Black Nationalist Women’s Global Visions of Freedom

*This post is part of our online roundtable on Keisha N. Blain’s Set the World on Fire

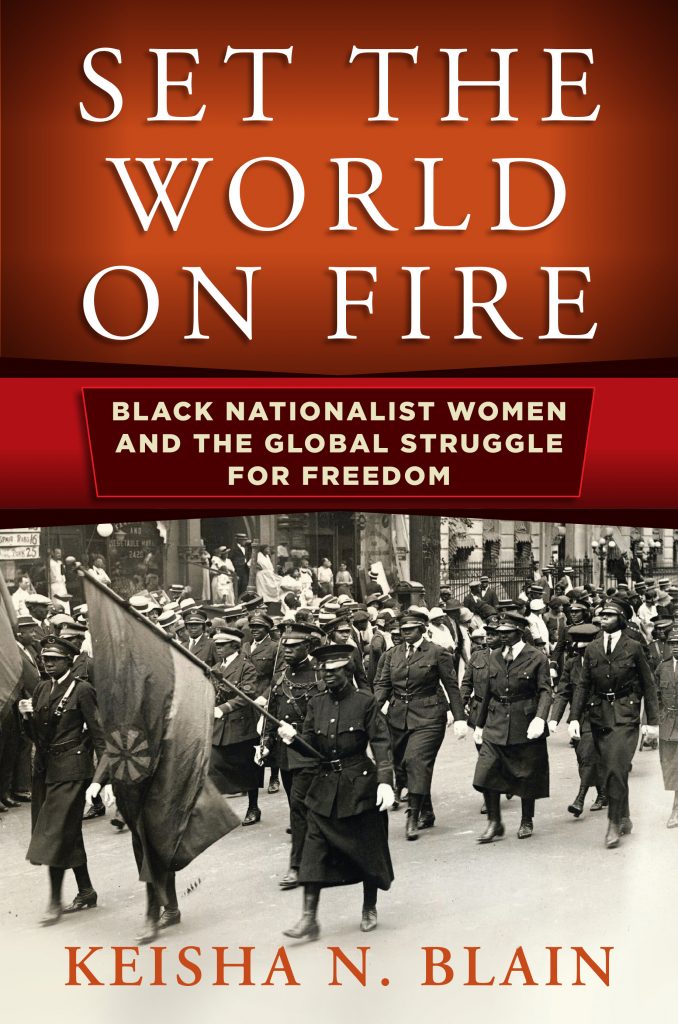

A welcome addition to the library of scholarship on Black women and activism, Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom takes its title from an article by Josephine Moody of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) Cleveland chapter titled “We Want to Set the World on Fire.” According to Blain, that article called for an immediate overthrow of “the global white power structure in order to achieve universal Black liberation” (136).

This goal remains a consideration of many who continue to face the effects of this white power structure. The assertion that this white power structure is global animated a global struggle for freedom throughout the 20th century that continues into the 21st century. Such a position was fundamental to the thinking of W.E.B. Du Bois, who Robin D.G. Kelley quotes as title to his article, “‘But a Local Phase of a World Problem,’ Black History’s Global Vision, 1883-1950.” The vision of a range of Pan-Africanists from 1900 onward, it would also run through the UNIA, philosophically, even as the organization and its members worked on particular local and national issues. Amy Ashwood Garvey, the first wife of Marcus Garvey, is also quoted by Blain as offering a similar articulation: “The Negro question is no longer a local one, but of the Negroes of the world, joining hands and fighting for one common cause” (18).

Set the World on Fire is an affirmative rearticulation of Josephine Moody’s position frontally affirming the role of women in this global struggle. It joins a growing body of work, each one providing an important piece of detail as we put together the full picture. In Radicalism at the Crossroads: African American Women Activists in the Cold War, Dayo F. Gore provides the Black Left intersection and argues that before the Civil Rights/Black Power period, Black women consistently organized in a number of ways. Keisha Blain’s Set the World on Fire documents the activities of women throughout the 1920s into the decades after Garvey/UNIA ascendancy. Organized into six chapters accompanied by an introduction and conclusion, the book begins with a chapter on “Women Pioneers in the Garvey Movement,” which covers well documented material on the women who helped make the UNIA an international organization. Blain identifies Amy Ashwood’s participation, as a “cofounder and first secretary”(14) of the UNIA from its beginnings in Jamaica as fundamentally critical to shaping the women’s platforms in the UNIA. Amy Ashwood’s Black consciousness had preceded her 1914 meeting with Garvey and together they developed the organizational techniques for delivering a mass movement. Throughout this chapter, as well, is the discussion of women already recognized by those familiar with the subject as central to the UNIA’s early development in Harlem. The classic photographs of UNIA’s Black Cross Nurses and the African Motor Corps have additional impact as we read about their functions.

Significantly, one of the tensions that women felt in UNIA was the struggle with male dominance. Blain sees several of them as having “protofeminist views and praxis,” often wavering between feminist and nationalist ideals, articulating a critique of Black patriarchy while endorsing traditionally conservative views on gender and sexuality” (36). The work of Amy Jacques Garvey, for example, in maintaining the organization along with and after Garvey’s incarceration is relevant and was earlier evident in the women’s page of the Negro World, which she edited.

One of the critical contributions of Set the World on Fire is the role of women’s leadership in the issue of emigration. Mittie Maude Lena Gordon is a representative activist in this regard. From a base in Chicago she created the Peace Movement of Ethiopia (PME) and became a well recognized public street orator on a range of Black issues. There is also an interesting intersection with Gordon’s development of the PME and the kind of peace work that Black Left women like Claudia Jones would undertake—though from divergent political positions. Interestingly as well, Gordon was arrested in 1942 on charges of sedition and conspiracy, and incarcerated in 1944. She served two years in the Federal Reformatory for Women in Alderson, West Virginia, as a political prisoner, a decade before Claudia Jones was sentenced there in 1955.

The UNIA remains the primary organization for Black empowerment in the early years of the 20th century. But putting the PME into the picture allows us to see additional continuities as well as disjunctures. For example, Celia Jane Allen organized for PME in Mississippi in the 1930s and 1940s by collecting signatures of Black people who wanted to return to Africa. Because of her roots in Mississippi and her familial connections, she was able to network through local ministers and their churches to do an impressive amount of PME organizing. Queen Mother Moore’s activism intersects with Black Left work and women’s organizing projects that spanned the entire South to North spectrum. Allen and Moore put into context the activism of Fannie Lou Hamer in the 1960s; Allen and Moore provided the kind of platforms on which subsequent movement work could be built. The global impact of post-UNIA organizing in places like Jamaica by Una Marson and Amy Bailey is significant as well. One sees a definite diasporic circulation in their various moves to England, which would become another site of political organizing around migration to Africa.

In Set the World on Fire, Blain provides the detailed historical research needed for making connections in the interpretation of diasporic social movements throughout the twentieth century. She allows us to put in context work like Robyn Spencer’s The Revolution Has Come: Black Power, Gender, and the Black Panther Party in Oakland, which deals with subsequent freedom struggles. Above all, Blain presents us with incontrovertible evidence of Black women’s leadership in Black political struggles at critical junctures with, without, and in spite of consistent masculinist approaches to organizing.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.