Reconsidering Malcolm X and Islam

This is a guest post by Garrett Felber, a scholar of 20th century African American history at the University of Michigan in the American Culture Department. He earned a B.A. in English and American Studies from Kalamazoo College and a M.A. in African American Studies from Columbia University. His dissertation, “Those Who Know Don’t Say: The Nation of Islam and the Politics of Black Nationalism in the Civil Rights Era,” explores the role of black nationalism in the civil rights era by looking at the politics of the Nation of Islam (NOI) in prisons, courtrooms, and on college campuses. His teaching and scholarship focus on postwar social movements, black nationalism, and prison organizing and the carceral state. His scholarship has been published in the Journal of African American History, South African Music Studies, and SOULS. He has also contributed to The Guardian, The Marshall Project, and Viewpoint Magazine. He was senior research adviser on the Malcolm X Project at the Center for Contemporary Black History and is co-author of The Portable Malcolm X Reader with Manning Marable. In 2014, he founded the Black History Study Group at the Columbia River Correctional Institution in Portland, OR.

This is a guest post by Garrett Felber, a scholar of 20th century African American history at the University of Michigan in the American Culture Department. He earned a B.A. in English and American Studies from Kalamazoo College and a M.A. in African American Studies from Columbia University. His dissertation, “Those Who Know Don’t Say: The Nation of Islam and the Politics of Black Nationalism in the Civil Rights Era,” explores the role of black nationalism in the civil rights era by looking at the politics of the Nation of Islam (NOI) in prisons, courtrooms, and on college campuses. His teaching and scholarship focus on postwar social movements, black nationalism, and prison organizing and the carceral state. His scholarship has been published in the Journal of African American History, South African Music Studies, and SOULS. He has also contributed to The Guardian, The Marshall Project, and Viewpoint Magazine. He was senior research adviser on the Malcolm X Project at the Center for Contemporary Black History and is co-author of The Portable Malcolm X Reader with Manning Marable. In 2014, he founded the Black History Study Group at the Columbia River Correctional Institution in Portland, OR.

***

February 21, 2016 marks the 51st anniversary of Malcolm X’s assassination. Malcolm X’s enduring legacy comes not only from his role as a tireless and uncompromising voice for human rights and black self-determination, but also in his ability to act as a prism for a range of themes in 20th century black history. Rather than celebrate his life with familiar tropes about charismatic leadership or his converging views with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., this post allows us to think about Malcolm X in new and generative ways, which speak to our current crisis of Islamophobia. Instead of seeing Malcolm’s trip to Mecca in 1964 as a dramatic about-face in which he was first exposed to orthodox Islamic practices, we might better look toward the rich history of Islam and radical black politics which has been a critical tradition in American history, not something outside it.

Malcolm’s exposure to Islam began in the mid-1940s in Boston and at Norfolk Prison through a community which embraced jazz and Islam as part of a black spiritual and cultural politics. In the summer of 1949, prisoner Malcolm Jarvis wrote to a Muslim in Boston named Abdul Hameed from Norfolk Prison Colony.[1] The epigraph to his letter was a poem by “Red Little” which tied together music and faith: “Music with out the Musician is like life with out Allah – both in desperate need of a home – a body – the completed song and it[s] creator.” Red Little was of course Malcolm X, and Jarvis was the character known as “Shorty” in Malcolm’s Autobiography. Malcolm X was an avid reader and writer of poetry while incarcerated from 1946-1952. His letters home to his family often featured excerpts from Persian lyric poets. But this short letter from Jarvis to Hameed tells us more than Malcolm’s early poetic sensibilities. It reveals a network of Muslims in the postwar period sharing faith and music through prison walls.

