“All of Us Had a Taste”: Outlaw Women and Stephanie St. Clair, Madame Queen of Policy

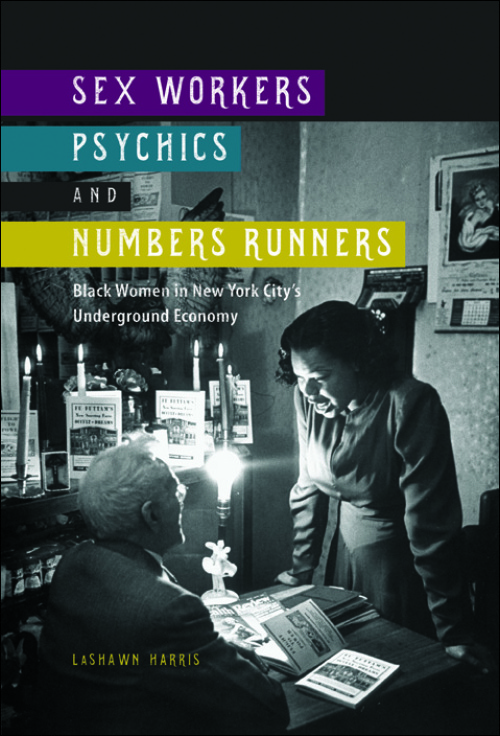

Today is the third day of our roundtable on LaShawn Harris’s new book, Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners: Black Women in New York City’s Underground Economy (University of Illinois Press, 2016). On Monday, blogger Keisha N. Blain introduced the book and its author and yesterday Julie Gallagher provided a general overview of the book. Dr. Harris is an Assistant Professor of History at Michigan State University. Completing her doctoral work at Howard University in 2007, her area of study focuses on twentieth century United States History. Harris has recently published articles in the Journal of African American History, Journal for the Study of Radicalism, and the Journal of Social History. Her first book, Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners, examines the public and private lives of an all-too-often unacknowledged group of African American female working-class laborers in New York City during the first half of the twentieth century.

In today’s post, Shannon King praises Harris’s book for highlighting the stories of “outlaw” black women in Harlem who challenged patriarchy and asserted their personal agency.

Outlaw women are fascinating—not always for their behavior, but because historically women are seen as naturally disruptive and their status is an illegal one from birth if it is not under the rule of men. In much literature a woman’s escape from male rule led to regret, misery, if not complete disaster. In Sula I wanted to explore the consequences of what that escape might be, on not only a conventional black society, but on female friendship. In 1969, in Queens, snatching liberty seemed compelling. Some of us thrived; some of us died. All of us had a taste.1

In the foreword of Sula, Toni Morrison, the Pulitzer Prize and American Book Award recipient, interrogates how black and white reviewers assessed her first novel, The Bluest Eye based on the merit of its “politics.” She writes, “if the novel was good, it was because it was faithful to a certain politics; if it was bad, it was faithless to them.” The judgement was based on whether “Black people are—or are not—like this.” Such, too often, has been the predicament of many African American historians, especially African American women historians. Certainly a key aspect of the ethics and tradition of African American historical work has been to challenge and correct racist and damaging historical interpretations of the past, yet sometimes the stories that might be told “complicates some historians’ efforts to dispel white historical narratives that imagine black women as innately pathological and without sexual restraint” (11). Thus like Morrison, black historians encounter external and internal pressures to produce work that is “faithful to a certain politics.”

In Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners, building on the work of extant scholarship on black women in the urban north, LaShawn Harris transcends these concerns, producing a historical work on black women in Gotham city’s informal economy during the interwar era.2 As Morrison notes, outlaw women aspired to liberate themselves from “under the rule of men.” In that sense, they were not “outlaws” because they were necessarily criminals—but because they sought to escape, challenge, participate in, manipulate, and/or transgress patriarchy and conventions of femininity. As Harris demonstrates, black women snatched liberty through the use of the body—as expressions of love and pleasure and as instruments of violence and repression.3

In Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners, building on the work of extant scholarship on black women in the urban north, LaShawn Harris transcends these concerns, producing a historical work on black women in Gotham city’s informal economy during the interwar era.2 As Morrison notes, outlaw women aspired to liberate themselves from “under the rule of men.” In that sense, they were not “outlaws” because they were necessarily criminals—but because they sought to escape, challenge, participate in, manipulate, and/or transgress patriarchy and conventions of femininity. As Harris demonstrates, black women snatched liberty through the use of the body—as expressions of love and pleasure and as instruments of violence and repression.3

Situating black women’s history beyond the binary of agency/oppression, Harris writes a history where “some of [them] thrived,” and undoubtedly “some of [them] died.” While Harris documents black women’s yearnings “for the intangible rewards and privileges of independent work,” she also tells us about the dangers they faced and the disappointments they endured (35). Harris makes a methodological intervention, writing explicitly of the gendered, race, and class politics that constitute the archive. Despite these tensions within the archive, Harris inquires of it a question that Morrison poses: “what would you be doing or thinking if there was no gaze or hand to stop you?” Morrison answers, “the image of the woman who was both envied and cautioned against came to mind.”

