Martin Luther King Jr. and Milwaukee: 200 Nights and a Tragedy

*This post is part of our forum on Martin Luther King Jr.’s impact on American cities.

The tragic murder of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968 sent shock waves rippling outward from Memphis leaving no community untouched. The news of the assassination affected America and its citizens in profound ways. Tears of sorrow fell amidst deep mourning while flames began to spread throughout dozens of urban centers. Marchers in the streets honored the young leader’s memory and held on to hope at any cost. Others sought to be heard at any cost. No matter the response, the loss was dramatic.

In Milwaukee, a photojournalist brilliantly captured a young man’s raw pain visible in a lone tear streaking down his cheek. The quiet, poignant image illuminated the city’s broader suffering and stood in stark contrast to bold headlines of loss and destruction in other American cities. Milwaukee’s newspapers were filled with aerial views of smoke plumes rising from urban centers. Pictures documenting the militarization and presence of National Guardsmen along glass-strewn sidewalks in other cities dominated the view. Milwaukee had somehow been spared this time.

Sorting through this type of rubble rarely provides easy answers, even with five decades worth of hindsight. Similarly, assessing impact feels indefinite, but within weeks of the assassination, Milwaukee’s energetic campaign demanding fair-housing legislation became inextricably linked with slain civil-rights leader’s legacy.

King’s swift ascent into the most recognizable leader in the struggle for equality and racial justice left a lasting impact on our nation’s history. King’s urgent critiques of structural racism, capitalism, and militarism — and conviction that the nation reckon with racial injustice everywhere — transformed the arc of America’s Black freedom struggle. Still, this critical legacy has proved malleable over the decades.

Depending upon the need, King’s legacy has been shaped and reshaped by the media and sanitized by politicians and others for public consumption. Historian Jeanne Theoharis’s most recent book dissects and challenges scores of civil rights myths, including several about King himself, which many have come to accept. For decades, a wide range of historians and scholars have worked to assess King’s impact while also re-positioning his legacy in relation to other leaders and ordinary citizens involved in the struggle. King inspired and led, but he was also a servant to the movement’s foot soldiers. By shining a light elsewhere, scholars have unearthed lesser known, but equally inspiring, stories of leadership, sacrifice, and conviction. Highlighting the impact of individual actors in history — and acknowledging agency — is always a timely and powerful reminder, especially during today’s political climate.

My most recent scholarship is situated in the North and West far from the Deep South where King’s legacy was firmly anchored. In Milwaukee, I have come to know a struggle no less complex than King himself. Milwaukee’s civil rights past defies easy categorization and makes clear no single campaign was part of a monolithic movement playing out nationwide. Perhaps more importantly, grassroots struggles depended upon local leaders who may have admired King and adopted useful tactics. But others adapted or rejected King’s approach in search of alternatives that made sense on the ground in their own community far from where luminaries were based.

