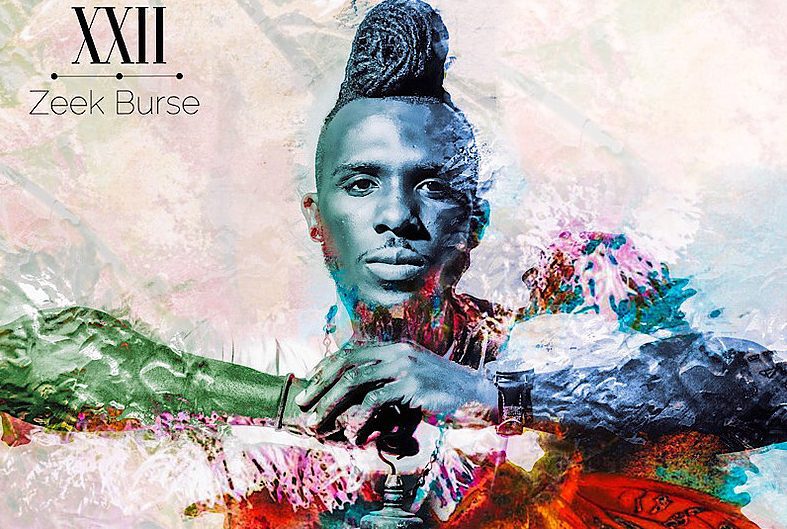

Zeek Burse’s “Broke Man” and the Legacy of the Radical Blues

On his 2017 album XXII, vocal artist Zeek Burse features Paralee Knight on a track Knight co-wrote called “Broke Man.” The song moves first from Burse’s personal affliction because of a lack of resources to a collective identification with the struggles of Black communities in the face of violence, and finally to the resolve “to shine” despite the constraints of an anti-Black social order.

As the song unfolds, it is clear that Burse’s inner-turmoil is fueled by the economic precarity he faces as a musical artist: “I got two suits and seven shows, venue ain’t paying what I want, what I need, and the band has it’s hand out for their fee.” Rather than simply internalizing this as his own shortcoming, Burse draws his economic marginality back to the legacies of slavery and names his desire to fight for the eradication of systems that enforce violence and poverty in black communities: “When I weigh my priorities hungry ambitions gotta feed my needs cause I can’t go back to being a commodity…Wanna do my part and find my voice in this fight/ But vices come easy, education’s priced high/ Broken system yet it wants allegiance from me, but they still killin’ brothas dead in the street.” Finally, against the dismal backdrop of his own economic insecurity and the imagery of Black people murdered in the street, Burse promises “Imma shine a bright light, cause I know what it’s like when you’re trying to get by, But hold your head up high cause we’re gonna survive.”

