The History and Failure of Prison in Washington

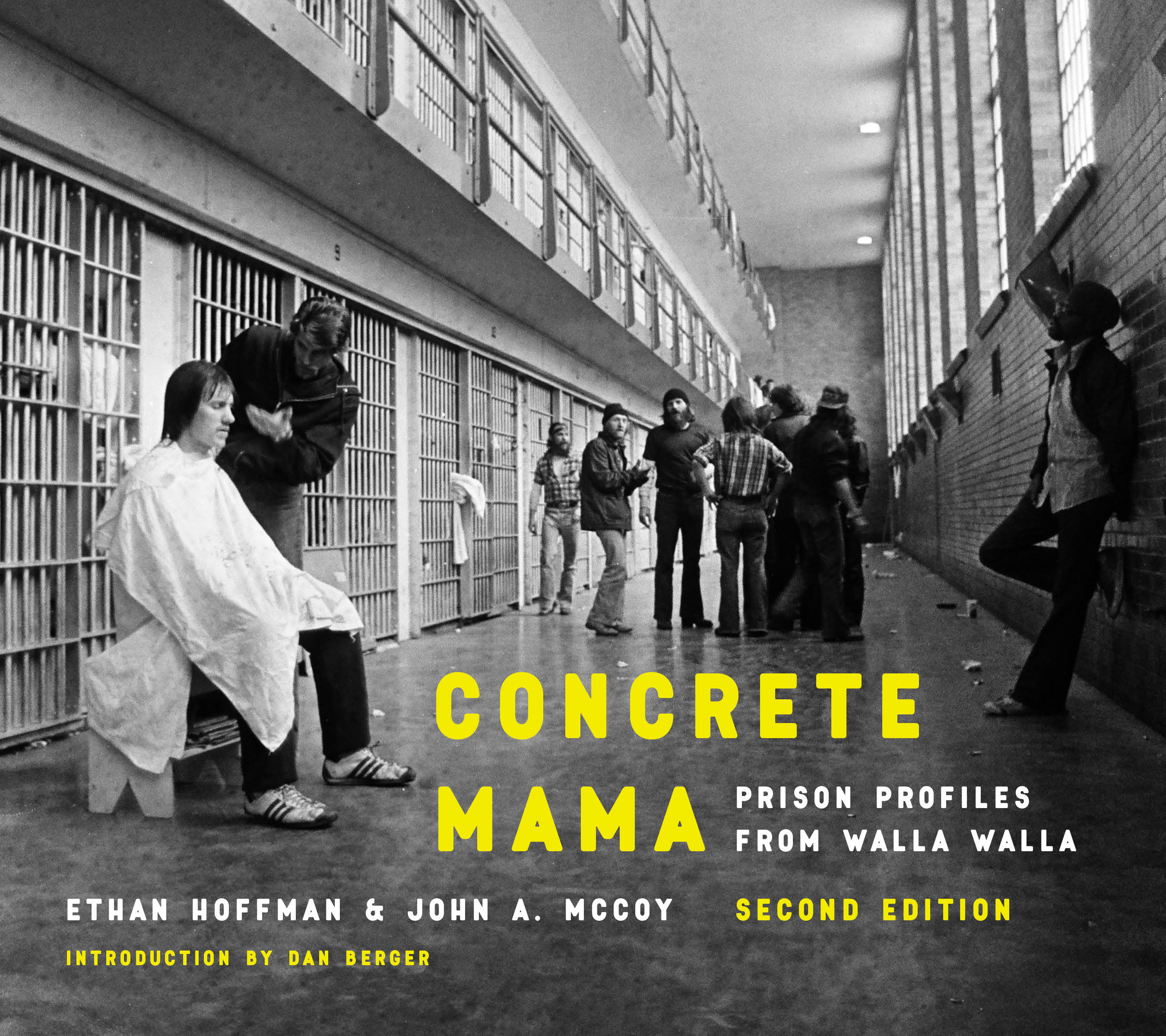

The following essay is excerpted from my introduction to the second edition of Concrete Mama: Prison Profiles from Walla Walla, the award-winning 1981 photo essay by journalists John McCoy and Ethan Hoffman that captured the prison’s transition from an interesting but unsupported experiment in prisoner governance to a maximum-security lockdown facility. This excerpt was reprinted with permission from the University of Washington Press, which has recently republished the book.

***

John McCoy and Ethan Hoffman were young journalists when they immersed themselves in the world of the Washington State Penitentiary in the late 1970s. They entered a decaying prison in southeastern Washington that was moving between two grand experiments: one an ill-fated half-attempt at prisoner-shared governance of the institution, the other a still-unfolding cruelty of warehousing large masses of people. In words and pictures, their chronicle lays bare the fault lines of punishment as the United States toggled from bungled reform to an unprecedented expansion of human caging.

When the pair entered prison for a four-month stretch in 1978, the Walla Walla penitentiary was in a moment of transition. In fact, the entire landscape of American prisons was undergoing a similar move. The previous decade had been a tumultuous period in an institution marked by its own brand of mayhem. What we now call “mass incarceration” began with two simultaneous developments: an expansion of criminalization and a crackdown on prisoner self-organization. Whereas the first trend sent more people to prison for longer periods of time—and ultimately necessitated the biggest rush of prison building in world history—the second aimed to remove nearly any vestige of collective action inside. The result is 2.2 million people incarcerated, idle and incapacitated, in austere institutions nationwide.

