Getting the Word Out: The Circulation of Black Power Newspapers

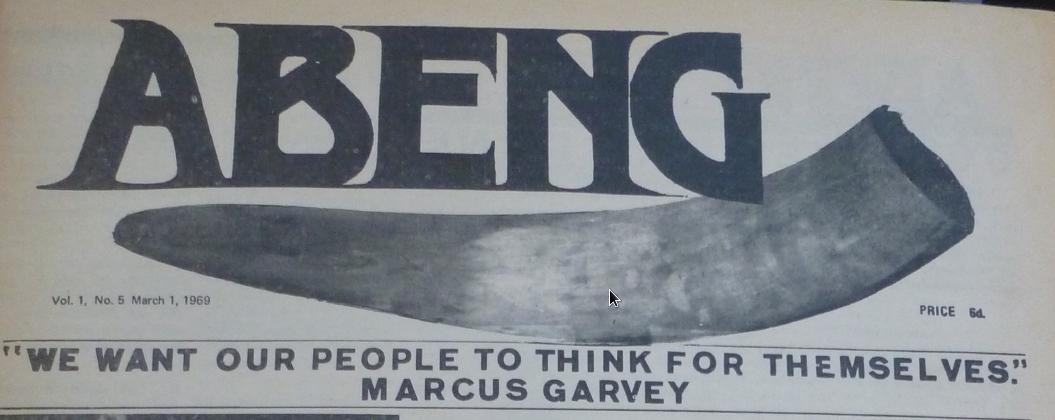

Back in October, I wrote about Abeng, the short-lived Jamaican radical newspaper which, in the late 1960s, played a central role in articulating distinctly Jamaican and West Indian approaches to Black Power. That first post focused mostly on the issues that defined much of West Indians’ approach to Black Power and on the ways in which Abeng reflected the West Indian Black Power movement’s rootedness in a long regional history of oppositional thought. In this post, I want to focus on the circulation of the newspapers that were so important in disseminating the ideas that drove Black Power activism.

Much of the source material that I used for my dissertation came from small-circulation newspaper like Abeng. I used the radical press, community newspapers and magazines and especially campus newspapers to trace how young Black activist intellectuals in the Commonwealth Caribbean and Canada (where many young West Indians migrants came, often to attend university) formulated distinct approaches to Black Power. Print culture, is, of course, a crucial resource for tracing the development of radical thought. That said, a focus on the content of newspapers like Abeng does not tell us very much about the people who read those papers, or how those papers got into readers’ hands. Moreover, as several people pointed out when I workshopped various parts of my dissertation, such a focus risks “overselling” the importance of a particular text if the researcher cannot say with any certainty if a critical mass of people actually read it. Writing about texts was one thing, but thinking about and researching the histories of how those texts circulated was a particular challenge for me. This month, in order to get a somewhat richer picture of how print culture opened up a space for dialogue between writers and readers in the Black Power era in Canada and the Caribbean, I’d like to talk a little bit about how two papers, Abeng and Uhuru, a Montreal-based newspaper that ran roughly simultaneously with Abeng, made their way to readers.

On 30 March 1969, only about eight weeks after Abeng’s debut, Denis Sloly, an attorney and a member of the paper’s board died in an automobile accident. The next issue of Abeng was dedicated to Sloly’s memory and included tributes from noted activist intellectuals including George Beckford, Rupert Lewis, and C.Y. Thomas and Ras Negus, a leader in Kingston’s Rastafari community.

Even though Sloly was a lawyer, his duties with Abeng included the difficult work of distributing and selling the paper. Beyond the heartfelt appreciation for his activism that was expressed by Sloly’s colleagues, perhaps as a way to acknowledge that a professional was ready to haul bundles of newspapers across the island and thereby encourage other salespeople to redouble their own efforts, Abeng’s tribute reproduced the last distribution report that Sloly filed. This document gives us a valuable insight into how the producers of a paper like Abeng, working with a shoestring budget and without the support of established distribution networks, got the paper out to readers every week.

Nine days before he died, Sloly went to Montego Bay to distribute the most recent edition of Abeng (only the eighth one) and to make contact with people who would be interested in selling the paper. Sloly’s report suggests that, at least in Montego Bay, Abeng’s distribution relied extensively on a loose network of activist-minded youth and young men looking to pick up some extra cash. This informal structure created problems for Sloly. One contact returned hundreds of unsold copies of the paper because it was unclear to him how he or his sub-distributors were supposed to get paid, so he didn’t sell them. Moreover, Sloly’s obvious unfamiliarity with Montego Bay and with the people working to sell the paper—he describes getting lost a few times and has, at best, sketchy information on the identities and whereabouts of a number of his distributors or potential distributors—hint at the challenges involved in ensuring regular distribution outside of Kingston. 1

Coming far from Kingston, but equally a part of the broad history of West Indian radical thought and activism, Uhuru was a newspaper produced largely by members of Montreal’s rapidly expanding West Indian community in 1969-1970. The paper was in many ways a legacy of the Sir George Williams Affair, a 1969 protest at the Montreal University of that name (now Concordia University), in which West Indian and other Black students occupied the university’s computer lab in protest of the university’s handling of charges of racism that had been brought against a biology professor. Many of Uhuru’s contributors and editorial staff had been directly involved in the protest, and nearly every issue of the paper addressed the legal and political fallout of the protest in some way. Like many Black radical papers, Uhuru had one eye on local issues of particular relevance to Black readers and one eye on the struggles of Black people worldwide. Uhuhru positioned itself as the voice of Montreal’s Black communities, reporting on local episodes of racism, running stories about the history of Black people in Canada and informing Black Montrealers about the resources available to them, while also reporting on Black activism in the United States, the West Indies and Africa.