Martin Luther King Jr. and Milwaukee

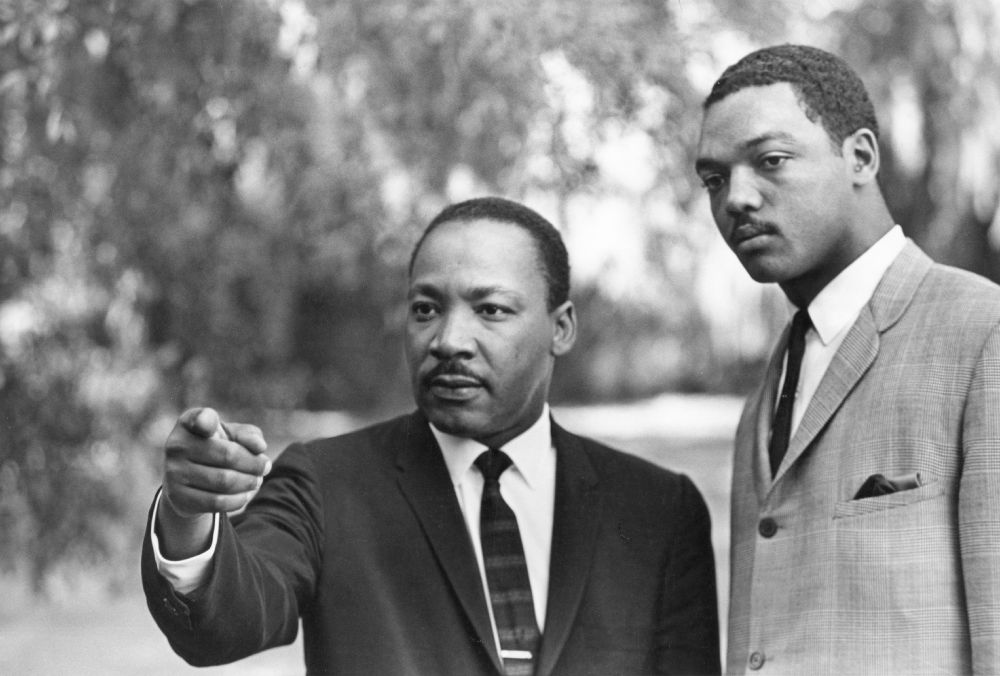

King traveled extensively and reminded crowds often that “the racial issue we confront in America is not a sectional but a national problem.” His thoughtful observations during press interviews and soaring proclamations to overflowing crowds about injustices rang true to Black Americans everywhere, including those in Milwaukee. King first visited the city in 1957, shortly after the successful conclusion of the dynamic Montgomery Bus Boycott. Speaking before a crowd of 1,200 at the invitation of the Milwaukee branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), King challenged the crowd “to refuse to cooperate with segregation and discrimination even when the price might be jail or death.”1

King’s anointment as the most visible leader and spokesperson for the rousing civil rights movement was nearly complete by the time he returned to Milwaukee in January 1964. Local alderwoman, Vel Phillips introduced King to the crowd of 6,000 and outlined the local struggle for equality. King reflected upon his experience in Birmingham waging vigorous battles against entrenched segregationist forces. The brutal repression and thuggish violence demonstrators faced — captured on film and in news photographs published worldwide — garnered significant awareness and sympathy for the movement.

King returned a third and final time in November 1965. Speaking at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, he called for an end to discrimination, especially the school segregation plaguing local schools. King demanded action on employment discrimination and a minimum wage increase while nodding to the seething and dangerous conditions in inner cities. King’s stature had risen even higher since the dramatic Selma to Montgomery marches and monumental legislative victories — the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965. His legacy was all but solidified with the Southern struggle, but the landmark legislation had little impact on those suffering up North and beyond Dixie.

Cities beyond the South rarely figure into the dominant civil-rights narrative most schoolchildren learn today, but grassroots campaigns were conceived of, built by, and waged locally by local activists and ordinary citizens all across the nation. In Milwaukee, parents, religious leaders, and activists picketed burger chains and targeted employers known to discriminate. They organized school boycotts, set-up Freedom Schools, and led a massive school desegregation effort. Youth grew up active in the struggle. Milwaukee leaders and activists attended the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, heeded Dr. King’s ecumenical call to head to Selma, and volunteered during Freedom Summer and elsewhere in the South. Yet, many returned home to confront the injustices they knew existed in their own Northern city.2

Problems facing Black Milwaukee included employment discrimination, police brutality, and segregation in education, but it was housing discrimination that proved especially pernicious. With each passing decade, tens of thousands of new Black residents found themselves pinned in the city’s largely segregated Inner Core. Blacks endured housing shortages, poor conditions, and high rents. Local activists took up the issue in 1967 in what turned out to be the city’s most tumultuous civil rights battle.

Let the Youth Lead

Established in 1948, Milwaukee’s NAACP Youth Council became more confrontational during the mid-1960s. The group’s adviser, Father James Groppi, sought to educate the young activists and help them chart their own unique approaches to issues. The creation of a self-defense corps in 1966 added a degree of militancy to the group and reflected a need to protect themselves and their supporters during confrontational direct-action efforts.

The Youth Council members were also astute visual strategists, increasingly aware of their ability to attract press coverage and photography’s ability to advance the local struggle for racial justice. The Milwaukee NAACP knew that organizers like Dr. King carefully orchestrated demonstrations and direct-action efforts to generate press coverage to help sway national opinion and compel the federal government to act. In a similar fashion, the young activists sought to turn Milwaukee upside down over open housing with a series of marches into the city’s white South Side neighborhoods just weeks after Milwaukee’s 1967 summertime civil disturbance.

On August 28, 1967, a small band of interracial marchers encountered swelling crowds of angry white counter-protesters and little police presence. The fair housing demonstration — and violent reactions — generated extensive news coverage.3 Massive crowds ranging from 5,000 to 8,000 people returned on the second night and pelted marchers with stones, bricks, bags of urine, firecrackers, and bottles as they passed by.4. This riotous spectacle of massive resistance to the daily open-housing protests rattled the city and dominated local news for weeks.