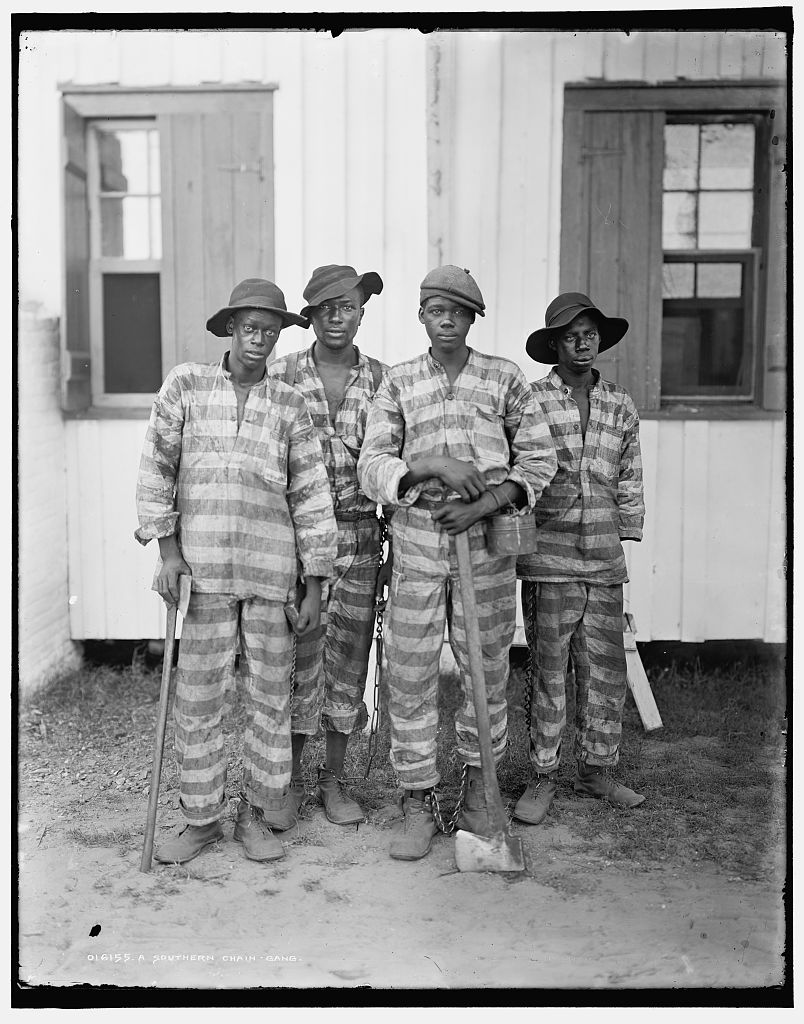

Critically, Burse builds on and makes contemporary a longer musical tradition embedded within the Black Radical Tradition. Even as the classical style of Blues music has declined as a popular form since the 1960s, the Blues epistemology, defined by Clyde Woods as an “introspective and universalist system of social thought and practice,” has continued to flourish in Black culture in the United States and beyond. Specifically, through the lyric and sonic elements of “Broke Man,” Burse taps into a longer cultural history in which Black communities have sought to raise awareness, confront, and interrupt the emergence of social and economic institutions—including chain-gangs, work camps, prisons, and jails—designed to control and profit from socially enforced forms of Black misery, degradation, and geographic sequestering. Burse suggests that the abolitionist tradition of the Blues, whereby its practitioners seek to name and interrupt anti-Black carceral institutions and poverty, extends into contemporary cultural work in R & B, challenging the conditions of ongoing social and physical death to which Black communities are relegated.

The radical impulses against carcerality that are a central aspect of the Blues tradition developed in dialectic with shifting modes of statecraft through carcerality and economic exploitation in the United States from the turn of the twentieth century as Jim Crow consolidated. Born of the battle over the future of resources, and the racial and gendered social and economic order in the aftermath of slavery, the Civil War, and the collapse of Reconstruction, the Blues epistemology aided southern Black communities in articulating visions of their personal and communal wholeness, social integrity, internal complexity, and roving desires beyond the ongoing relations of dominant plantation power. During the first nadir of Black life in the United States, formal public traditions of Black politics that had solidified during Reconstruction were met with white supremacist resurgence and the proliferation of systematized rape and lynching alongside legal forms of social containment.

The crescendo of violence between the 1880s and 1920s banished explicit critiques of the racist social order from public view, forcing them underground and pushing their practitioners to code and distill them into surreptitious and insurgent discourses. In the face of the legal fictions of justice and peace in the aftermath of Reconstruction, the Blues represented a form of what Sarah Haley describes in relation to its Black women practitioners, as “epistemological sabotage” or an art praxis “challenging the very foundations of ideologies justifying [the forms of] carceral control” that underwrote Jim Crow modernity.