Uhuru was particularly dedicated to fostering relationships with Black youth in Montreal. (1 June, 1970.)

Montreal is a key site in the history of Canadian Black activism and the city’s vibrant and intellectually fertile Caribbean community meant that the city also played an important role in the development of 1960s West Indian radical activism. That said, the relatively small size of the city’s Black population meant that Uhuru struggled to make ends meet. The paper averaged sales of 2500 copies of each issue, well below a financial break-even point of 3000. Locally, most of Uhuru’s sales came through the work of vendors working the city’s streets. While this probably meant that the paper encountered some of the same challenges involved with relying on informal labour that Sloly described in his report, Uhuru’s management also thought that relying on street sales created a gap between themselves and potential readers. They saw an encounter between a vendor and someone walking along the street not simply as a potential sale, but as a step towards building community and starting a dialogue about the issues that they were concerned about, something that the people selling the paper were not always equipped to do. Clarence Gittens, Uhuru’s circulation manager, noted that customers expected vendors to be “able to articulate fully the views, aims and objectives” of the paper, which was, presumably, not always the case. Another problem with street sales was their inherently inconsistent nature in a city known for its brutal winters, when sales dropped by over 50% as compared to summer months. 2

While Uhuru was unable to develop the solid local readership that would have helped it stay afloat, it had remarkable success in creating a community of readers from geographically diverse locations. The paper was available at several locations in Toronto and New York City, and most of its 400 mail subscribers were from outside of Montreal. Uhuru’s letters-to-the-editor reveal the widespread nature of the paper’s readership; correspondence came from across the Anglophone Caribbean, as well as from readers in the United States and Great Britain. Of particular interest are two letters from Africa. One was from Walter Rodney, who had moved to Tanzania after his ouster from Jamaica following his return from the October 1968 Congress of Black Writers, held in Montreal; Rodney offered to share literature he was collecting from freedom fighters in Dar Es Salaam with Uhuru, as “news from the battle front will always be of interest.” 3 The second was from Stokely Carmichael (who gave the keynote at the Congress of Black Writers) and Miriam Makeba, who wrote from Conakry to compliment Uhuru and to let the editors know that Kwame Nkrumah thought Uhuru was “by far one of the best [newspapers] in print today.” 4

The fact that letters came to Uhuru from so many diverse locales is a testament to the important role that activists in Montreal played in the development of Black Power as a transnational political and intellectual movement; it also keeps me curious about the networks, connections and circumstances that helped print culture, and the ideas it carried, circulate.

- Denis Sloly, “His Last Route Report,” Abeng, April 5, 1969. ↩

- Clarence Gittens, “Circulation Commentary,” Uhuru, July 13, 1970; Yvonne Strachan, “Subscription Commentary,” Uhuru, July 13, 1970. ↩

- Walter Rodney, Uhuru, 24 November 1969. Dar Es Salaam was home to a number of political groups fighting white supremacy and colonialism in southern Africa. ↩

- Stokely Carmichael and Miriam Makeba, Uhuru, 2 February 1970 ↩

I enjoyed your article. I am also working with Black Power periodicals (some fairly obscure) and trying to unearth the intellectual networks they reveal. My particular interest is anti-imperialism. Akinyele Umoja does some of this in his article on Self Defense with his analysis of the Crusader network: https://www.academia.edu/5193708/From_One_Generation_to_the_Next_Armed_Self-defense_Revolutionary_Nationalism_and_the_Southern_Black_Freedom_Movement

Hi Robyn,

Thanks for reading, for the kind words, and for the reference. I would love to hear more about your research and about the material you are working with — please send a message w/your e-mail through the “Contact” (https://www.aaihs.org/contact/) page and the admins can get us in touch.

Best,

-p.

I liked this article too. I an using some Black-Power periodicals for my in-progress dissertation. My first thought about your concern with “the networks, connections and circumstances that helped print culture, and the ideas it carried, circulate” was that an oral history archive might be a good complement to this project. Thoughts?

Hi Kenja —

Thanks for reading, and thanks for the kind words.

I would love to see a skilled oral historian (something I make no claim to being…) track down the people who stood on the corners and sold these and the countless other newspapers that existed at the time. Such a project would not only complement what I wrote here, it would be a necessary component of any thorough research into the topic.

Glad you enjoyed the post…

-p.

“I am using some Black-Power periodicals for my in-progress dissertation.” I apologize for the typo. Additionally, good oral history techniques should yield the narratives of people who stood on the corners and sold newspapers. A few narrators participating in my project reflected on selling “Black News” in New York City.

Yes, this story of Black Power newspapers need to be on every agenda when looking at the era of Black Power.

Thanx for this article. I am an aspiring Newspaper owner myself. And would love to connect with other writers who would like to have their articles read in my small paper. We are seeking to raise the consciousness of our People thru the Newspaper. Many say we should submit to the internet newspaper platform and even though it is powerful. I still believe a physical paper is much more powerful. We must get the paper in our People`s hand so we can reach them,talk to them and build with them outside the internet. Plus the Newspaper can be put up to read for future generations! Yall are onto something. I would like any advice. Anybody who has ran a newspaper your advice or contributions are welcomed! Thanks. My email is geronimocollins@yahoo.com

Peace. Check out my youtube channel youtube/mrgeronimo33