Unwilling to back down, the Milwaukee NAACP Youth Council vowed to march until the city outlawed housing discrimination. News of the “Racial Strife That’s Making Milwaukee Infamous” — as a Jet magazine headline called it — quickly spread and an ecumenical call brought religious leaders and regional activists to town for massive marches. While some hoped King might lend a hand, a September 4, 1967 telegram assured he supported their effort and believed it was the “kind of massive nonviolence that we need in this turbulent period. You are demonstrating that it is possible to be militant and powerful without destroying life or property.”

Like others, King recognized the “Miracle in Milwaukee” as a dynamic movement — spearheaded by militant black youths led by a white priest adviser — which largely contradicted the prevailing assumption that an integrationist, church-based campaign was no longer possible. As historian Patrick Jones has argued, the activists remained nimble and fashioned their own versions of nonviolent direct action and self-defense as they melded traditional notions of civil rights and Black Power into a set of tactics that fit Milwaukee’s changing dynamics. They professed nonviolence but were unafraid to defend themselves. The Youth Council challenged city officials and forced police into action — they blocked traffic and changed routes, and set strategies by group vote, refusing to be led by a single, charismatic leader.

Their stamina would prove surprising as well. The energetic youth marched for 200 nights in a row logging hundreds of miles throughout the city. Their disruptive approach and tactics called attention to the drastic need for change gaining national, even international attention, along the way. Senator Walter Mondale referenced the ongoing Milwaukee marches in February 1968 in support of an open-housing amendment, but on March 30, 1968, the Milwaukee youth called off the marches. Less than a week later, King was brutally murdered.

Assassination

With the city on edge and leaders calling for calm after King’s assassination, Father Groppi, the Milwaukee NAACP Youth Council, and other activists staged the city’s largest demonstration ever with more than 15,000 people marching in King’s honor. Just days after Milwaukee’s overwhelmingly peaceful march, the United States Congress passed, and President Johnson signed, federal housing provisions into law as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1968. The tragic intertwining of King’s terrible death and Milwaukee’s crucial role in advocating for housing legislation remains a bitter irony of a tumultuous era.

Dr. Martin Luther King’s true significance was stunted on April 4, 1968, but his life continues to inspire those in Milwaukee and beyond. It is vitally important to continue to unravel the myths, rewrite uninspiring narratives, and reclaim King’s true radical vision. There is much to learn from the successes and missteps of leaders and ordinary citizens alike. Today’s young leaders will recognize more than tragedy alone. There is no shortage of inspiring individuals — ordinary people in cities and small towns from coast to coast — who modeled steadfast commitment, conviction, and hope, before and since King’s powerful life ended.

- Quotes from “Long, Long Way to Go, Negroes Told,” Milwaukee Journal, August 15, 1957, part 2, pg 14.; “’Love Oppressors’ Rev King Urges,” Milwaukee Journal, Jan 28, 1964, part 2, pg 1, 8. ↩

- Margaret (Peggy) Rozga, interview by Mark Speltz, March 30, 2007; Margaret Rozga, “When Civil Rights Were on the Rise,” The Humanist, November 1, 2006. ↩

- “Youth Council, Groppi Carry Open Housing Protest to South Side,” Milwaukee Journal, August 29, 1967. ↩

- Margaret Rozga, “March on Milwaukee,” Wisconsin Magazine of History, 90, no. 4 (Summer 2007): 28–39. ↩

I enjoyed Mark’s article. I would add that while Dr. King did not come to Milwaukee and participate in the historic open housing campaign there in 1967-68, he saw something critically important in what Fr. Groppi and the NAACP Youth Council/Commandos were achieving there with their brand of militant nonviolence. Recall that the year before events in Milwaukee, down the highway in Chicago, King had not been very successful with the Chicago Freedom Movement and had left with many questions circling around him about the viability of non-violent direct action in the urban North. Black Power was on the rise and King was doing some significant soul-searching. As the Milwaukee open housing campaign exploded in August of 1967, attracting national press and hundreds of pilgrims to the city to support the demonstrations, an inspired King sent a telegram to Groppi and Youth Council/Commando leaders stating, “Your actions inspire me deeply. I have recently contended that we in the civil rights struggle must find a middle ground between riots and sentimental and timely supplications for justice. This means escalating nonviolence even to the scale of civil disobedience if necessary. What you and your courageous associates are doing in Milwaukee will certainly serve as a kind of massive nonviolence that we need in this turbulent period. You are demonstrating that it is possible to be militant and powerful without destroying life or property. Please know that you have my support and my prayers. You are moving the great tradition by those who are willing to stand up for righteousness sake and you are motivated by a deep commitment to christianity. May god bless you and yours in all of your creative and courageous endeavors.”

Patrick Jones

The Selma of the North: Civil Rights Insurgency in Milwaukee