Black Nationalist Women’s Political and Intellectual Labor

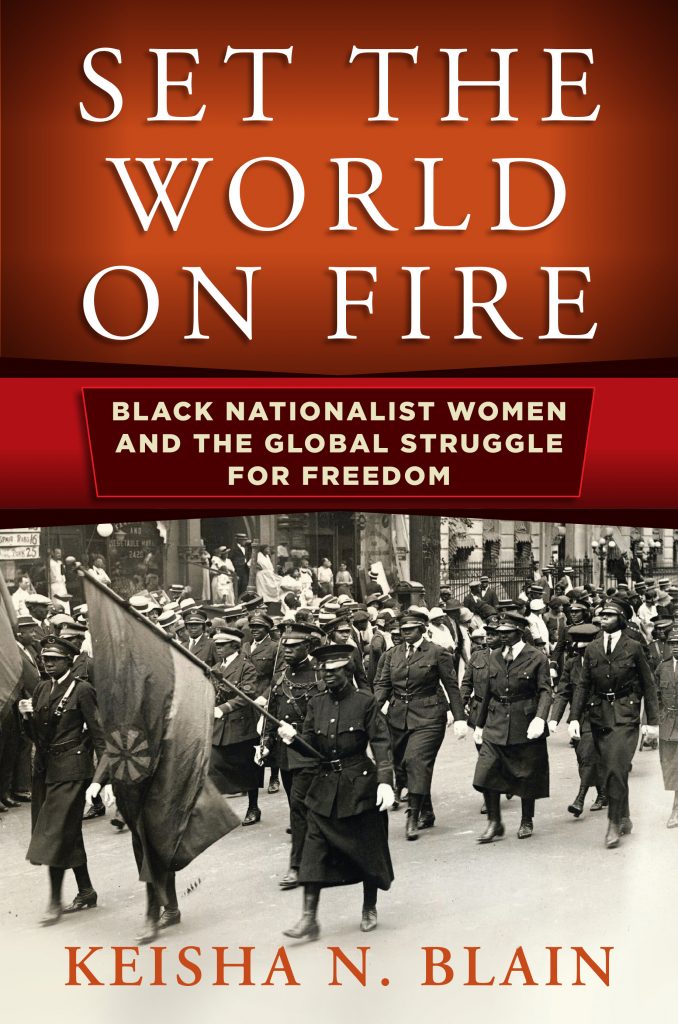

*This post is part of our online roundtable on Keisha N. Blain’s Set the World on Fire

How does our historical understanding of Black nationalism shift if we foreground the aspirations, organizing strategies, and intellectual labor of working class Black women? How can centering the work of Black nationalist women provide a means to rethink how we demarcate the rise and fall of Black freedom movements and how we understand the ruptures and continuities between the struggles of prior generations of activism and the ongoing pursuit of Black liberation?

These are just some of the questions that animate Keisha N. Blain’s prodigiously researched Set The World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom. Moving in and between cities and towns in the North, South, and Midwest as well as in locales in Jamaica, England, and West Africa, this book takes readers into the lives and political work of Black women who shaped and remade Black nationalism to fit a range of agendas in a period marked by Jim Crow’s regime of disenfranchisement, worldwide economic depression, global warfare, anti-colonial coalition building, and the prevalence of a patriarchal social order that reserved little space for Black women to publicly occupy positions of leadership and authority. This is the world in which women like Amy Ashwood Garvey, Amy Jacques Garvey, Henrietta Vinton Davis, and Mitte Maude Lena Gordon developed what Blain describes as an “idiosyncratic political praxis born out of necessity” steeped in Black nationalist ideals including, but not limited to, racial separatism, Pan-African unity, anti-European colonialism, racial pride, and economic empowerment (4). In doing so, they created spaces for Black women to lead, voice their “freedom dreams,” and pursue strategies with unlikely allies that drew other Black working class men and women to internationalist movements designed to secure rights, claim resources, and make demands of the state on behalf of the liberation of Black people in the US and across the Diaspora.

One of the major historiographical interventions that Blain makes is to push scholars to rethink how we orient twentieth century histories of Black nationalism in relation to Marcus Garvey and the successes and failures of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Rather than fracturing a US-based Black nationalist movement following Garvey’s deportation, Set the World on Fire demonstrates that his departure—and the leadership void that it left within the UNIA—engendered the very conditions that ultimately catapulted women including Amy Jacques Garvey and Henrietta Vinton Davis into formal and informal positions of greater influence within the organization and beyond. Moreover, Blain writes against the grain of conventional assessments of Black nationalism’s significance, which typically concentrate on the interwar Garvey movement and the emergence of a modern Black Power movement during the late 1960s and early 1970s with no critical attention paid to what happened in between. Instead, blending engaging analysis with attention to descriptive storytelling, Blain’s narrative departs from male-centered depictions of Black nationalist praxis and introduces readers to the women whose organizational networks, movement-building strategies and visions for Black freedom sustained Black nationalist currents from the 1930s up through and including the civil rights era of the 1950s.

