The Legal Mind of Constance Baker Motley

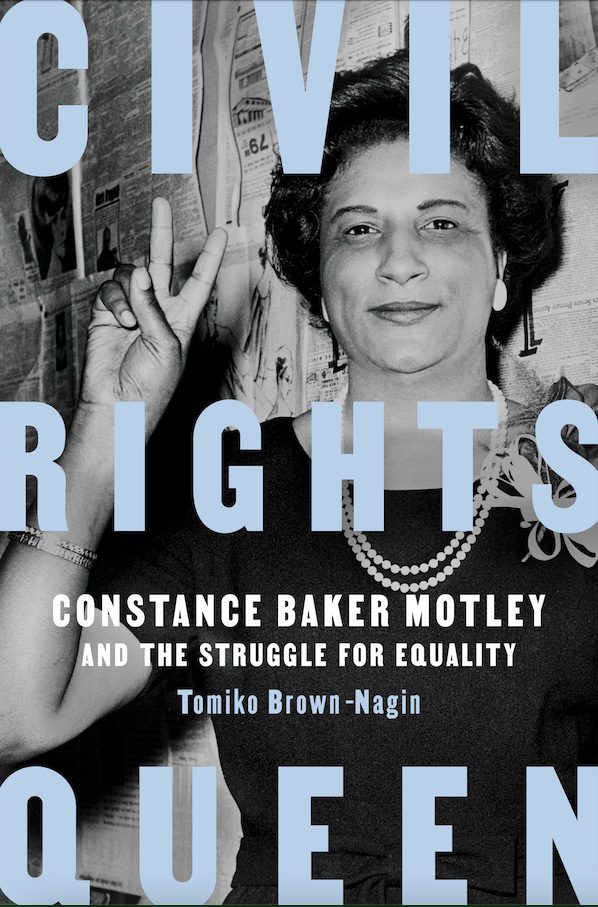

This post is part of our forum on Black Women and the Brown v. Board of Education decision. The following is an excerpt from CIVIL RIGHTS QUEEN: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality by Tomiko Brown-Nagin. Reprinted by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2022 by Tomiko Brown-Nagin.

In 1953, after Earl Warren, the former governor of California, joined the [Supreme] Court as chief justice, the Court asked the lawyers to reargue questions related to congressional intent. The Inc. Fund’s team, aided by numerous scholars and outside lawyers, embarked on new rounds of debate, research, writing, and oral argument before the Supreme Court. In September 1953, Thurgood Marshall convened the entire “formidable” group of the “most brilliant” people in their fields, one hundred strong, in a three-day conference to present and test arguments. Bob Carter called the conference an “exhilarating intellectual experience.” The feverish preparation culminated in a December 1953 oral argument before the U.S. Supreme Court. [Constance] Motley looked on with pride as her colleagues argued, in turn, that the “separate but equal” principle should be overturned. The Court must reject segregation, Marshall argued, because the only thing that explained it was whites’ “determination that the people who were formerly in slavery . . . shall be kept as near that state as possible.” That rationale offended the Constitution.

In the spring of the following year, the Court issued a unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education. Relying in part on social science data, the Court held that state-sanctioned school segregation violated the Fourteenth Amendment. The justices rooted their unanimous decision in a recognition of the vital role of education to success in American life. “Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments,” the Court wrote. “It is the very foundation of good citizenship.” States could not lawfully provide education of different calibers to students on account of race, the decision explained. “We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” The lawyers had achieved an astounding legal victory in a case that many would call the most important constitutional case of the twentieth century, and perhaps in U.S. history.

The LDF attorneys and their allies celebrated into the wee hours. Motley recalled that she shared with her colleagues the “high” gained from “making history.” Like them, she basked in both the professional stature that Brown conferred and the knowledge that the “original sin” of American law had been removed. Black Americans had attained a new freedom. Future generations, including [her son] Joel III, would reap the benefits of the work, an overjoyed Motley explained to her infant as he sat in his high chair that evening.

Reactions to the decision by news commentators and ordinary people alike ensured the prominence of the Inc. Fund lawyers who had successfully argued the cases. Commentators called Thurgood Marshall a “brilliant” legal tactician and “defender of American democracy.” The charming, earthy lawyer had made a powerful impression on the world as the standard-bearer for the argument against segregation. Marshall’s entire team received praise. The Inc. Fund attorneys became “legal giants.”

Constance Baker Motley had played an integral role on the legal team responsible for the landmark victory. As the five school cases wound through the federal courts and on up to the Supreme Court, she conducted invaluable legal research and helped write the legal pleadings and briefs needed to move the cases forward. In 1950, after the Court had paved the way for Brown by ordering the admission of a Black man to the flagship University of Texas School of Law who had been shunted off to a purportedly “separate but equal” Black law school (Sweatt v. Painter), Motley had drafted a blueprint for the coming frontal assault on segregation. She wrote and distributed to NAACP-affiliated counsel a model complaint—the critically important document that instigates a lawsuit and, if well done, survives defendants’ efforts to get the case thrown out of court. The complaint Motley drafted set forth the facts and the law that explained why segregation violated the Constitution and why the Inc. Fund’s clients were entitled to a remedy (in this case, a desegregated school). Thus, when lawyers in Kansas and in the other Brown cases filed claims attacking school segregation, they were building on Motley’s intellectual handiwork.

