. stood before the congregation of Ebenezer Baptist Church, and preached his final sermon there—“The Drum Major Instinct.” Ominously, King admitted that he occasionally thought about “life’s final common denominator—that something we call death.” King, sensing that his days were numbered, went on to soberly dictate how he wished to be memorialized at the time of his death. He specifically forbade those who survived him from mentioning his Nobel Peace Prize or other superficial markers of success. Instead, he instructed those in attendance to only highlight the one thing he viewed as his singular accomplishment: “I’d like somebody to mention that day that Martin Luther King, Jr., tried to give his life serving others…I want you to say that I tried to love and serve humanity.”

As a Christian minister, King summarized his life in this manner, because he firmly believed that, “Jesus gave us a new norm of greatness. If you want to be important—wonderful. If you want to be recognized—wonderful. If you want to be great—wonderful. But recognize that he who is greatest among you shall be your servant.” According to King, Jesus taught that the drive to be great is an admirable instinct when greatness is evaluated by how much one serves others. Armed with Jesus’s precept, King called upon his parishioners to redefine greatness by becoming drum majors in the quest for justice, peace and righteousness.Today, as the nation celebrates the life of King, it would behoove us to take a moment to fully interrogate our definition of greatness.

How the nation chooses to define greatness will have grave implications. On the one hand, we can choose to “make America great again” by embracing an ethos of xenophobia, misogyny, and racism, as has been advocated by the current President of the United States. According to this definition of greatness, we should always put America first, even when others are desperately in need of assistance. Thus, when asylum seekers arrive at our borders, the President’s definition of greatness dictates that we give in to a politics of fear and turn them away on the flimsy premise of their proclivity to violence. In contrast, King called upon Americans to redefine greatness by embracing an ethos that he called “dangerous altruism.”

For King, dangerous altruism was epitomized by the protagonist of the Good Samaritan parable. In this biblical story, Jesus tells of a man who is left for dead by a gang of robbers on the side of the very dangerous Jericho Road. Despite being on the precipice of death, a priest and a Levite passed him by pretending not to notice his grave condition. However, the third passerby—a Samaritan—not only showed concern by stopping, but he also administered aid and ensured that the man’s condition was significantly improved. King speculated that perhaps the others did not stop out of sheer fear. According to King, the fear caused those who passed him by to ask, “If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?” The difference between them and the Good Samaritan was that the Samaritan reversed the question, and asked, “If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?” According to King, the Samaritan “was a great man because he had the mental equipment for a dangerous altruism. He was a great man because he could rise above his self-concern to the broader concern of his brother.” Similarly, as Americans, we have an opportunity to redefine greatness by setting aside our fears, and asking ourselves what will happen to the asylum seekers at our border if we do not stop to help them. In order to make America great again, we must embody a dangerous altruism.

However, altruism is not enough; especially if it consists of merely engaging in a form of philanthropy that simultaneously preserves unjust structures. In King’s final book-length manuscript, Where Do We Go from Here, he once again draws upon the Good Samaritan parable, but this time he uses it to call upon Americans to undergo a “revolution of values.” King offered. “A true revolution of values will soon cause us to question the fairness and justice of many of our past and present policies. We are called to play the Good Samaritan on life’s road side, but that will only be an initial act. One day the whole Jericho Road must be transformed so that men and women will not be beaten and robbed as they make their journey through life. True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar, it understands that an edifice which produces beggars, needs restructuring.”

In King’s interpretation of the parable, the Jericho Road has become an analogy for contemporary manifestations of structural injustice. As Iris Marion Young explains, “Structural injustice, then, exists when social processes put large groups of persons under systematic threat of domination or deprivation of the means to develop and exercise their capacities,” she continues, “at the same time these processes enable others to dominate or to have a wide range of opportunities for developing and exercising capacities available to them.” Thus, the Jericho Road is meant to represent those social processes that all members of society participate in, which enable some members of society to flourish while simultaneously making others—mostly non-white and poor—more vulnerable to domination and deprivation. With this in mind, the endangered man symbolizes those who suffer as a result of structural inequality. As King explained, the wounded man represents “any needy man—on one of the numerous Jericho roads of life.” Unlike those who believe that it is enough to fling a coin at the impoverished through various philanthropic measures, while leaving structures of injustice wholly intact, King argued that the entire edifice must be restructured. Thus, if we want to make America great again, we must do so by transforming those structures that allow some to flourish, while foreclosing opportunities to others.

Finally, it’s important to note that King’s beliefs about responsibility for transforming structures of injustice spilled beyond America’s borders. For instance, he argued that global capitalism and international commerce have structured the world in such a way that the typical American participates in social processes, which impact people all across the world, before they even leave the house each morning:

You get up in the morning and go to the bathroom, and you reach over for a bar of soap, and that’s handed to you by a Frenchman. You reach over for a sponge, and that’s given to you by a Turk. You reach over for a towel, and that comes to your hand from the hands of a Pacific Islander. And then you go on to the kitchen to get your breakfast. You reach on over to get a little coffee, and that’s poured in your cup by a South American. Or maybe you decide that you want a little tea this morning, only to discover that that’s poured in your cup by a Chinese. Or maybe you want a little cocoa, that’s poured in your cup by a West African. Then you want a little bread and you reach over to get it, and that’s given to you by the hands of an English-speaking farmer, not to mention the baker. Before you get through eating breakfast in the morning, you’re dependent on more than half the world.

King introduced this anecdote as a means to make the claim that: “All life is involved in a single process so that whatever effects one directly affects all indirectly.” In another sermon, King reinforced this point, by recounting his recent trip to India. Reflecting on the poverty he witnessed, King introspectively queried whether Americans had a responsibility to alleviate the woes of the Indian people. He concluded that they did “because the destiny of the United States is tied up with the destiny of India.” According to King, America had an imperative to “use our vast resources of wealth to aid these undeveloped countries that are undeveloped because the people have been dominated politically, exploited economically, segregated, and humiliated across the centuries by foreign powers” (emphasis added). In other words, King is making the claim that India’s destiny was, and is, inextricably bound to America’s imperialist pursuit of its own destiny.

Applying King’s lesson to our contemporary moment, it is immoral for us to put America first, if that means turning a blind eye to the suffering of other nations. Instead, we are called to redefine greatness by transforming those global edifices that produce the suffering incurred by atrocities such as poverty and war. With these lessons in mind, let’s both honor King and make America great again by redefining greatness.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Excellent article! It’s too bad that those who need to see it most will not.