From 1949 to 1950, Abdul Hameed visited Jarvis over a dozen times at Norfolk. He brought both men prayer books written in Arabic in 1947 and Jarvis later wrote that “[y]our prayers for Brother Malcolm Little, and I were certainly answered this week.”[2] Although Malcolm names Hameed in his autobiography, he does not elaborate on the foundational role that Shorty, Hameed, and Muslim jazz musicians played in his conversion to Islam. These encounters shaped Malcolm’s intellectual and religious development. They reveal a rich and diverse Muslim community inside American prisons during the 1940s, one which did not disavow jazz as part of a world a petty crime and hustling, but revered it as part of black culture. As Malcolm ended a letter to his brother: “I’m jivin’. I’ll parte [sic] before I become foolish. As Salaam Alaikum.”[3]

Writing to journalist M.S. Handler from the holy city of Mecca in September 1964, Malcolm X denounced Elijah Muhammad and what he called the “narrow-minded confines of the ‘straight-jacket-world’” he had lived in since joining the Nation of Islam in prison in 1948. His letter echoed the Shahada, or profession faith that all Muslims make as one of the five pillars of Islam. “I am a Muslim in the most orthodox sense; my religion is Islam as it is believed in and practiced by the Muslims here in the Holy City of Mecca,” he wrote. Interpretations of Malcolm’s disavowal have varied, ranging from those who believe he had shifted towards a radical humanism and others who see him as maintaining his commitment to black nationalism while broadening to a more orthodox interpretation of Islam. But many at the time chose to focus on his “shifting” ideas about whites. Handler’s ensuing article in the New York Times – “Malcolm Rejects Racist Doctrine” – began by definitively stating that “Malcolm X has renounced the philosophy of black racism.”[4]

When Malcolm wrote Handler, it was a deliberate public relations move. In case Handler was unable to decipher why Malcolm was writing him a ten-page letter with his new religious and political views, he added a final note that “you may always use whatever I wrote you in whatever constructive way you see fit,” asking that the letter also be forwarded to Alex Haley. What is often forgotten in this stark narrative of religious transformation is Malcolm’s first trip to Africa and the Middle East in 1959, which was part of a decade-long effort by both Malcolm and the Nation of Islam to bring the group into global conversations about decolonization, Afro-Asian solidarity, and Islam.

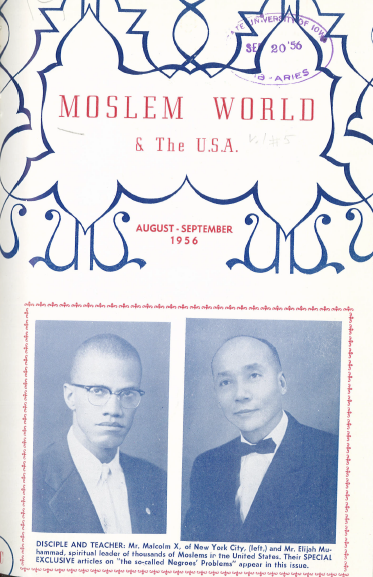

Not coincidentally, these relationships began in the mid-1950s just after the Bandung Conference in Indonesia brought together 29 nations representing over 1.5 billion people around the goals of anticolonialism and nonalignment. That same year, a Pakistani immigrant named Abdul Basit Naeem started a journal in Iowa called Moslem World and the U.S.A., which he hoped would bring together Muslims in the East and West. Although Malcolm is often associated with black newspapers such as the Pittsburgh Courier, Los Angeles Herald-Dispatch, and Amsterdam News, his first editorial – “We Arose From the Dead” – was actually published in Moslem World.

Not coincidentally, these relationships began in the mid-1950s just after the Bandung Conference in Indonesia brought together 29 nations representing over 1.5 billion people around the goals of anticolonialism and nonalignment. That same year, a Pakistani immigrant named Abdul Basit Naeem started a journal in Iowa called Moslem World and the U.S.A., which he hoped would bring together Muslims in the East and West. Although Malcolm is often associated with black newspapers such as the Pittsburgh Courier, Los Angeles Herald-Dispatch, and Amsterdam News, his first editorial – “We Arose From the Dead” – was actually published in Moslem World.

