Black Childhood and the Freedom to Play

The following is a guest post from Dr. Janaka Bowman Lewis, Assistant Professor of English at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Her monograph Civil Discourse: Black Women’s Narratives of Freedom and Nation, will be published by McFarland Press. Her current research project, “Lessons in Freedom,” also examines what black students were taught about the regulations of their behavior coming out of enslavement in the nineteenth century. Future research continues the conversation of what was taught to black students into the twentieth century. She is also a children’s book author of Brown All Over (2012) and the proud parent of a kindergartener and a preschooler. Dr. Lewis works with community organizations and with elementary schools on using African American literature to talk about diversity with children (noting also what it means to be a child in America with the freedom of (or limits placed upon) movement and access to social spaces.)

The following is a guest post from Dr. Janaka Bowman Lewis, Assistant Professor of English at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. Her monograph Civil Discourse: Black Women’s Narratives of Freedom and Nation, will be published by McFarland Press. Her current research project, “Lessons in Freedom,” also examines what black students were taught about the regulations of their behavior coming out of enslavement in the nineteenth century. Future research continues the conversation of what was taught to black students into the twentieth century. She is also a children’s book author of Brown All Over (2012) and the proud parent of a kindergartener and a preschooler. Dr. Lewis works with community organizations and with elementary schools on using African American literature to talk about diversity with children (noting also what it means to be a child in America with the freedom of (or limits placed upon) movement and access to social spaces.)

***

A recent media post by a colleague lamented his sentimental response to seeing black kids at play. He wondered if he was being overly sentimental, and responses assured him that he wasn’t because it is no longer something we see or recognize on a regular basis I responded that maybe they were tears of “justice” at seeing children claim something that should be their right—their time and their space. I know that “play” is perceived differently by different positions of authority. Twelve year old Tamir Rice was “playing” with a toy gun in Cleveland when he was shot by police. Yet, we read stories of white children carrying real guns in public places without penalty. This is not to suggest that they don’t have the right to “play” with BB and pellet guns, but where is the division between who is “playing” and who is a threat? Similarly, when we look at interactions between young brown girls specifically, we see increased penalties in punishment for movement (dancing is not sitting still) and expressive behaviors such as “eye rolling” and shoulder shrugging before we even get to physical contact, represented in books such as Monique Morris’s Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools. Is it size that determines who can play? Gender? Is it race and ethnicity? What is, to use African American vernacular, “playing” too much?

Scholarship of freedom and play has long been shaped for me by a quote from Anna Julia Cooper’s A Voice from the South (1892) that “We look back, not to become inflated with conceit because of the depths from which we have arisen, but that we may learn wisdom from experience” (27). For children who learned the lessons of slavery before seeking or gaining emancipation, I ask, what and where were the circles and sites in which they learned about adulthood, and for girls specifically, how were they able to celebrate girlhood? I am finding that the answers are often through play—unregulated, informal stints of freedom that, once witnessed, could not be unlearned.

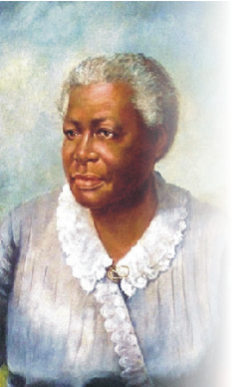

Arguing that “we can give ourselves,” Cooper writes black women into conversations of racial “uplift,” but she is as concerned with past efforts of racial progress as with future opportunities for black men and black women (281). After claiming her freedom, Lucy Craft Laney went on to start the first black kindergarten and the first nursing school for black women in Augusta, Georgia, in addition to a very reputable school called Haines Industrial and Normal Institute in 1886 that was recognized by both W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington. Through speeches and essays, Laney also reflected on the distance from which blacks had come in just a short period of freedom and instructed mothers on how to build their children up at home to be successful and productive as the first generation of free adults. By setting up both personal narratives and ideals of social progress as curricula for life, Cooper and Laney argue for education and institutional opportunities as means for women (and in effect, men as well) to achieve real social progress.

Published around the same time, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s Iola Leroy (1892) is historical fiction that highlights post-Emancipation issues such as the reconnecting of families, but more generally, what black people should do “on the threshold of a new era.” (271) In protagonist Iola’s decision to “teach in the Sunday-school, help in the church, [and] hold mothers’ meetings to help these boys and girls to grow up to be good men and women,’” (276) Harper’s text represents the virtues of education and also proof of how black women can be instrumental race leaders. 1

For children, sacrifice and education are the means articulated in Harper’s fiction to eventually assume the responsibility of racial leadership. In addition to teaching and mentoring such noted educators as Mary McLeod Bethune, Laney also taught John Hope, who became first black president of Atlanta University in 1929, in Augusta, Georgia. After participating in Du Bois’s Atlanta University Conferences, Farmer’s Conferences in Tuskegee that began in 1890 (which became the Hampton-Tuskegee Negro conferences and were concentrated in rural communities), and becoming active in the National Association of Colored Women, organized in 1896, she was eventually invited by Du Bois to the Amenia Conference in 1916 (which she described as an “interracial conclave of leaders assembled to discuss future of the race).”