Following the Supreme Court’s request for re-argument in the five Brown cases in 1953, Marshall and [Robert L.] Carter assigned Motley to another vital task. They asked her to review legal cases relating to the scope of congressional and judicial power to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment— a decisive issue that the justices touched upon during oral argument in the Brown cases. Could the framers have authorized desegregation of the schools, something then unheard of, through the open-ended language of the Fourteenth Amendment? The Inc. Fund hoped to convince the justices that even if Congress had not intended in the Fourteenth Amendment to end school segregation, the Constitution authorized the Court to interpret the amendment in that manner. Motley’s legal research provided support for the Inc. Fund’s contention. She also proofread the briefs—“nightmare” work that she, “the girl in the office,” “endured,” she recalled. In view of her many contributions to the Brown litigation, the organization’s briefs to the U.S. Supreme Court credited Constance Baker Motley as “of counsel.” In a long list of over a dozen attorneys whose names appeared on the briefs, her name stood out: she was the only woman in the illustrious group.1

Nevertheless, Motley played a circumscribed, if critically important, role on the legal team. Marshall had determined, through “delicate negotiations,” “who would argue which case in the Supreme Court.” The assignments brought glory and enhanced the chosen lawyers’ reputations. Numerous press materials highlighted the lawyers’ responsibilities in the cases. The men were the stars of the team. Photographed on the steps of the U.S. Supreme Court after oral argument, they had their pictures plastered across newspapers nationwide. Thurgood Marshall had shouldered the heaviest burdens of the historic cases, and, after winning, enjoyed the utmost adulation. For his leadership in the campaign against segregation that culminated in Brown, he became a household name—and “Mr. Civil Rights.”2

Motley, by contrast, was part of Brown’s supporting cast—a vital team member who worked behind the scenes. Instead of participating in Supreme Court oral arguments of the cases, she observed them from the audience. The trial lawyer enjoyed a level of professional distinction supporting lawyers could not quite match. The exalted reputation of litigators rested on an attorney’s ability to think “on his feet.” The courtroom lawyer had to respond to questions from the bench and, during trial, pose pertinent questions to witnesses—all under the pressure of public scrutiny. Without the opportunity to demonstrate her prowess in the courtroom, Motley did not yet command the same level of attention and adulation as her colleagues.3

The slower track that Motley was on, likely related to her gender, was especially clear in comparison with the career path of Jack Greenberg. The Inc. Fund considered Greenberg Motley’s closest peer in terms of rank and seniority. In reality, however, Motley had begun working at the Inc. well before Greenberg. He had joined LDF the same year, 1949, that Motley had won promotion to assistant counsel. Marshall had hired Greenberg, a World War II veteran, on the recommendation of Walter Gellhorn, an esteemed Columbia Law professor, who touted the young man’s “brilliance.” With these auspicious beginnings at LDF, Greenberg quickly earned Marshall’s confidence.

By 1954, Greenberg and Motley held the same rank, but Greenberg had gained more—and more significant—courtroom experience. In 1950 he was overjoyed when Marshall assigned him to handle his first big case: taking on segregation in the undergraduate program at the University of Delaware. He also aided Marshall in representing a defendant in the infamous Groveland case—the “worst case of injustice and whitewashing” Marshall had ever seen, in which four Black men had been wrongly accused of raping a white woman in 1949. A sheriff’s posse murdered one of the men, and an all-white jury sentenced two of the remaining men to death, and sentenced the third, merely sixteen years old, to life in prison. In 1951 Marshall and Greenberg successfully appealed the conviction to the U.S. Supreme Court. Although an all-white jury again convicted the defendant after retrial, the lawyers’ work on the Groveland case enhanced their reputations and deepened their relationship. (Seventy years later, the governor of Florida pardoned the four accused men, calling the case against them a “miscarriage of justice.”)

During the same period, while Motley had worked on significant cases, they were fewer in number and of a lower profile. The lawyers’ disparate experiences culminated in 1954, when Greenberg argued one of the Brown cases in the U.S. Supreme Court, while Motley contributed to the research and writing of the Inc. Fund’s legal complaint and briefs—and did “drudge” work.

The pace and arc of Motley’s career are better understood in light of a life-changing event. At the same time as she was seeking to advance professionally and support the Inc. Fund’s bid to overthrow segregation, she became a mother. Joel Motley III was born on May 13, 1952, in New York City. At thirty years of age, Constance Baker Motley was much older than most other first-time mothers of her day. She had postponed childbirth to attend college and law school during her twenties, a decade of life when most women were marrying and starting a family.4

Motley worked until her baby was due to arrive and took a three-month leave of absence after giving birth. She returned to work full-time in mid-August, right in the middle of frenzied preparations for Brown v. Board of Education. A deadline hovered: the new mother helped to draft and revise briefs in the case, due to the Court in September, the month after she returned to the office…

Read the rest of the story and more about Constance Baker Motley in Tomiko Brown-Nagin’s Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality.

- See NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., Monthly Report, June 15—September, 15, 1953, p. 2; Brief for Appellants in Nos. 1, 2 and 3 and for Respondents in No. 5 on Further Re-argument, Brown v. Board of Education (October 1954). ↩

- See NAACP LDF Press Release, “Filing of Brief Ends 22 Hectic Weeks for N.A.A.C.P. Lawyers,” November 16, 1953. ↩

- See NAACP LDF Press Release, “NAACP Attorneys Tell Justices That Dixie Education Pattern Violates 14th Amendment,” December 12, 1952. ↩

- See Constance Baker Motley to Thurgood Marshall, n.d., NAACP Papers; author interview with Joel Motley III. ↩