Lessons in Law and Order Politics

While many commentators have juxtaposed the bizarre hilarity of the Republican National Convention to the carefully crafted Democratic National Convention, both events shared a robust commitment to the theme of “law and order.” Though their inflections varied significantly, both parties underscored their deep commitment to the ethos that everyday seems to bring news of another killing by police in the country with the world’s largest prison population.

The pre-convention speculation that either affair would resemble the dramatic chaos of the notorious “police riot” 1968 Democratic National Convention never materialized. Yet Clinton and Trump both drew political inspiration from their 1960s forebears. Trump’s speech self-consciously channeled Richard Nixon’s address to the 1968 convention, with its mix of right-wing populism and anti-crime moral panic. Trump regurgitated Nixon’s choice phrase of “law and order.” The term was first introduced into presidential politics four years earlier, when Arizona Republican Barry Goldwater sought the presidency by casting the largely nonviolent civil rights movement as a national menace. Like the parade of D-list celebrities and has-been politicians who spoke at this year’s RNC, Goldwater read the tea leaves of social change and saw American decline.

Goldwater lost the presidency handily to Lyndon Johnson, whose brand of law and order Clinton and the DNC echoed. Months after trouncing Goldwater, whose conservatism he had mocked as a dangerous threat to world existence, Johnson declared a “war on crime.” This initiative funneled tens of millions of dollars to local police to act as both social workers and, well, police. Especially in light of the era’s urban rebellions, the seed money from Johnson’s war on crime would further militarize the police. Johnson wanted to have it both ways, expanding police power while championing the inclusion of African Americans into the polity. In practice this meant an expansion of a small, always precarious black middle class and the debasement of urban working class black (and Latino) communities.

That same desire to have widespread punishment and racial justice too was on display in this year’s DNC. Arguments for Clinton’s expertise came from ex-generals and the former CIA chief, while her husband continued his proclivity to lecture black and Muslim communities about what he still sees as their propensities for violence. In her own speech, Hillary Clinton averred that Black Lives Matter and Blue Lives Matter in the same breath. While avoiding the slogans, Clinton nonetheless equated working for the government as an armed enforcer of the law with simply being black in the United States. Both are dangerous, she said. Both have a right to be fearful. Both need the country’s protection and support.

Even Clinton’s expressed support to “reform our criminal justice system from end to end” has its origins in 1960s law and order. Both Johnson and Nixon commented on the failing of the American criminal justice system. Each one overhauled federal sentencing guidelines and brought federal law enforcement into closer contact with their state and local counterparts. The results included the formation of the Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organization (RICO) Act, which might see Trump convicted for his pseudo-university but which has also been used against low-level drug offenders and radical antiracist and environmental political activists. The 1960s were a turning point in the professionalization of police and the modernization of prisons—all with catastrophic results for the black and brown communities who have been their biggest victims.1

Whether presented as moderate or reactionary, law and order politics is bad for democracy. Both conventions demonstrated the perils of these politics. Law and order is an elastic framework, pliable to either party. It is a potent meme elites use to shore up support in the face of imagined enemies. Like any meme, it cannot be defeated with facts alone. Only a better story, supported by masses of people, can defeat it. Yet part of the danger of law and order politics is its ability to drown out competing narratives of justice. After all, Goldwater went from laughing stock to unacknowledged catalyst of a dramatic realignment of US priorities.

Law and order had its critics. Diverse strands of 1960s-era black activists recognized that law and order bolstered white supremacy. In his famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” Martin Luther King chided white moderates who valued orderly adherence to the law over the pursuit of humanity. Writing after being arrested for protesting Jim Crow, King made an impassioned defense of disobeying unjust laws. More significantly, he said that law and order is a poor paradigm for determining what is right. “I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice,” King declared. White moderates failed to realize that law and order contradicted peace and justice. “I had hoped that the white moderate would understand that law and order exist for the purpose of establishing justice and that when they fail in this purpose they become the dangerously structured dams that block the flow of social progress.”

