Can Superheroes Be Woke?: Black Liberation and the Black Panther

*This post is part of our new blog series on The World of the Black Panther. This series, edited by Julian Chambliss and Walter Greason, examines the Black Panther and the narrative world linked to the character in comics, animation, and film.

Coinciding with the multi-year production of the Black Panther movie (formally announced in 2013), Marvel hired renowned political commentator Ta-Nahesi Coates to write what would become a highly anticipated and successful run of the comic series (2016-2017). In subsequent and short-lived spinoffs, World of Wakanda and Black Panther & The Crew, Marvel hired well-known writers Roxanne Gay and Yona Harvey to work alongside Coates and develop more narrative arcs for their highly valued, superhero property. Through these hires Marvel signaled their (financial) interest in securing niche audiences with varying levels of investment in anti-racist politics and the concurrent rise of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement.

Given the optimism that swelled around the releases of these comic books, it is clear that there was a sincere belief among readers and writers that superheroes like the Black Panther can “be woke.” In Black Panther & The Crew (2017), this is the very raison d’être given when T’Challa (Black Panther) and Ororo (Storm) ask a veteran civil rights organizer why they have been summoned to Harlem to investigate the murder of a prominent Black activist: “for y’all to wake up.” Yet as Marc Singer argues, any imaginative potential for Black radicalism in this genre needs to be tempered by the fact that “the handling of race is forever caught between the [superhero] genre’s most radical impulses and its most conservative ones.”1

Set against the backdrop of a BLM protest, this particular spin-off offers an excellent case study to test the basic assumption of a “woke” Black superhero against the actual politics of the BLM movement, whose construction and imagination are in no small part indebted to Coates’s own work on police brutality, housing discrimination, reparations, and mass incarceration. Similarities and differences between the two can help answer some crucial questions about the intersection of superhero comics, race, and politics: how effective is the superhero genre as a vehicle for progressive, anti-racist politics? How do the models of justice imaginable through this genre compare with those imagined by current Black liberation activists? Does the very concept of the superhero empower or impede the political imaginary of Black liberation?

Each issue of Black Panther & The Crew chronicles the parallel narratives of Ezra Keith’s construction of a Black superhero team during the civil rights era and the modern-day Crew’s investigation of the suspicious murder of Keith while in police custody.2 Issue #1 offers a glimpse of the potential of the superhero genre in giving shape and form to a radical political imaginary of Black liberation. The narrative opens in the Bronx in 1957. After deploying his superhero team to take down all of the rival crime bosses in New York, Keith confronts the final kingpin, Mr. Manfredi, in his warehouse. After Keith’s team destroys Manfredi’s inventory, he makes a decision uncharacteristic of the genre: he does not take Manfredi to the police. Against a fiery background and buttressed by his muscle-bound superhero team, Keith simply lets Manfredi free: “Go home, Mr. Manfredi. Kiss your wife. Hug your kids. Honor your friends. Love your neighbors. Because I promise you, should you ever threaten my neighbors again . . . the next story they tell will be about you.” A scene-to-scene panel transition immediately transports the reader to modern-day Harlem where a BLM protest has gathered following Keith’s murder while in police custody. Among a host of small, hard-to-read signs with slogans like “Black Lives” and “Justice for Ezra,” one sign stands out in bold, red ink: “NO POLICE.” Side-by-side these scenes suggest that the superhero genre might offer ways of imagining accountability outside of the now-default framework of policing and incarceration.

Specifically, these scenes evoke a practice advocated by BLM activists–such as Mariame Kaba, Mia Mingus, and Barbara Arnwine–called “transformative justice,” defined as “a liberatory approach to violence . . . [that] seeks safety and accountability without relying on alienation, punishment, or State or systemic violence, including incarceration or policing.” Issue #1 suggests that the superhero genre might provide an aesthetic shape and form for conceptual frameworks and social practices circulated and applied among some anti-racist community organizations but that can seem unimaginable to many in the current political mainstream. The fictional space of superhero comics offers at least the potential for a place to visually experiment with imaginative social structures like transformative justice, and to provoke readers with questions of “what if” that easily fit into their expectations of the genre.

