The Role of Violence in the Abolitionist Movement

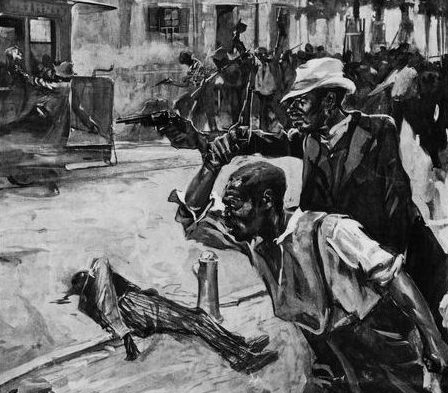

On September 11 1851, George Ford, Nelson Ford, Noah Buley, and Joshua Hammond arrived at William and Eliza Parker’s home in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania near the town of Christiana. The four men were fugitive slaves from Maryland and sought shelter on their journey north. The Parkers, who were Black abolitionists, agreed to help. Shortly thereafter Edward Gorsuch, the white enslaver, and a posse of slave catchers arrived to arrest the fugitive slaves. As the confrontation escalated, Eliza Parker sounded an alarm, alerting the members of the Black Self-Protection Society to protect the runaway slaves. Within minutes, eighty Black men and women and two Quakers arrived armed with guns and pitchforks, ready to defend the fugitives at all costs. Outnumbered, the slave catchers ran off but not until after shots had been fired. Refusing to leave, Gorsuch was ultimately killed at the hands of the men he pursued. Parker later recounted that “the women put an end to him” (p. 54-56).

The successful defense at Christiana was one of the most significant violent altercations over slavery in the 1850s and signifies the volatility of slavery during the turbulent sectional crisis. It also illustrates not only the power of collective Black resistance, but also how Black abolitionist women and men put into practice an ideology they had long embraced: the use of violence in self-defense. Such violence would be required to secure slavery’s ultimate demise. This is the focus of historian Kellie Carter Jackson’s important new book, Force and Freedom: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence.

In Force and Freedom, Carter Jackson sheds new light on the history of abolition and political violence, demonstrating that events like Christiana were chapters in a longer history of Black abolitionists who subscribed to an ideology of force and violence. Rather than marginalized in isolated examples of slave rebellions, in a few writings by abolitionists thinkers, or in individual acts against a slave catcher, the political utility and ideological prominence of force and violence in the struggle against slavery and racism was essential and continuous for Black abolitionists. Racial slavery was inherently violent and African Americans, enslaved and free, understood it would have to be eradicated with violence. Carter Jackson traces how this ideology emerged in the Age of Revolutions and crystalized in the antebellum period, especially after the enactment of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, culminating in a bloody civil war that ultimately brought about the thirteenth amendment abolishing chattel slavery. Carter Jackson’s novel interpretation of political violence recovers an often ignored thread in Black abolitionist thought and enriches a historiography that centers the movement’s radical nature.

In Force and Freedom, Carter Jackson sheds new light on the history of abolition and political violence, demonstrating that events like Christiana were chapters in a longer history of Black abolitionists who subscribed to an ideology of force and violence. Rather than marginalized in isolated examples of slave rebellions, in a few writings by abolitionists thinkers, or in individual acts against a slave catcher, the political utility and ideological prominence of force and violence in the struggle against slavery and racism was essential and continuous for Black abolitionists. Racial slavery was inherently violent and African Americans, enslaved and free, understood it would have to be eradicated with violence. Carter Jackson traces how this ideology emerged in the Age of Revolutions and crystalized in the antebellum period, especially after the enactment of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, culminating in a bloody civil war that ultimately brought about the thirteenth amendment abolishing chattel slavery. Carter Jackson’s novel interpretation of political violence recovers an often ignored thread in Black abolitionist thought and enriches a historiography that centers the movement’s radical nature.

Crucial to Carter Jackson’s ’s argument is the role both the American and Haitian Revolutions played in Black abolitionists’ ideology. “For black abolitionists, the American and Haitian Revolutions involved more than set of enlightened principles: each provided the rationale and means through which to accomplish abolition” (p. 5-6). Throughout the study, Carter Jackson demonstrates how Black abolitionists evoked the legacies of both revolutions and the central role violence played in achieving republican independence.

Importantly, Carter Jackson also situates slave resistance as constitutive to the abolition movement. The slave rebellions of the early nineteenth century carried on the republican tradition of using violence to obtain freedom. Including slave rebellions in the history of the abolition movement reveals the limitations of older strands in the historiography that privileged the antebellum era over the early republic. In effect, it reorients the movement’s chronology. In turn, this framing contextualizes David Walker’s famous Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World (1829) defending slave rebellions and the use of violence in self-defense. Thus, by the 1820s abolitionists’ calls for political violence yielded some support.