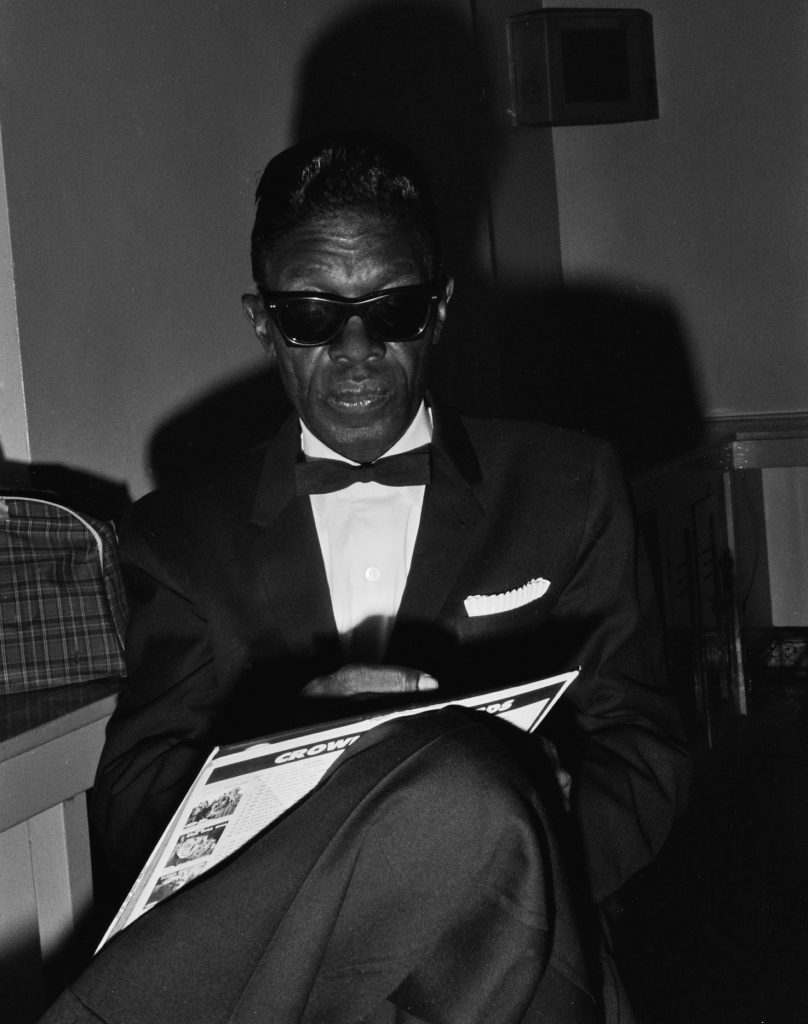

If the Blues emerged with the birth of Jim Crow and the various carceral institutions that undergirded that system, Burse’s work exemplifies the ongoing and robust life of the Blues impulse as we face a social order which is equally nefarious, devastating, and murderous. Earlier Blues songs explicitly excavated the deadly functions of institutions of death like chain gangs and prisons in sundering Black life and posited fugitive modes of resistance that skirted both carceral institutions as well as the normalizing effects of the law. For example, in his 1939 “Broke Man Blues,” James “Kokomo” Arnold narrates his poverty through the metaphor of his “old shack falling down.” Awakened from the terror of a dream that his diminutive house was falling in around him, Arnold woke up with his “head going ‘round and ‘round.” At first, Arnold’s resolution seems at odds with Burse’s embrace of collective solidarity and politics. Arnold embraces becoming “a robber and a cheater” as his way out of the dire conditions of marginality that resign him to a house on the verge of collapse. Burse, on the other hand, announces a desire to connect his work to larger communal political efforts. Yet, both Burse and Arnold are positioned in the realm of the illicit in their ways beyond the acute impact of poverty and carcerality, signaling the deeper interconnections between criminalized forms of fugitive Black life and formally organized social movements.

Arnold embraces the outlaw figure confronting the constraints of legality in eliminating Black poverty by skirting the law and committing crimes of property. In the era of Black Lives Matter–which Burse engages specifically on another track on the album entitled “BLM”–organized non-violent protestors have been marked as prurient social deviants engaged in unlawful assembly and often charged with crimes against property. The territory then of criminalized forms of Black fugitivity is also the realm in which Black social movements operate. Engaging in criminalized forms of individual and collective action is a precondition of disrupting a civil-social order driven by the structural dispossession of Black communities and reinforced by carceral institutions.

Secondly, Burse draws on a sonic tradition of the fugitive, demonstrating the ongoing power of the Blues epistemology in the musical elements as well as the lyrics of contemporary Black popular music. At minute 1:43 of Burse’s “Broke Man,” the chords and tempo shift just as the lyrics describe a kind of scene of flight, in this case from bill collectors. Burse sings to the quickened tempo, “Here we go/ How I’m out of money but there’s still some month left? First notice said sir we didn’t get your check, third notice ask can we meet up next week? Fourth one I bet not catch your ass in the street.” Although Burse appears to be dodging someone to whom he owes money, the music here draws on other historical examples of flight central to the fugitive Blues tradition. Take, for example, Sonny Terry’s harmonica based “Lost John.” On a 1974 recording of the song, Terry narrates the fictive biography of a fugitive named John who flees the police and blood hounds from a chain gang from which he has absconded in Louisiana. Next, Terry’s recording moves to a sonic practice whereby he uses his vocal chords, mouth, and the harmonica to replicate the act of flight in which Lost John is engaged. The shared sonic elements of Burse’s musical and lyrical work in “Broke Man” connect to the history of fugitive Blues which further drives home the continuity of an abolitionist impulse at the heart of the Blues tradition.

Finally, alongside the efforts to reveal the negative effects of poverty and carceral institutions on Black life is embedded the impulse to find a way out despite the overwhelming odds stacked against Black people. Another key component of the abolitionist Blues tradition is a practice of longing, desiring, and hoping for a world outside the carceral geography. Blues performers, including Burse, have often laid out this desire in terms superseding the material world.

For example, in a recording of his “Chain Gang Blues,” Lightnin’ Hopkins sings, “You know I don’t like to go to prison/ You’ve got to work down there too hard.” Here, like Jones and Terry, Hopkins names the drudgery and pain of incarceration as a matter of labor and the social order, calling attention to the role of carceral institutions as engines of statecraft and profiteering. And yet there is a glimmer of hope here that rehearses the opening line of Burse’s song. As Hopkins sings, “Every night you’ve got to pray you going to come out on the help for the lord.” This is similar to the opening lines of Burse’s “Broke Man” in which he sings, “paid my last pennies to the vet on the corner, just hoping it comes back a thousand times.”

Burse’s and Hopkin’s situations are both hopeless in the anti-Black world they share through historical continuity and yet they both also hold onto the Blues impulse by which they indict carceral institutions and seek an out–here through the realm of the spiritually miraculous or fantastic. Burse, like Hopkins, invokes a power beyond the tangible world with the capacity to liberate himself from his constrained position and against a similar backdrop of toil, poverty, and death to the one Hopkins’ generation faced. Although we tend to view this kind of miraculous longing as counter-productive to organized political action, a roving desire for a miraculous intervention is often a precondition of concerted efforts at transformation. Seeking spiritual intervention acknowledges a source of power outside the field of anti-Black social order opening the space of imagination where freedom dreams can flourish. As Burse’s album demonstrates, the critical fugitive and abolitionist impulses of the Blues tradition continue to live on in the work of a conscientious new generation of artists.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Excellent Informative Piece!

Thanks for your engagement Dr. Austin!