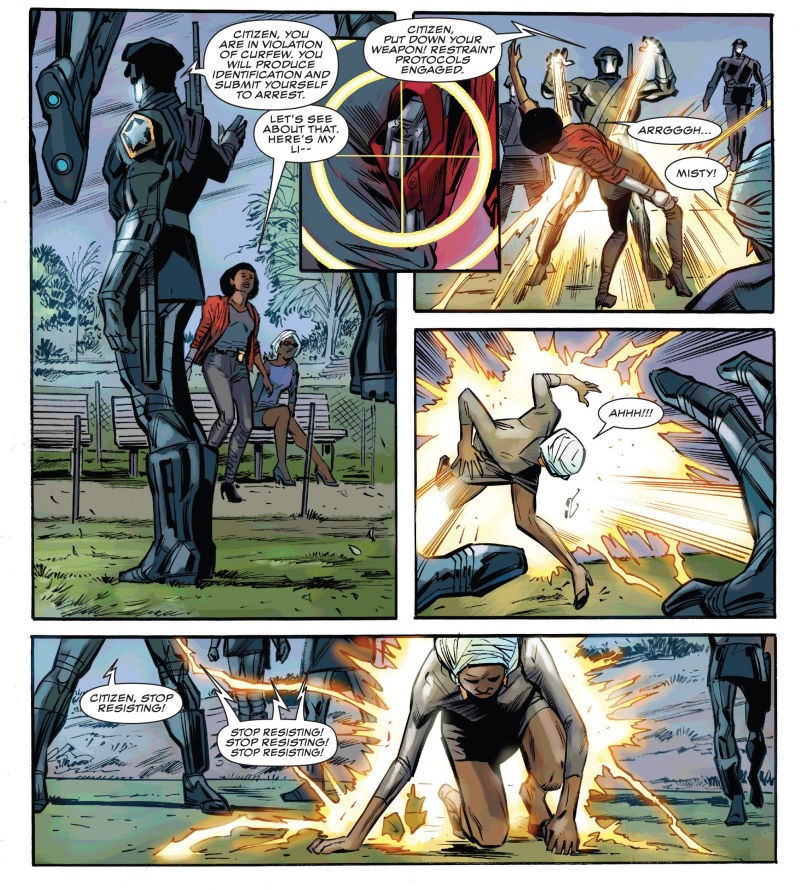

Issue #1 fulfills much of the promise of this narrative frame, exploring how superpowers do not place the members of the Crew outside the realm of racial injustice and terror. Detective Misty Knight becomes disillusioned with the system when her suspicions of corruption are confirmed: the police and correctional officers instinctively, if unknowingly, act to abet and cover-up the still-mysterious murder of Ezra Keith. Afterwards in a scene evocative of ProPublica’s report that software used to predict the likelihood of a person to commit future crimes had a racial bias, Knight and Storm are racially profiled and attacked by mechanized “Americops,” “a mix of Stark tech and counterfeit crap,” while sitting together in a park. As part of a long history of cosmopolitan super-teams who Ramzi Fawaz argues, “offered sustained exploration of the conflict between loyalty to national citizenship and a broader commitment to global justice,” the Crew provides an opportunity to consider the issues of BLM in a national and even Pan-African context. While Misty Knight and Luke Cage are Black Americans directly enmeshed in the systemic racism of US policing, T’Challa (fictional Wakanda), Storm (Kenya), and Manifold (Australia) each confront their own connection to these social forces on the level of not superhero identity but a broader based solidarity through racial identity and oppression.

After the first issue, however, the reader instantly confronts the structural limits of the superhero genre as an aesthetic vehicle for Black liberation. As the parallel historical narrative unfolds across the six issues, the reader discovers that Keith’s super-team betrays the cause of fighting crime and white supremacy, falling in with Hydra, the ur-villain of the Marvel universe. While Keith spends his later years attempting to atone for his involvement by fighting for the cause “the right way,” he ultimately serves as the fall guy in his nephew Malik’s Hydra-funded plot to co-opt the BLM movement, motivated simply out of personal greed. In an escalation of the threats facing the Crew, Malik joins forces with Zenzi, the antagonist of Coates’s previous Nation under Our Feet (2016), whose superpower is intensifying the pre-existing emotions of crowds of people. Because apparently Black protestors’ righteous anger can be easily manipulated—remarkably a framing device not unique to Coates’s series—the protestors listening to Malik’s rhetoric quickly fall prey to Zenzi’s power.3 Marked with possessed green eyes, the BLM protestors break out into violence and prove to be the ultimate villain for the Crew to fight. In a bizarre climax, Cage and Knight beat, kick, and body slam BLM protestors into Manifold’s magical transports in an effort to disperse the crowd, while Storm simultaneously electrocutes the Americops who are also committing violence against the protestors.

The distrust of bottom-up Black liberation movements like BLM—organically initiated by three women of color using a hashtag on social media no less—is not limited to Black Panther & The Crew. Recent widespread hand-wringing over Russian bots creating fake “Blacktivists” on Twitter and Facebook and Russian-funded Black self-protection classes serves as examples of a longstanding fear of what may be if Black grievances are not shepherded through trusted leadership and hierarchical gate-keeping institutions. While Coates’s body of work displays no evidence of these attitudes, quite the opposite, these bias fit all too comfortably within the logics that govern the superhero genre. When asked about how the BLM movement influences his writing, Coates offers a mixed response that suggests what is inherently limiting about the superhero genre: “It becomes clear in the first issue that the activist is not just an activist. There’s something more going on there.”

As the racial injustices that stage the narrative become entwined in the larger evils in the Marvel universe, the power to resist and overturn these social structures ultimately belongs to superheroes alone. In the denouement of the story, the Crew renews their commitment to fight for the city that abstractly binds them, as Luke Cage shouts the titular phrase, “We are the streets.” Yet this “we” quite clearly excludes the BLM protestors represented as too unpredictable and too easily frenzied by simple rhetoric.4 For this very reason, Black Panther & The Crew ultimately cannot effectively imagine the collectivity necessary for Black liberation. It remains up to BLM activists alone to organize and fight against a villain untranslatable to the superhero genre: widespread, diffuse, and ordinary white supremacy.

- Marc Singer, “Black Skins and White Masks: Comics Books and the Secret of Race,” African American Review 36.1 (2002): 110. ↩

- Keith is inspired to organize the group of heroes during the Asian-African Conference in Bandung, Indonesia, 1955. ↩

- See Episode 10 of Marvel’s Netflix series Luke Cage. ↩

- These qualities are the very antithesis of the reasoned and intellectual Illuminati member, Black Panther. ↩

If ordinary life and living are translatable to the superhero genre then there will arise a Superheros like none ever imagined. They will possess the cunning, strength and unlimited tenacity required to effectively counter each of its strengths and exploit its weaknesses. Never wavering, keenly aware of all its forms, tactics co-conspirators and absolutely WILL destroy all its forms including the root, spores and alternative forms.