Moslem World was only published between 1955 and 1957, and never reached beyond a modest circulation of 5,500, but it played a crucial role in ushering the NOI into global conversations about decolonization, Islam, and nonalignment. In an anonymous essay which was likely written by a member of the NOI, Islam was not only positioned as the natural religion of the African Diaspora (common to NOI theology), but seen as central tool for African decolonization and the liberation of black Americans. Although the article noted that Islam was the only “world religion or ‘way of life’ that has never been identified with any particular race,” the author also argued that “acceptance of Islam by a black man means that he immediately becomes a full-fledged bona-fide member of the vast Brotherhood of Believers, and no longer remains in a ‘minority group.’” The author echoed 19th-century black intellectuals such as Edward Blyden who saw Islam as the emancipatory religion of Africans. Accompanying a map of Africa which associated the religion with national sovereignty, the article claimed that “if Islam best suits the needs of black Africans, it should best suit the needs of the black men in America as well.”[5]

Naeem continued to write about the Nation of Islam as proof of the spread of Islam in the West. The NOI was featured so prominently that he even felt compelled to publicly deny that the journal was being subsidized by the group. He also stressed the orthodoxy of the NOI, writing that they recited passages from the Qur’an from memory and preformed prayer correctly, even “using authentic Arab accent”[6] He noted that their grocery stores carried no liquor or pork and that the University of Islam was decorated with large flags of Muslim countries in Asia and Africa.[7] Both Naaem and the NOI had begun harnessing the imagery of Third World nonalignment and practices of orthodox Islam before Malcolm’s visit to Africa and the Middle East in 1959.

When Malcolm made his first trip abroad that summer, Naeem was his travel agent. According to the surveillance by the New York Police Department’s Bureau of Special Services and Investigation (BOSSI), Naeem had also become a consultant for the Nation of Islam on “Moslem ritual and etiquette.” Soon after Malcolm’s trip, and Elijah Muhammad’s the following year, “temples” were renamed “mosques,” Arabic instruction increased, and Muhammad’s son was sent to study at Al-Azhar University in Cairo. Malcolm’s dramatic transformation to Sunni Islam in 1964 was as much a necessary strategic repositioning away from Muhammad and the Nation of Islam as it was a radical rethinking of his religious and political views. For both he and the NOI had been part of an international discourse around Pan-Arabism, nonalignment, and orthodox Islam for nearly a decade prior.

Of course, there were fierce debates within African American Muslim communities about the orthodoxy and legitimacy of the Nation of Islam. Jazz trumpeter Talib Dawud of the Ahmadiyya Movement even published a photograph of W.D. Fard with the subtitle: “White Man is God for Cult of Islam.”[8] A Sudanese Muslim student at the University of Pennsylvania, Yahya Hawari (sometimes spelled Hayari), claimed that Elijah Muhammad’s Hajj was illegitimate as it was out of season. But these debates do more than suggest doubts about the Nation of Islam’s religious orthodoxy. They also demonstrate the robust world of Islam in black communities during the Cold War. As politicians now debate the merits of using the term “radical Islam,” it is important to remember the deep history of another type of radical politics and Islam in American history which extended far before Malcolm’s dramatic conversion narrative of 1964, linking people of color around the world in dreams of Third World liberation.

[1] Malcolm Jarvis to Abdul Hameed, July 31, 1949, Malcolm Jarvis prison file (#7465).

[2] Malcolm Jarvis to Abdul Hameed. Also see Malcolm Jarvis with Paul Nichols, The Other Malcolm – ‘Shorty’ Jarvis (Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Co., 1998), 55 and 125.

[3] Malcolm X to Philbert Shah, February 4, 1949, Box 3, Folder 1, Malcolm X Collection, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

[4] Malcolm X to M.S. Handler, September 22, 1964, Box 3, Folder 1, Alex Haley Papers, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and M.S. Handler, “Malcolm Rejects Racist Doctrine,” New York Times, October 4, 1964.

[5] “The Black Man and Islam,” Moslem World and the U.SA. (August/September 1956).

[6] Abdul Basit Naeem, “The south Chicago Moslems,” Moslem World and the U.S.A., (April/May 1956), 23.

[7] Abdul Basit Naeem, “The Rise of Elijah Muhammad,” Moslem World and the U.S.A (June/July 1956), 25.

[8] “White Man Is God For Cult of Islam,” New Crusader, August 15, 1959.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

A high profile individual such as Malcolm? They knew who did it. It’s gonna be interesting what their findings will be. Most will eat it up. But I thoroughly believe, if they do “find” the parties involved, it probably won’t be all of them. I mean c’mon, they’ve diminished this man’s name as if he were Hitler or something. The games they play, smh