The evolution of abolition in the early 1830s and the advent of William Lloyd Garrison popularized the tactics of moral suasion and shifted the movement away from political violence. Interestingly, the advent of Garrisonian moral suasion, typically seen as igniting a new phase in abolitionism, instead represents a disruption in the support for political violence. A pacifist, Garrison believed in appealing to white Americans’ sensibilities to see slavery as a sin and demanded immediate abolition. While Garrison opposed violence, he did support the right of enslaved people to rebel. More could be said about Garrisonian abolition in this section and particularly the politics of agitation. Moral suasion was most successful in expanding the movement’s constituency, mainly by converting northern white evangelicals to the cause. But over time, it was clear that moral suasion was woefully inadequate in bringing about emancipation and Black rights. Carter Jackson shows how Black abolitionists were keenly aware of these dynamics. African Americans supported the tactics of moral suasion when it was useful and for fostering interracial ties in the movement. But they also believed in the use of force when the situation warranted it. Carter Jackson shows how Black abolitionists like Joseph C. Holly had an eclectic outlook on abolitionist tactics, supporting moral suasion alongside political abolition and violence. By the 1840s, individuals like Henry Highland Garnet saw the proverbial writing on the wall: moral suasion had run its course. Garnet’s famous speech “Address to the Slaves” (1843) marked a turning point, as he, and later Frederick Douglass, joined Maria Stewart, David Ruggles, and Phillip Bell, who all embraced the use of force in the 1830s, in calls for political violence.

The heart of Force and Freedom focuses on the tumultuous decade of the 1850s, when employing political violence in self-defense and as a means of radical reform became a lived reality for African Americans, free and enslaved. Carter Jackson details how the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act invigorated the movement and brought to the fore the widespread necessity of political violence as an abolitionist tool. Black Americans and their white allies formed vigilance committees and militias for collective defense against slave catchers. The author specifically emphasizes the strength of collective resistance at the grassroots level as she details how towns like Christiana, and cities across the North, became flashpoints over the Fugitive Slave Act. In essence, they exemplified the effective use of political violence. By the early 1850s “the days of nonresistance were over;” and abolitionist tactics evolved from “prayers and petitions to politics and pistols” (p. 77, 105).

Most significantly, Carter Jackson illustrates how Black women played a prominent role in championing political violence. She illustrates how African American women like Eliza Parker and countless other women were just as likely as men to use force. For example, upon being pursued by slave catchers, the fugitive slaves Mary Grigby and Emily Foster pulled guns on the pursuers: “With a double-barreled pistol in one hand and a long dirk knife in the other, the woman shouted back, ‘Shoot! Shoot!! Shoot!!!’’ In one of the strongest chapters in Force and Freedom documenting the Black abolitionist impact on the Raid at Harper’s Ferry, the author shows how Black women were instrumental in planning the raid and enacting it. John Brown deeply admired Harriet Tubman for her leadership in the Underground Railroad and drew inspiration from her unflinching use of a pistol. Without Black women, the raid might not have occurred. Mary Ellen Pleasant, a Black entrepreneur, donated some $30,000 to Brown’s efforts in organizing the raid. Anna Murray Douglass also aided Brown and welcomed him into her home as the raid was planned. Black women like France Ellen Watkins Harper sent money to aid Brown’s wife after he was executed. Indeed, Carter Jackson irrefutably demonstrates that accounts of John Brown as an individual white savior are completely ahistorical when we understand how Black abolitionists aided him and influenced his decision to use political violence.

Force and Freedom is a tour de force study that centers Black resistance and the significance of political violence in abolition. One critique that has been raised elsewhere is how African American Christianity, and I would add African religions, influenced Black abolitionist support for political violence. The impact of religion is especially significant for Garnet and abolitionists who were ministers as well as other practitioners of Black Liberation theology. A question for future research is whether there was a generational divide among abolitionists who supported violence and those who did not. These observations, however, do not detract from Carter Jackson’s significant contribution to abolition studies.

As Carter Jackson writes, Black Americans won freedom, it was not given; and it was violence that brought about the revolutionary outcome of the Civil War. Abolitionists did not fail; which is evidenced by the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth amendments and the revolutionary period of interracial democracy during Reconstruction. However, the enduring force of white supremacy would overturn such gains. A lesson from Force and Freedom for today is an abolitionist one: in order for there not to be violent resistance to a violent system, the violent system must be eradicated. It is this work that needs to be done, and white Americans must learn such lessons if there is to be an interracial democracy in the United States.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.