In uncovering these stories, she is careful to note that while the UNIA and the social, political, and ideological networks that fueled it often served as an entry point for Black women including Maymie De Mena and Casely Hayford to gain a platform and garner the political capital necessary to advance their agendas, the trajectory of their work transcended Garveyism in ways that allowed Black nationalism to remain a viable tool for mobilizing communities to confront white supremacy throughout the twentieth century. In the vein of recent work by Ula Taylor, this particular point underscores how reductive treatments of interwar Black nationalism narrowly focused on (Marcus) Garveyism and its adherents obscures the various permutations of this political philosophy that the women in Blain’s study adapted and remade to their own ends.

A significant portion of the book traces the activist work of Mitte Maude Lena Gordon and the development of the Peace Movement of Ethiopia (PME), which became the largest organization in the US espousing Black nationalism founded by a woman. In addition to chronicling Gordon’s early political formation—from the lessons she received from her father about the Bishop Henry McNeal Turner’s repatriation plans to her confrontations with the everyday realities of economic hardships and violence marking Black life in Jim Crow America—Blain underscores why someone like Gordon found solace and inspiration in the UNIA’s message of Black autonomy, self-sufficiency, and diasporic belonging. In detailing the ideological bearings that shaped the establishment of the PME, Blain shows that Gordon drew from an eclectic reservoir of Black nationalist currents associated with the UNIA’s “race first” ideals, the teachings of the Moorish Science Temple, as well as religious symbols and sacred texts of Islam and Christianity. Against the backdrop of the economic turmoil caused by the Great Depression, which only exacerbated the precarious status of working class Black people, the PME transformed the pursuit of repatriation to Liberia into its central calling card to recruit members and build a political base that extended from Gordon’s home in Chicago to locales in Mississippi and Florida. As a result, Blain positions the PME as a type of relay point that facilitated how residents of Chicago’s “Black Belt” joined forces with sharecroppers in the Mississippi Delta to articulate an internationalist response to their shared fate of living in a nation where the logic of white supremacy remained foundational to the legal, political, economic, and social structures that conditioned their second-class citizenship. Ultimately that response entailed petitioning the federal government to provide the resources to emigrate to Liberia, a place that they imagined as a refuge and a site for creating alternative and autonomous Black futures.

Blain notes that it was actually the petition that Mitte Gordon mailed to President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933 on behalf of the PME with some 400,000 signatories requesting federal relief to finance the resettlement in Liberia that initially drove her interest in studying Gordon’s life and work. In drafting the petition, PME members rooted their claims in the promise of FDR’s New Deal rhetoric which aimed to mobilize federal resources to provide public assistance to address widespread economic insecurity and social dislocation during the Great Depression. As we now sit three decades out from Harvard Sitkoff’s now classic study exploring how New Deal era politics laid the foundation for postwar civil rights struggles, Blain’s examination of the PME provides an important object lesson for understanding how working class Black Americans outside of mainstream organizations like the NAACP made sense of what the New Deal could mean for them in ways that foreshadowed the demands that future generations would make of the welfare state. She explains that in crafting their petition for emigration funding, PME signatories leveraged their constitutional rights as US citizens to advance a transnational agenda that involved taking their visions for Black freedom elsewhere to fulfill that which should have been guaranteed by their American citizenship.

PME members made a case to FDR for federal support of emigration on two central premises that came to define how Black nationalist women including Celia Jane Allen and Amy Jacques Garvey would frame the rationale for federal legislation in support of resettlement in Liberia for nearly two decades. First, they asserted their rights as citizens to participate in the promise of a New Deal even as policies like the Social Security Act of 1935 explicitly denied benefits to segments of the working classes where Black Americans were overrepresented as domestic and agricultural laborers. Additionally, PME members interpreted their version of New Deal relief as a form of redress that could serve to acknowledge how their relationship to the economy and their wider aspirations for freedom were corrupted by the long and extant shadow of slavery and Jim Crow. Although FDR rejected Gordon’s petition, years later when Theodore Bilbo, an avowed white supremacist, introduced the Greater Liberia Bill in the U.S. Senate, in pledging her support for the bill and as a means of gathering supporters across the diaspora to draw a line between the bill’s content and its congressional backer, Amy Jacques Garvey adopted a similar argument insisting that federal aid to Black Americans for repatriation amounted to a “small amount of recompense for services rendered during slavery” (159).

Blain concludes her narrative by detailing the various tentacles of Black nationalist women’s political and intellectual labor that extended from the interwar period and served as the “ideological bedrock” for philosophies that would come to define the modern Black Power movement. Yet the women at the heart of her narrative and the agendas that they promoted also reveal how the legacy of twentieth century Black nationalism is tethered to ongoing debates about reparations and the ways in which Black people in different parts of the world continue to make demands of institutions and the various arms of the state based on a belief that resources should be (re)distributed to reckon with and ameliorate the persistence of inequities rooted in histories of enslavement. In this regard, Blain’s work not only secures its place in the historiography on Black nationalism based on its ability to introduce historical actors who have oftentimes been obscured by the organization of knowledge, but also by its capacity to illuminate the connections between past and present.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.