Cosmic Literacies and Black Fugitivity

Star-gazing as a practice of fugitivity has a long history for Black Americans. According to folklore, spirituals like “Foller de Drinkin’ Gou’d” covertly educated the enslaved with a vital astronomical literacy — that if one knew how to locate either the Big or Little Dipper constellations, you could easily discover Polaris, the North Star, and follow its steady direction toward freedom. The gourd in the song’s title referenced the hollowed out gourds used by enslaved Africans and African Americans to make spoons and ladles. The white amateur folklorist H.B. Parks reported receiving the story of the song’s possible interpretations in the 1910s from several “old timers” in the Black community in North Carolina, Kentucky, and Texas. Other sources question this provenance, but it is clear that several versions of this spiritual circulated in Black communities during the late nineteenth-early twentieth centuries, and it is well-established how wordplay and other signifying rhetorical games positioned the lyrics of slave songs, often “incomprehensible to white listeners,” as “a device to get round and deceive the whites,” encoded with ambivalent meanings.

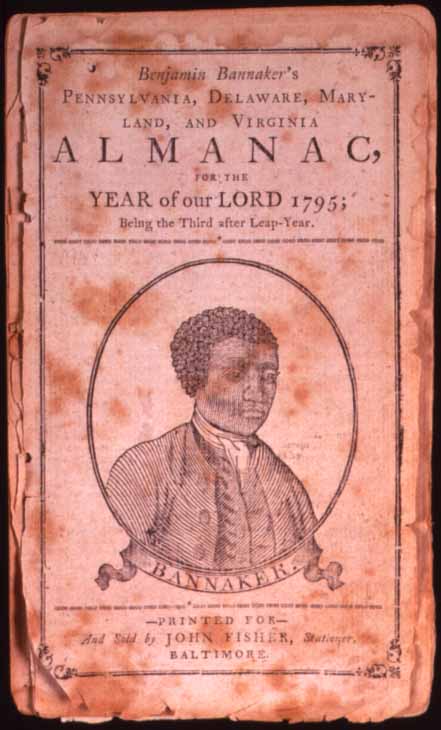

When the autodidact Benjamin Banneker issued his prediction for the solar eclipse of April 14, 1789 that differed from those made by white astronomers, Banneker held his ground and stood in the confidence of his mathematical calculations. He was proven correct and grew to fame as a Black American genius, and was hired as a surveyor of both the land and sky. Banneker’s surveying work eventually led to the publishing of his own almanac in 1792, which contained information about “the Motions of the Sun and Moon, the true Places and Aspects of the Planets….The Lunations, Conjunctions, Eclipses, Judgment of the Weather.” Banneker included antislavery poems and speeches right alongside his celestial and meteorological predictions, and he published this almanac for six years in the mid-Atlantic states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia, ending in 1797. In 1791, shortly before the first edition was published and immediately following his work surveying the site of the new District of Columbia along the Potomac River, Banneker sent a manuscript draft of his almanac to Thomas Jefferson along with a note indicating Banneker’s hope that this example of Black astronomical literacy might help “to eradicate that train of absurd and false ideas and opinions which so generally prevail with respect to” the capacity for Black intellect.

To these examples I add Nat Turner’s 1831 uprising in Southampton, Virginia. While much lore surrounds Turner’s spiritual practices as a mystic Baptist preacher and the veracity of his confessions, the narratives surrounding this human event nonetheless relay much information about the workings of the cosmos based upon Turner’s keen observations of the vast open sky framing the agrarian landscapes of the Old Dominion. Turner’s timeline begins in 1825, when he reported receiving a vision from Spirit that “reveal[ed] to me the knowledge of the elements, the revolution of the planets, the operation of tides, and changes of the seasons.” Turner indicated that this vision caused him to withdraw from the enslaved community as much as possible as he spent time in preparation for what Spirit would have him do. It was sometime later that Turner discovered blood on the corn and in hieroglyphic marks on the trees in the woods, and in 1828 he heard a voice from heaven tell him that God was readying Turner to do His work and fight against the serpent of slavery.

