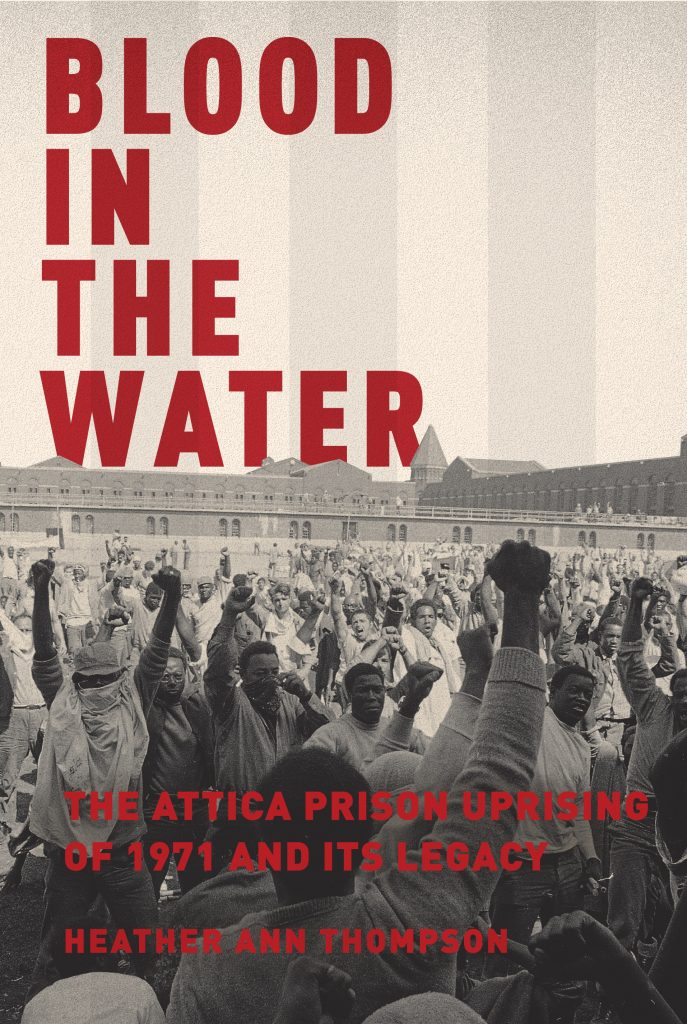

Blood in the Water: A New Book on the Attica Prison Uprising

Today is the beginning of our online roundtable on Heather Ann Thompson’s new book, Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. Professor Thompson is an award-winning historian at the University of Michigan. She has written on the history of mass incarceration, as well as its current impact, for several outlets including The New York Times, Time, and The Atlantic. Thompson is also the author of Whose Detroit?: Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City and editor of Speaking Out: Activism and Protest in the 1960s and 1970s. Along with Rhonda Y. Williams, Thompson edits a book series for UNC Press, Justice, Power, and Politics, and is the sole editor of the series, American Social Movements of the Twentieth Century published by Routledge. Follow her on Twitter @hthompsn.

We begin with introductory remarks from Michael Ezra, editor of the Journal of Civil and Human Rights. Today, Kali Nicole Gross will survey Thompson’s attention to trauma in Blood in the Water. On Monday, Dan Berger will describe how Thompson’s work relates to the ever expanding archive of the carceral state. On Tuesday, Danielle McGuire will place the events at Attica and Thompson’s work within a legacy of resistance. On Wednesday, Robert Chase will connect the Attica Prison Uprising to a broader political movement. On Thursday, we will feature posts from LaShawn Harris and Russell Rickford that consider the legacy of the Attica Prison Uprising through two different lenses. On Friday, Heather Ann Thompson will offer a response.

It feels good to introduce such a wonderful book, which has rightfully been acclaimed by the reviewers whose work you will read over the next week as part of this Black Perspectives roundtable, co-sponsored by the Journal of Civil and Human Rights. Usually I choose not to tackle academic books of long length, because they tend to bore me after a while. Some of these books—winners of major prizes that are academic favorites assigned to generations of graduate students—actually set a quite-poor example of how to write history. Such works can become unworthy standard-bearers, unfortunately, that are capable of misleading people into thinking wrongly about what is good writing and presentation.

Despite all of its acclaim—a movie contract, brisk sales figures, end-of-the-year “best book” lists, a National Book Award finalist, multiple write-ups in the New York Times, television interviews with the author—and despite my longtime admiration for Heather Thompson’s work and career, I admit that I was still reluctant to read Blood in the Water because of its length. My mistake. This is the rare long work of non-fiction that remains a page-turner all the way to the end. I was supposed to get tired of this book and never did.

Blood in the Water is a tribute to the tenacity and determination of a historian who not only found a way to unravel a narrative whose most important elements deliberately were hidden from view by white men of power, but also to render the story readable so that even a middle-school student could understand in full Blood in the Water’s storylines. Some of the reviews in this roundtable note the book’s practical considerations, and I think they should be mentioned here: outstanding editing, crisp prose, and crystal-clear organizational structure characterizes every page and section of this work. The very long and complicated story of the Attica rebellion and its aftermath needs at least five hundred pages to be told. Nothing in the book seems superfluous; it may be heavy but it is by no means fatty. It is a pleasant reminder that you don’t need to bore the heck out of your audience even as you drill ever deeper into the archives.

Perhaps the greatest strength of Blood in the Water, which actually might provoke criticism that I would like to address preemptively, is the author’s willingness to sacrifice explicit analysis in order to make the narrative readable and accessible to a more widespread audience. The narrative-to-analysis ratio is the book is perhaps 95 percent, and it would be fair to argue that there is no coherent thesis or guiding principle or argument, except that Blood in the Water is most certainly the definitive account of the Attica uprising and its legacy.

But I applaud the author and the editors for not jamming further complication into a narrative whose implications are self-evident. You do not need the author to tell you explicitly who was corrupt, who fought for justice, where the system failed, and who was negligent. All of that is baked into the narrative and organizational structure of this masterwork. It would be wrong to downgrade the historian for her ability to deftly handle material that is all too often ham-fistedly served up to readers as stand-alone “analysis” set apart from the narrative.

Although many are written as if they were, books are not dissertations—as an author you do not need to show the reader everything you know and how smart you are. I ultimately see the author’s choice to privilege narrative as the product of her courage to trust readers to draw whatever conclusions they may, based on an impressively researched and written account that takes into balance as many sources as possible. Given the depth of her study, the author would have easily been able to riff on every last meaning. Thus she should be applauded for having the discipline to suppress her own first-person voice on a subject that she obviously cares about deeply.

From reading Blood in the Water I got the sense that Attica was the Hurricane Katrina of its day, a completely avoidable national embarrassment with such abhorrent racial overtones and catastrophic outcomes that many people simply wanted to deflect attention away from it or deny its importance. By shining a light on what happened, despite her investigation being actively sabotaged, and by presenting the material in a way that will help people want to learn about it, Heather Thompson has helped move our culture a hair closer to being one that further respects civil and human rights. Read this great book and assign it to your students and you will not be disappointed.

Michael Ezra is Professor of American Multicultural Studies at Sonoma State University and editor of the Journal of Civil and Human Rights. He is the author of Muhammad Ali: The Making of an Icon and Civil Rights Movement: People and Perspectives and editor of The Economic Civil Rights Movement: African Americans and the Struggle for Economic Power. His next book, co-edited with Carlo Rotella, The Bittersweet Science: Fifteen Writers in the Gym, in the Corner, and at Ringside will be published by University of Chicago Press in April. Follow him on Twitter @civilhumanright.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.