Her report to the First Atlanta conference in 1896, “Causes of Excessive Mortality: Poverty,” described conditions of blacks under city ‘settlements’ as “mothers working extensive hours and fathers laboring for little pay, with both denied opportunities for decent employment.” 2 Laney addressed the problems of parents who were employed outside of the home and still unable to provide sufficient time or financial resources for their children, but she also offered solutions. At the Second Atlanta Conference, Laney presented topics such as “Mothers’ Meetings,” “Need of Day Nurseries,” and “Need of Kindergartens” to the Women’s Meeting attendees. Laney also endorsed the idea in the conference of “day nurseries” for children while mothers worked, which likely led to her establishment of the first kindergarten for black children in Georgia.

The work with which she challenges black women as they move ahead as free people and into the twentieth century was to teach young children: “Negro women of culture, as kindergartners and primary teachers have a rare opportunity to lend a hand to the lifting of these burdens, for here they may instill lessons of cleanliness, truthfulness, loving kindness, love for nature, and love for Nature’s God.” Although rhetoric of African American uplift had been heard in other narratives by the time of Laney’s speech, the morals she encourages black women, especially teachers, to instill, set a precedent for the progress of an entire younger generation. If these women “of culture” can “daily start aright” these children, they can put them on a strong educational path and prevent them from succumbing to crime.

In her own childhood, both parents provided income, and Laney learned to read with her mother while her father became ordained in the Presbyterian church in Macon. As an adult, Laney promoted black control of schools in addition to homes, control which depended on access to education.

The Red and Black yearbook of 1923, a copy of which still remains intact at the Lucy Craft Laney Museum in Augusta, lists the topics taught between primary grades and high school as Latin, English, History, Bible, Bookkeeping and Stenography, Science, Dramatics, French, Sewing, Teachers Training, and Music. School activities cited in the annual include Declamation, a pageant, a play, Junior-Senior reception, Baccalaureate, recitals, and oratorical contests. Only years removed from an enslaved status herself, a formally educated Lucy Craft Laney analyzes the hindrances of Negro families from reaching their full potential and prescribes the women, especially in the role of teachers of young students, as the answer to instilling right moral guidelines. In the Report of the Hampton Negro Conference in July 1899, she metaphorically reconstructs a scene in which from a very young age, children are given hope and opportunities for success. This includes the right to play, to enjoy what is provided for them by “Nature’s God.”

W.E.B. Du Bois asserts that the “greatest success” of the Freedmen’s Bureau was establishing the free school among Negroes and free elementary education throughout the South. Successful Reconstruction efforts were credited to hard work, the “aid of philanthropists and the eager striving of black men.” 3 But the work of black women educators, such as Laney, is also evidence of success. She did not just establish a school, but one with a classically based college preparatory curriculum for a range of ages. 4 She also let the children find the freedom to play.

- Texts that address the duties of mothers toward cultivating the patriotism of their sons in the early American literature include Patriotism and the Female Sex by Rosemary Keller (Brooklyn: Carlson Publishing, 1994); and Letters of John and Abigail Adams : 1762 to 1826 (New York: Westvaco, 2001). Linda K. Kerber coined the term “republican motherhood” in Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2007) ↩

- Lucy Craft Laney, “General Mortality among Negroes,’ in the Atlanta University Publications, ed. W.E.B. Du Bois (1903; repr. New York: Arno Press, 1968), 18-20. ↩

- “The Freedmen’s Bureau” Atlantic Monthly 1901, http://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/issues/01mar/dubois2.htm ↩

- Laney’s curricula have been discussed in several theses and dissertations, including “’Tell them We’re Rising’: Black intellectuals and Lucy Craft Laney in Post Civil War, Augusta, Georgia by Mary Magdalene Marshall (1998), Lucy Craft Laney– : the mother of the children of the people : educator, reformer, social activist by Gloria T. Williams-Way (1998) and “The burden of the educated colored woman” : Lucy Laney and Haines Institute, 1886-1933” by Britt Edward Cottingham (1995). ↩

Wonderful article! Thank you so much for sharing.