Many students of Black history are probably familiar with the Annular Solar Eclipse of February 12, 1831 whose path passed over south-central Virginia, burning in Turner’s memory the image of a “ring of fire” where the sun normally stood in the sky. As Turner told it, he had been waiting since 1825 for Spirit to give him a sign that would move his plans for Black liberation into their next phase:

And on the appearance of the sign, (the eclipse of the sun last February) I should arise and prepare myself, and slay my enemies with their own weapons. And immediately on the sign appearing in the heavens, the seal was removed from my lips, and I communicated the great work laid out for me to do.

Following this solar eclipse, Turner gathered a group of conspirators to help him carry out Spirit’s ethereal instructions, but he scrapped an initial plan set for July 4th to coincide with Independence Day celebrations, feeling that the time was not ready for such action. Instead, Turner waited for yet one more sign from Spirit, and what happened next in this timeline would require an ensemble effort on the part of the terrestrial and celestial bodies, and presents us with an example of how nonhuman actors come to bear upon those realms of choice and agency so enwrapped within notions of history and historiography.

An article appearing in the Richmond Whig on September 26, 1831 claimed to detail the causes leading up to Nat’s insurrection. The anonymous author told readers that Nat had long claimed to speak directly with Spirit and that his vivid imagination was given to visions. The author continued: “the singular appearance of the sun in August…tempted him to execute his purpose; particularly when its silvery surface was defaced by a black spot, which Nat interpreted into positive proof, that he would succeed….telling [his companions], that as the black spot has passed over the sun, so would the blacks pass over the earth.” Turner himself confessed that he and his conspirators were “still forming new schemes and rejecting them, when the sign appeared again” on August 13, “which determined me not to wait longer.” Many East Coast observers from Maine to Georgia reported seeing this same sign in the heavens. A newspaper from Norfolk, VA detailed how at dawn the sun appeared “a light and lively green” that “changed first to cerulean, then to silver, white, and finally to pale yellow.” It repeated this progression again that evening during sunset, as a Richmond woman confirmed that “about 4 o’clock on looking up at the sun to our amazement, it was as blue as any cloud you ever saw.” The Georgia Courier reported that the sun appeared “shorn of its beams.” Turner interpreted this astonishing atmospheric phenomenon as the final sign he required before bringing his plans to completion. But what exactly was it?

J. Quinn Thornton, an early settler of the Oregon Territory, inadvertently answered this question in his book Oregon and California in 1848. Thornton reported that Mt. St. Helens, a stratovolcano of the Cascade Mountain Range, “was in a state of eruption in the year 1831,” spewing so much smoke and soot into the August sky that “the day was dark, and…candles were necessary.” These effects continued for “several days after the eruption,” when “the fires, out of doors, burned with a bluish flame, as though the atmosphere was filled with sulphur.” Thus, we can gather that the copious amounts of sulfur released by the volcano and pushed eastward by the prevailing winds of the jet stream spread this sulfur throughout the atmosphere, filtering the most intense of the sun’s radiation and giving the orb a blueish tint. In this diminished sunlight, the very surface of the sun became visible to the naked eye and provided many witnesses, including Turner, a direct view of a black sunspot. Eight days later on August 21, Turner’s Rebellion broke out at the Travis Plantation, lasting two days and eventually killing 55-65 whites. The rest, as they say, is history.

Studies in Black ecology locate the plantation as a place from which radical Black politics emerged and where West and Central African folkways found fertile ground in the quarters and upon “the plot” of land worked by the enslaved for their personal sustenance, contributing to the flowering of a distinctly African-American sensibility. But placing Turner’s narrative alongside Benjamin Banneker’s almanac and the folklore surrounding the drinking gourd reveals how complex interactions between both land and sky, heaven and earth, form a genealogy of Black astronomy. Black folk’s observations and perceptions of the nonhuman world, while rarely afforded the legitimacy of empirical science, have nonetheless seeded many political projects of Blackness. Standing upon the terra firma of the plantation, replete with its not-yet-industrialized-or-urbanized landscapes, these radicals turned their eyes heavenward to gaze beyond the veil. They discovered in the stars a knowledge of freedom that constellates together geography, astronomy, volcanology, and meteorology among the many literacies underwriting practices of fugitivity in the antiblack world.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.