King drafted his letter in 1963, well before Goldwater sought to ride white opposition to black advancement all the way to the White House. Yet it was Lyndon Johnson who made law and order into the barrier King warned about. Though Johnson signed into law legislation securing voting rights, equal protection, and fair housing, his war on crime would limit the applicability of those challenges to Jim Crow racial order. Once Richard Nixon occupied the presidency, he quickly expanded that war to include a prohibitionist agenda aimed at urban blacks and multiracial leftists. Nixon pledged an “all-out offensive against crime, against narcotics, against permissiveness in this country” while his attorney general, John Mitchell predicted that “this country is going so far to the right you won’t recognize it.”

Not surprisingly, some of the most astute critics of law and order came from its victims in the black freedom struggle. Lynching and police violence led a coterie of black activists to present the “We Charge Genocide” petition to the United Nations in 1951. Throughout the 1960s, the incarceration rate for African Americans increased while it remained stable or dropped for white Americans. By the time the overall incarceration rate began its unprecedented four-decade climb in 1973, prisons had already become a vanguard site of American racism. In his preface to the 1970 reprint of “We Charge Genocide,” Ossie Davis wrote that the expendability of black labor portended the expansion of black genocide. From the outset, law and order politics was built on black bodies.

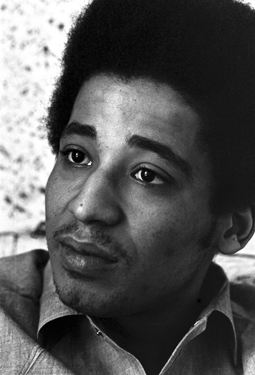

George Jackson was 18 years old when a judge sentenced him to serve between one year and the rest of his life in prison for robbing a gas station of $70 during a joyride with a friend. That was in 1960, and Jackson watched the growing institutionalization of law and order from inside the California prison system that would ultimately take his life. He was killed on August 21, 1971, during a bloody uprising that authorities described as an escape attempt. In a book published weeks after his death, Jackson offered the increasing incarceration rate of African Americans as law and order’s endgame: “The ultimate expression of law isn’t order—it’s prison.” When Jackson wrote that sentence, the United States incarcerated 200,000 people. Today, it locks up more than 2 million.

To Audley Moore, law and order was a racial epithet. No stranger to the racial inequities of the criminal justice system, Moore had campaigned to free the Scottsboro Boys in the 1930s. Law and order was the latest link in the chain. “At first, you were coons, darkies, colored, niggers, Negroes,” Moore told an interviewer in 1972; “then we became crime in the streets.”

Crime in the streets—it is what Trump blames on Muslims and Mexicans and black activists. It is the reason Clinton asks us to do more to protect police, despite all evidence suggesting such wishes are not only unnecessary but counterproductive. The 2016 presidential election may be the first in modern memory to be so routinely described as a “dumpster-fire” of unpopular candidates. Yet for all the high jinks of reality TV and 24-hour-news cycles, the idea of crime in the streets continues to shape the domestic policy agenda of both parties. Regardless of who wins in November, and despite the significant differences between Clinton and Trump, the 2016 election has breathed new life into the country’s already entrenched commitment to law and order politics. It will take more than ridicule to prevent such politics from spreading even further. And it will take more than voting to eradicate law and order as a cornerstone of American politics.

- See, for example, Dan Berger, Captive Nation; Elizabeth Hinton, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime; Naomi Murakawa, The First Civil Right; Robert Perkinson, Texas Tough; and Heather Ann Thompson, Blood in the Water, among others. ↩

What perhaps should also be mentioned is that the 2016 Democratic presidential nominee campaigned for Goldwater in 1964–despite the fact that Goldwater voted against the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Also, there were apparently few speakers on both the 2016 RNC or the 2016 DNC podiums that called for the immediate release in 2016 of U.S. political prisoners like Leonard Peltier, Mumia Abu-Jamal, etc.