Alain Locke: Father of the Harlem Renaissance

Sometime during the Great Depression, a young working-class Black man acquired a 1925 first-edition copy of The New Negro: An Interpretation by Alain Locke. This book became a prized possession, locked away in a cabinet with other treasures such as E. Franklin Frazier’s The Negro Family in the United States, Charles S. Johnson’s Patterns of Negro Segregation, and James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan. The young book owner had never attended college or even high school, and worked as a domestic servant in the home of a wealthy Jewish family. But his copy of The New Negro, shelved as it was with other texts of the most pre-eminent Black scholars, enabled him to school himself for a self-transformation from Edward Rasmus, one of twelve children in the Jim Crow South, into James Lawrence Curwood, an autonomous middle-class entrepreneur with a Cornell-educated wife and two children, one of whom would graduate from Harvard. The book showed James Curwood how to become a New Negro, living within but not defined by white supremacy, a man at the helm of his own experience.

The New Negro: An Interpretation has been a staple for students of Black aesthetics for decades, having been reprinted in 1968 and in multiple editions since. Gracing the shelves of college bookstores and those of serious scholars of Black history, it signifies a turn in the self-conception of Black Americans from cautious survivors to autonomous citizens. But few have known why it was a gay man named Alain Locke who undertook creating the anthology. Indeed, few know many details at all about Locke–except the facts that he was the second Harvard Black PhD. (after W. E. B. Du Bois).

As it turns out, Locke was a virtuoso of Black self-definition, a master of self-reinvention in his own life and in conceptions of Blackness. In a hefty intellectual biography that evokes David Levering Lewis’s two-volume opus on Locke’s rival Du Bois, Jeffrey Stewart meticulously makes the case for why Locke was the one to introduce the New Negro to the world, and just what his contribution was. The book’s mass, at just under 1,000 pages, is not incidental: Stewart leaves little doubt that Locke was an intellectual giant whose signature achievement grew out of exactly who he was.

And Locke was many things but, most of all, as openly queer as a Black man could be in twentieth-century America. For Stewart, it is reckoning with Locke as a gay man that makes the New Negro moment legible. Locke’s sexuality sent him looking for love with some of the renaissance’s brightest male stars, and when the relationships he wanted were not always attainable he communed with their art instead. He served as a mentor and confidant, and as a middleman between artists and the patronage they needed to meet their bills while pursuing their creative projects. But it was not simply that being gay propelled him toward Black artists. He was able to see the full humanity of Black people because of his freedom from heteronormative thinking. His queerness and “hidden desires” provided him a window into the parts of Black interior life that remained hidden behind the premise that Black people were the sum of their struggles.

On the other hand, his deepest connections to women were as mother figures, and his vision of the New Negro was decidedly masculinist. In the first part of the book, Stewart makes a strong case that Locke’s first and most significant human relationship was with his mother. Mary Hawkins Locke was a quintessential Black Victorian of a prominent Philadelphia family. Having been widowed by her civil servant husband Pliny Locke when her only son was six, she raised the sickly and tiny Alain (born Arthur LeRoy in 1885) by herself, always straining to bridge the gap between her limited finances and the middle-class upbringing she wanted for her son. The boy was a brilliant and charming student who renamed himself while still a child and developed an interest in the study of aesthetics which was really, Stewart posits, “the performance of unfulfilled same sex love.” Locke would remain an attentive son until Mary was buried in 1922, but he did rebel by pursuing art for art’s sake and living the life of a bohemian gay man. The two remained close through Locke’s years at Harvard, his years abroad as a Rhodes Scholar in Europe, and his early career as faculty at Howard. In the famous incident that opens Stewart’s biography, Locke held a wake at their apartment in Northwest Washington. The entering guests were invited to come “take tea with Mother for the last time,” and were astonished to encounter Mary’s well-dressed body propped up on the sofa. The wake would be the subject of gossip and speculation for years afterward, evidence of the depth of his emotional entanglement with Mary. But for Locke, the moment was emancipatory. After that point he reinvented himself for the first time, transforming from a Black Victorian who self-policed his respectability credentials to a New Negro leader who feared neither racism nor homophobia.

It is in the middle section of Stewart’s book that we come to know the architect of the New Negro persona. He was, in Stewart’s word, the “mother” of the movement, with Du Bois the father. Locke’s contribution was nurturing and mentoring. He identified young writers and artists (to whom he was often attracted) and fostered their publication. As his collaborative friendship with Charles Johnson developed, he helped Johnson develop Opportunity magazine into a rival of Du Bois’s The Crisis for publishing the work of the newest group of Black artists. He put together an edition of Survey Graphic as a chronicle of what Locke called the “younger generation” of Black artists. And, as work on that edition was underway, Locke spent several magical days with Langston Hughes in Paris. Locke fell in love with Hughes. But Hughes did not return the feeling, and when Locke discovered that his love would remain unrequited, he poured his emotion into the brilliant introductory essay for the Survey Graphic issue. Knowing Hughes had opened Locke’s eyes to Black people’s capacity for self-determination. That conviction would underlie the expanded book that emerged from the special issue`1 and anchor Locke’s position as the pre-eminent ambassador for New Negroes themselves.

Locke underwent an additional transformation concurrent with his complicated relationship to Charlotte Osgood Mason, patron of Locke, Hughes, and Zora Neale Hurston. After years of living within the manipulative conditions attached to Mason’s philanthropy, Hughes and Hurston broke with her and the middleman of the relationship, Locke. Locke once again was the only and devoted son of a mother figure, and seemed to gather stability from it. He regained his job at Howard after an interval of discord with the institution, and developed a close friendship with the young scholar Ralph Bunche. Through Bunche, Locke engaged with radical economic critiques of capitalism, an outlook he would retain for the rest of his life.

