Notes from the Library: Gerrit Smith and the Problems of Politics

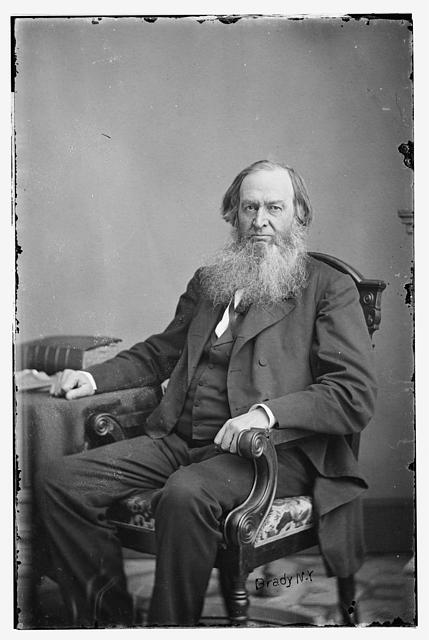

Gerrit Smith wanted to solve the problems of the antebellum United States. He hated slavery, so he bankrolled John Brown. He believed in agrarianism, so he offered black families land grants in upstate New York. And though he had qualms about the electoral process, he overcame them and brought his uncompromising outlook to Congress for one term. “The great political evil of the world,” Smith declared in 1846, “is not, that so few vote—but that they, who do vote, vote so ignorantly, so selfishly, so tyrannically.” Smith continued, “how painful to the heart of enlightened benevolence is an American election! . . . a perverting of Civil Government from its merciful work of caring for the needy and the oppressed!” He published those comments in a pamphlet that was his response to seven black men who had sought his support for equal suffrage in New York State. Activists looked hopefully toward a state constitutional convention planned for the Summer of 1846. Twenty-five years earlier, the state had adopted a constitution that effectively disfranchised African Americans by imposing a $250 property requirement for black voters. The new gathering might correct what some lawmakers called an “unjust discrimination;” it was an opportunity to get black suffrage back on the table. Activists asked Gerrit Smith to support convention delegates who favored an equal suffrage amendment. Smith, though he called himself a “friend and brother,” refused to promote black voting rights. Smith’s pamphlet reply tells us about his problems with politics as well as the ways antislavery challenged and restricted antebellum black protest.

This Fall, I am a fellow at the Library Company of Philadelphia, which holds extensive collections of early American printed materials, including more than 13,000 items related to African American history. Among them is that 1846 pamphlet addressed to William Rich, James Henderson, Francis Lippins, John Wendall, Charles Morton, Richard Thompson, and William Topp. Those seven black men from Albany sent Gerrit Smith a five-page letter in which they argued that black suffrage must be “the point at issue” for the convention and that Smith should support any delegates, “Whigs or Democrats,” who pledged to support black enfranchisement.

In reply, Smith chided his correspondents, sketching for them a proper constitutional convention. Delegates should not seek “this one good thing, or that one good thing,” but should instead try to “obtain for the people of the State a Civil Government,” a set of structures that would protect “the needy and the oppressed.” The convention could be broadly transformative, expanding participation in government and remaining attuned to the projects of ensuring freedom and equality. In theory, that sweeping transformation would provide for black suffrage, but Smith’s vision was also narrow, filtered through his investment in the Liberty Party, which had met moderate success in the Election of 1844 and revealed the possibilities of political antislavery. He was uninterested in supporting “Whigs or Democrats,” or any other delegates he felt had not exhibited substantial “antislavery character.” Despite any pledges they might make, delegates who had supported slaveholders could not be trusted to vote for black suffrage. “You would trust no man with your key, of whom you required a pledge not to steal your money.” Smith remained uncompromising, refusing to become “a traitor to the slave” in search of black enfranchisement.

The constitutional convention met in June, and through a series of debates in the summer and fall, delegates agreed to offer voters a separate referendum ballot on the issue of “equal suffrage to colored persons.” On November 3, 72% of New Yorkers voted against equal suffrage.

The referendum did not fail because Gerrit Smith disagreed with seven black men from Albany. Their dispute did not prevent delegates from crafting a constitutional amendment on black suffrage. But the world of pro- and antislavery politics in which Smith worked stood in the way of other forms of black activism. Black New Yorkers who met the property requirement could vote on the referendum, and many likely favored black enfranchisement in hopes that it would disrupt a pattern of increasing legal restrictions tied to race. Black New Yorkers, though, constituted a small minority of the electorate. The democratic process demanded that black activists seek support from white abolitionists, their most likely allies, in their push for a new suffrage law. But Gerrit Smith’s approach to activism was not democratic. “Our business, as abolitionists, is to maintain and apply our abolition principles,” he wrote, “and not to barter them away for universal suffrage.” Smith admitted that suffrage was important, but he felt obligated to point out to the black activists “the infinitely greater importance of adhering to our principles.”

Gerrit Smith “desire[d] . . . not that every man vote, but that every man cast his vote in the right spirit and for the right ends.” Smith was convinced that he knew that spirit and those ends. He was a problem solver. He assumed the authority to instruct people how not to vote selfishly, ignorantly, or tyrannically. And he made an argument about which black people constituted the truly “needy and oppressed.” Black activists did not abandon the enslaved when they looked to Whigs or even Democrats for support. They sought to seize the unique opportunity of a constitutional convention to shape the content of their freedom, the same freedom into which they anticipated the enslaved would enter. Gerrit Smith’s pamphlet represents the challenges black activists encountered as they developed a politics that would go beyond making people free.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Great piece. So many white abolitionists claimed they were “speaking for the slave” when there were, in the movement, many escaped slaves who could very well speak for themselves. Smith’s insistence on abolition purity over real-time rights is of a piece with that paternalistic strain of white savior abolitionism that was sadly so common.