Black Power in Papua New Guinea

The Black Power Movement stretched across the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific ocean worlds in both expected and surprising ways. Scholarship on Black Power in Oceania has largely focused on Australia and New Zealand. My own work centers on Black Power in Melanesia, where the Movement was very much linked with the region’s surges for decolonization and Black self-determination. This was certainly the case in Papua New Guinea, where, in the 1970s, self-determination in the mineral-rich island represented the tangible potential of Black liberation in Oceania.

Denounced as a “Mau Mau factory” by its detractors, the University of Papua New Guinea (UPNG) was a beacon of Melanesian transnationalism during the country’s push for independence from Australia. Beginning in 1967, the University hosted a series of popular Waigani seminars that addressed Melanesian issues, including economics, politics, culture, education, history and land tenure. Across the 1970s, the campus was influenced by various movements such as Josephine Abaijah’s Papua Besena movement and the Bougainville uprisings. In addition, UPNG students actively engaged the ideas of Africana political thought and African liberation struggles.

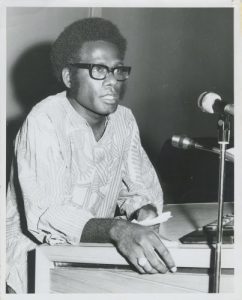

In 1970, in the morning hours of one of many “anti-colonialist hate sessions,” UPNG students formed the Niugini Black Power Group (BPG). According to co-founder Leo Hannett, the BPG was a Frantz Fanon-inspired African Negritude movement. The group calibrated the ideas of Black Power and Negritude to address the specific concerns of Papua New Guinea. Some students and colonial administrators claimed that Black Power was dangerous and unnecessary in ‘Niugini,’ where the population was majority-Black.

However, Hannett asserted that the Movement was as “relevant to Niugini as a betel nut,” referencing the country’s long standing popular cultural practice of chewing the red nut. The phrase ‘Black Power’ gave the philosophy of self-determination its “ginger, pepper and limestuff.” In this case, blackness represented more than phenotype, and served as a reference to culture, social, and religious values. In Papua New Guinea, Black Power was an essential part of nation building.

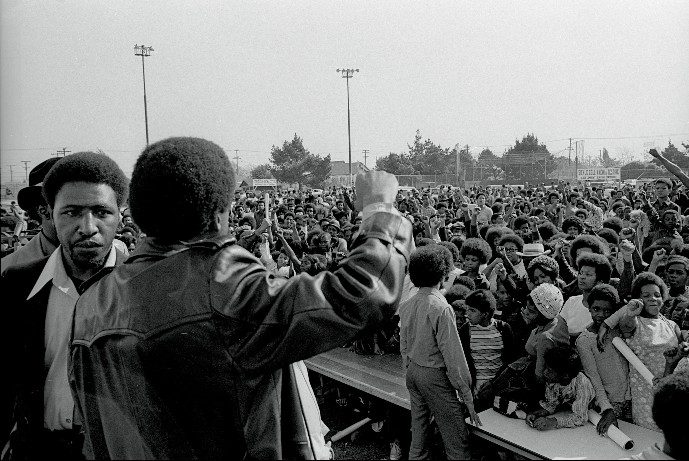

The BPG’s transnational and international concerns addressed the need for self-determination. The group challenged Australian colonialism, segregation, the exploitation of Papua New Guinea’s mineral resources by multinational corporations, Indonesian imperialism in West Papua, and a Public Order Bill that restricted the public’s rights to demonstrate but simultaneously increased police power. The group drew inspiration from a range of Black activists across the African Diaspora and the global south. This included the works of Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, Kwame Nkrumah, Paulo Freire, Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton. It held demonstrations, lectures, and debates on Black Power, and its members published articles in the UPNG’s student newsletter, Nilaidat.

In 1971, the Niugini Black Power Group (BPG) submitted a proposal to a United Nations Visiting Mission to Papua New Guinea. The document called for self-government, people’s control of all of Niugini’s mineral resources and a Black Niugini program to match Australia’s “whites-only” immigration policies. For its part, the UN’s Afro-Asian bloc pressured Australia to set dates for self-determination in Papua New Guinea, which it felt was “becoming synonymous with conditions in Rhodesia, South West Africa, and Portuguese Mozambique and Angola.”1