These twinned moves occurred in response to a dramatic, at times chaotic series of events—events led by guards as well as prisoners. Both the keepers and the kept revolted against the prevailing order of punishment, each pursuing different agendas. Prison itself, as a concept and an institution, suffered a crisis of legitimacy in these years. This crisis threw the future of the institution in doubt, as what many assumed to be the rationale for prison—rehabilitation—was challenged from both Left and Right. From the Left, rehabilitation was a facade: the endemic racism, censorship, and basic lack of bodily integrity, religious freedom, adequate medical care, and other civil and human rights showed as much. To the Right, these realities suggested the failure of trying anything but incapacitation: lock ’em up and throw away the key.

A Novel Experiment

A year before the Attica rebellion showed American prisons to be places where brutal racism anchored abusive standards of living, a liberal administrator in Washington State announced what LIFE magazine dubbed “a new way to run the Big House.” William Conte wanted to move state prisons away from the pure custody approach to a more European model, where prisoners serve shorter sentences in smaller prisons with more access to people and projects on the outside, more programming and involvement on the inside. The centerpiece of Conte’s reform was the formation of the Resident Government Council (RGC) to establish prisoner self-governance. Conte also eased censorship restrictions, extended telephone and visiting privileges, and allowed prisoners to wear civilian clothes.

At least that was the plan. The warden and many guards resisted these changes. After a series of prisoners were disciplined or placed in isolation for growing long hair, prisoners organized a strike under the motto “If you care, grow hair.” The seemingly frivolous issue captured the spirit of the times. Beginning on December 23, 1970, the 1,345 people incarcerated at Walla Walla remained in their cells for ten days in protest. Following the strike, a group of Black and white prisoners vocally opposed the racist attacks that typically governed the prison. They formed a Race Relations Committee to implement their plan. Fighting prison racism gave incarcerated people the practical experience to govern their affairs. The Race Relations Committee led to the formation of the RGC, which held its first election in April 1971. The RGC, an elected body of eleven prisoner representatives, would ostensibly share power with the prison administration in running the institution. Despite a broad leeway that American prisoners have rarely enjoyed, however, the RCG was never the parallel form of governance that some had hoped—or feared—it would be.

By 1973, the RGC had been defanged. A member of the RGC charged that the warden was using “‘divide and conquer’ methods, which aimed at ‘breeding distrust and contempt’ between members of the RGC and their constituents.” Warden Rhay disbanded the RGC in 1974 and turned to the Washington State Prison Motorcycle Association (WSPMA)—a confederation of imprisoned members of different outlaw biker gangs—to enforce prison discipline. A remnant of the council persisted, serving as a bludgeon that powerful men wielded for their own benefit in the stratified world of the penitentiary.

Severe as they may be, the hierarchies of prison are not exceptional but, rather, more exaggerated forms of the divisions that exist on the outside. Writing from the Washington Corrections Center for Women at Purdy, Therese Coupez, who was incarcerated for her participation in the revolutionary underground George Jackson Brigade, noted the dangerous error in “viewing prisons and prisoners as somehow a different, exclusive, unrelated issue” from the rest of society. Instead, prison magnifies the tensions that run through the social world. The prison operates through classification: it officially separates people by sex and criminal offense; it divides them further, if unofficially, by race, religion, geography, politics, and sexual orientation or gender presentation. Prison racism flows from the racism of society as a whole. Nowhere is the old Marxist saw—that racism divides working-class people from fighting the ruling elite—more true than in prison, where almost every single person comes from a poor or working-class background.

Racism structures the space of prison. At the time Concrete Mama was written—more than a decade after civil rights legislation was said to have ended racial segregation nationally—racism determined which table a prisoner could sit at in the mess hall, which shower he could use, which club she could join. Washington State prisons remained segregated this way into the 1990s. Walla Walla did not integrate its cafeteria until the twenty-first century.

Beyond the Walls

“Prison is full of a lot of sadness,” John McCoy told my students. “It’s also full of humor, occasional joy, irony. But it was the sadness that got to me at times.“ As McCoy notes in his introduction to this book, even the four months he and Hoffman spent at the penitentiary affected them: they were more paranoid, defensive, and irritable than they had been before. Their time in prison was brief, voluntary, and productive; nonetheless, they too had to heal from the experience.

Prisons destroy people. There is no other way to say it. They destroy people who do the imprisoning and those who are imprisoned. Prison both comes from and perpetuates social, political, and economic ills. As the poet Anatole France said, “The law, in its majestic equality, forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal their bread.” People can do terrible things to each other. Yet as long as prison remains the go-to solution, society will fail to take meaningful steps toward addressing harm or the conditions that cause people to act harmfully.

People do change, often more despite prisons than because of them. In reflecting on his own transformation from “the meanest man in Washington State’s toughest prison” to a “good father, a respectful neighbor, an excellent employee, and a nice man who shops at local stores,” Al Gilcrist did not credit his time at Walla Walla. Instead, Gilcrist, who was released in 2005, said he learned from those opposing injustice: “Ultimately, it was the civil rights attorneys, not the guards with riot batons, that convinced me that there was a better way to live. . . . Gradually, I began to change because I had positive models to emulate.” A similar message can be found in the books, plays, poems, posters, videos, campaigns, strikes, symposiums, and assorted other projects now being created by and about incarcerated people.

What Concrete Mama shows now, decades after its first publication, is not the failure of prison reform but the failure of prison. It is not the only book to illustrate that fact, but the book illustrates it in a particularly vivid way—at least for those willing to extend empathy to the book’s subjects. We see how prison destroys people. And we see how some people refuse to be destroyed; the book illustrates that too. The remarkable portraits of perseverance and vulnerability reveal that people can transcend the worst thing they ever did and the worst thing ever done to them. Revisiting this book now offers the opportunity to look at both sides of the equation: Prisons destroy people. And yet some people refuse to be destroyed.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.