One such woman was Madame Queen of Policy–Stephanie St. Clair. Born on the island of Martinique, St. Clair arrived in New York City knowing only French. St. Clair was a fascinating person; her story was a “rags-to-riches” story, but also a story of love, of violence and betrayal. A successful entrepreneur, yet in an illegal enterprise dominated by men, St. Clair employed black women and men during the Depression. Harris, like other historians, acknowledges the seminal roles that numbers bankers played, both as employers and philanthropist, across the black community. Black bankers, in other words, were doing some of the work that Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “carrot,” otherwise known as the New Deal, could not do.

In Harris’s narration of white gangster Dutch Shultz‘s efforts to commandeer Harlem’s numbers racket, she describes St. Clair’s response as “nationalist.” I wonder if the black community’s collective response to Shultz and others was not only an anti-crime position but also a defense of black autonomy expressed through a form of Black Nationalism or “self-help” economics? As Harris explains, St. Clair joined a chorus of black critics of Shultz and publicly defied him. Fred Moore, the long-time owner and editor of the conservative black weekly, The New York Age, and former alderman, “took issue with white encroachment on Harlem numbers.” For Moore, this was an anti-crime as well as anti-racist stance. He rejected the numbers racket and the police’s targeting of black policy workers, for their “arrests rates were disproportionately higher compared to whites’ numbers laborers” (77).

St. Clair, however, does more than challenge white patriarchy, in the guise of gangster Shultz. She also challenged police violence. In paid editorials in the New York Amsterdam News, St. Clair joined Harlem’s campaign to stop police misconduct in the late 1920s. With firsthand experience with the police, she pointed out the persistence of police harassment and police corruption, including extortion and illegal raids. If we place her community activism, self-determination, economic nationalism, and entrepreneurism in the context of the interwar era, might we conclude that Stephanie St. Clair was a “New Negro”?

Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners, a history of outlaw women tells us much about the conflicting yet co-existing communities within black New York’s imagined black community, as well as raises questions about how we conceptualize black “community,” then and now. How do we understand the ways in which black women endeavored to liberate themselves from the rule of patriarchy in the urban north? How do we make sense of the varieties of “crime” and gender politics in black communities? Undoubtedly, black people rejected crimes of property and against people, particularly black women, but they accepted the numbers racket and extralegal practices by black women who “established home-based unlicensed childcare and boarding facilities for low-income black facilities” (39).

Harris’s work, I think, also urges us to question the logics of capitalism and economic policy. Much like the New Deal, despite President Barack Obama’s stimulus package, the black community continues to suffer. Eric Garner was choked to death for selling “loosies,” single cigarettes in Staten Island, NY in July 2014. And as Harris points out, citing legal scholar, F. Michael Higginbotham, “over the course of the recovery, black women lost more jobs than any other group in the American labor force” (204).

While we need more historical work that operates as a corrective of problematic representations of black people and the past, historians must also continue to write stories of black women and black people generally that “permit them to be fully visible, fully legible, fully human, and thus vulnerable, damaged, and flawed.” Harris’s Sex Workers, Psychics, and Numbers Runners illustrates that those histories have much to teach us, not only about the past but also our present.4

Shannon King is Associate Professor of History at The College of Wooster. He completed a Ph.D. in History at Binghamton University (SUNY). His first book, Whose Harlem Is This, Anyway? argues that Harlemite’s mobilization for community rights raised the black community’s racial consciousness and established Harlem’s political culture. Follow him on Twitter @KingShannon23.

- Toni Morrison, Sula (New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2004). ↩

- Sharon Harley, “Working for Nothing but for a Living: Black Women in the Underground Economy” in Sister Circle: Black Women and Work; Kali N. Gross, Colored Amazons: Crime, Violence, and Black Women in The City of Brotherly Love, 1880-1910; Cheryl Hicks, Talk With You Like a Woman: African American Women, Justice, and Reform in New York, 1890-1935; Cynthia M. Blair, I’ve Got to Make My Livin’: Black Women’s Sex Work in Turn-of-the-Century Chicago. ↩

- My use of “body” builds on historian Stephanie Camp’s discussion of enslaved people having “a least three bodies” in Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women & Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South. I’m suggesting that perhaps emancipation and the migration to the urban south and the north included a fourth body that exploits and employs violence. Historian Jessica Marie Johnson reminded me that Jennifer Morgan, scholar of slavery and gender, made the point about Camp’s “at least three bodies,” which inspired my revisiting the text. For an example of outlaw women and the “fourth body,” see Gross’s Hannah Mary Tabbs. ↩

- Quote from Gross, Hannah Mary Tabbs, 5. Gross’s Hannah Mary Tabbs and Michelle Mitchell’s “Silences Broken, Silences Kept: Gender and Sexuality in African American History” influenced my approach to writing this review of Harris’s important book. ↩

A friend told me yesterday that Raphael Confiant, a Martinican writer wrote a novel about Stephanie St. Clair last year or two years ago. Thought I would pass that info along.