The BPG included a core of nationalist artists who studied literature with UPNG Professors Prithvindra Chakravarti and Ulli Beier. Of German-Jewish descent, Beier taught Creative Writing and had previously lectured at Nigeria’s University of Ibadan. Supported by his relationships with Africana writers, this collective read Wole Soyinke, Chinua Achebe, Leopold Senghor, and Negritude’s Presence Africaine. They produced memoirs, novels, poetry, plays, and short stories in English, indigenous languages, and Pidgin. This included Kumulau Tawali’s “Bush Kanaka Speaks” and Albert Maori Kiki’s Ten Thousand Years In a Lifetime. In publishing journals like Kovave, Papua Pocket Series, and Papua New Guinea Writing, these artists became global conduits of Melanesian transnationalism. This was significant. While Western media outlets such as Time, National Geographic and Life magazine described Papua New Guinea as a relic of the Stone Age, UPNG artists constructed a version of Black Pacific modernity. Indeed, Papua New Guinea reflected the future—rather than just an ancient past—of the Black Pacific in terms of its discourses on race, historical awareness, and burgeoning political sovereignty.

These writers included BPG member John Kasaipwalova, whose poetry invoked African Diasporic ideas of liberation. His book, Reluctant Flame, called for the fires of Niugini nationalism to “take fuel from brother struggles” and Black uprisings in South Africa and the United States. A self-described Black nationalist, he was arrested in Brisbane, Australia in 1970 during a demonstration in support of Bougainville. He challenged Black writers to capture and express the people’s consciousness by breaking the colonial mentality of Black people.2

The influence of Black Power was evident in the works of individuals like Arthur Jawodimbari, a dramatist who completed a degree in English literature from UPNG in 1972. He studied popular theater and, in 1974, toured Japan, Ghana, Nigeria, and the United States for several months. In Nigeria, he spent time with artists such as Duro Ladipo (University of Ife Theatre) and Obi Egbuna. In Ghana, he sat with playwright Efua Sutherland. He continued to Harlem, where he visited Barbara Ann Teer’s National Black Theatre. Jawodimbari used these experiences to develop popular theater in Papua New Guinea, which he used “as a medium of expression, liberation and education.”3

Australian literary journals published Papua New Guinea writing as expressions of the global south. Fiji’s University of the South Pacific (USP, Suva) prominently displayed the works of UPNG artists like Jawodimbari. Hence, Melanesian art, scholarship, and literature helped to transform the UNPG campus into a hub of political promise that drew students, scholars, and activists from across Oceania. This included activists like Claire Slatter and Vanessa Griffen, who organized Fiji’s monumental 1975 Pacific Women’s Conference. As students at USP, Slatter and Griffen were actively involved in the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific Movement (NFIP).

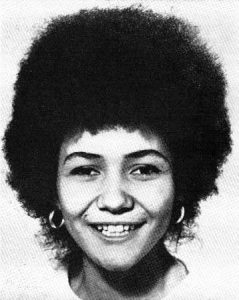

In 1972, Bobbi Sykes wrote to Kasaipwalova during her tenure as UPNG’s Student Representative Council (SRC). One of Australia’s more iconic Black Power personalities, Sykes sought assistance from UPNG students in raising international interest about the Black struggle in Australia. Having visited New Zealand to examine the Māori situation, Sykes subsequently visited UPNG under the invitation of the SRC. Representing the Aboriginal Canberra Tent Embassy, she gave talks about Australian apartheid at the Papua New Guinea Institute of Technology. Australia’s Secret Intelligence Organization (ASIO) nervously noted these connections.4

The Niugini Black Power Group is a clear example of Black Power’s reach in the Oceania. Scholarship on Africana history continues to cross Atlantic borders of time and space to include the Pacific as a region of critical discourse on race, gender and protest. As an expanding body of scholarship suggests, Black Pacific Studies is fast growing as a critical subfield of Africana scholarship. This is a welcome trend.

- Leo Hannett, “The Niugini Black Power Movement,” in Tertiary Students and the Politics of Papua New Guinea (Lae: Papua New Guinea Institute of Technology, 1971), UPNG Library, Papua New Guinea Collection, Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea; Merz Tate, “Administration of Papua & New Guinea,” Box 219-8, Merz Tate Papers, Moorland Spingarn Research Center, Howard University. ↩

- Post Courier, 28 January 1970; Interview with John Kasaipwalova, 27 August 1970, Australian Secret Intelligence Organization (ASIO) files, A452 1970/524, National Archives of Australia (NAA). ↩

- “Arthur Jawodimbari,” Papua New Guinea Writing 13 (March 1974): 12. ↩

- “Bobbi Sykes to UPNG Students Association,” “Bobbi Sykes,” 17 May 1972, “Aboriginal seeks PNG support,” 7 July 1972, Roberta Sykes, Vol. 1, ASIO, NAA ↩

Congratulation brother