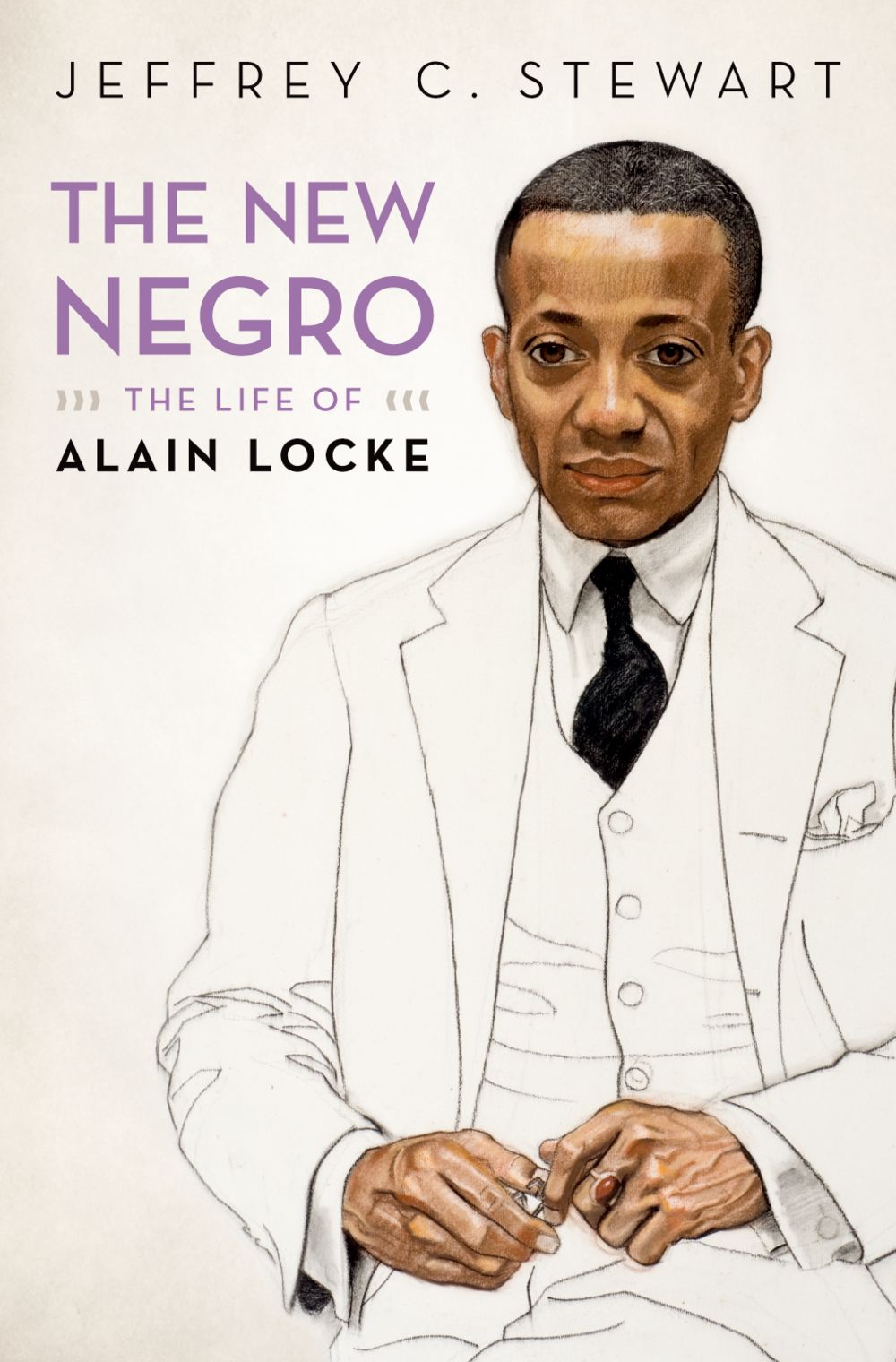

The book itself is a fitting vessel for the life of an aesthete. It is physically beautiful, with the Winold Reiss portrait of Locke on its dustjacket and Reiss’s embellishments from the original New Negro: An Interpretation decorating each chapter’s beginning. Stewart’s biography is no mere birth-to-death catalogue of Locke’s deeds in life; it is comprised of exquisite intellectual detail that Stewart presents as the defining engine of his subject’s development. Stewart does not shy away from male hegemony in Locke’s views, though his framing of Locke’s relationships with some women needs more work. Stewart uses maternalism framework to explain Locke’s relationship with Charlotte Mason as a female-inflected version of Eugene Genovese’s paternalism thesis, itself a now-dated interpretation of enslaved people’s relationship with men who owned them. But the word maternalism has already been claimed by scholars of women social reformers to encompass the gender of power. Maternalism, therefore, doesn’t quite capture the dynamic between Locke and the woman who bankrolled and emotionally tormented him and leaves unexamined Locke’s relationship to the matriarchy thesis that originated with Du Bois and would culminate in the infamous 1965 Moynihan Report, over a decade after Locke’s death.

It is about time that we had a substantive biography of the towering mid-century figure in Black studies, whose relevance reached beyond the academy into the lives of everyday Black people seeking to remake themselves. James Curwood, like Alain Locke, realized his vision imperfectly. Curwood’s own masculinism, not to mention his substance addiction, tore fissures in Curwood’s family, and he took his own life when his Harvard-bound son was just two years old. But his cache of books, and his first edition of The New Negro with it, remains as a testament to his dreams of self-reinvention and Locke’s capacity to engender them.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.