Marion Thompson Wright and Brown v. Board of Education

This post is part of our forum on Black Women and the Brown v. Board of Education decision

Marion Thompson Wright (1902-1962) is best known as the first Black woman to earn a doctorate in the discipline of history, a feat she accomplished by her dissertation, The Education of Negroes in New Jersey, completed at Teachers College/Columbia University in 1940. Wright had a distinguished career teaching from 1940-1962 in the vaunted Department of Education at Howard University. One lesser-known aspect of her career is the research efforts she made on behalf of the NAACP legal brief leading to the successful case, Brown v. Board of Education, in 1954. As this essay shows, working toward the racial integration of American schools had always been a goal of Marion Thompson Wright’s life and work.

Marion Thompson Wright’s career was devoted to proving the need for and social benefits of racially integrated schools. Her 1929 M.A. thesis focused on state expenditures for white and Black schools in the ongoing Jim Crow era, while her doctoral thesis detailed the efforts of Black New Jerseyans and their Quaker allies to create early integrated schools. This effort was only partially successful. Marion Wright attended integrated schools in Newark, while schools in the southern counties of the state were rigidly segregated. Wright’s scholarship had always highlighted the dangers of segregation and the benefits of integration for New Jersey’s Black and general population.

In the mid-1950s, Marion Thompson Wright played a key role in insuring equal access for all in New Jersey state schools through legislative reform. She chronicled these efforts from 1953-1954, in four articles published in The Journal of Negro History and Journal of Educational Sociology (JES). The articles showed how New Jersey had moved toward school integration beginning in 1941, then passed a fair employment act in 1945. The state put real power into its drive to integrate through the establishment of the Division against Discrimination (DAD), headed by Joseph L. Bustard of Roselle, New Jersey, along with veteran Black Newark activist Harold Lett. She described how the DAD organized conferences and workshops and influenced local councils. All this was preliminary to the enactment of the new state constitution with its emphasis on civil rights enforcement. As new regulations were promulgated, Wright asked what would become of Black teachers. Indeed, she noted that since they were protected under the new laws, their numbers increased with integration. All this, she argued, happened because of legal enforcement and education, pushed by local activists. Wright also published a series of follow-up articles on New Jersey’s progress in November 1953 in the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the nation’s leading Black newspapers.

Wright accomplished all this during a time of personal frustration and crisis. The summer of 1953 did not develop as Marion Thompson Wright planned. After completing a semester as interim chair of the Howard University Department of Education, she was not appointed to the regular term post. Perhaps to assuage her disappointment, Wright had hoped to travel to Europe, but the sudden decline in the health of her mother, Minnie Thompson, forced Wright from her apartment in Washington, D.C., back to the family home in Montclair, New Jersey. She had to take leave from her position as a full professor to care for her aged parent. Wright purchased the home in 1937 with her husband, Arthur Wright, even though the couple were finalizing a divorce. Arthur Wright remained there in the home, necessitating daily contact between the estranged couple. Marion Wright’s daughter from a previous marriage, Thelma Moss, was also living in the Montclair house, although mother and daughter remained on distant terms after decades of alienation resulting from Wright’s abandonment of her children in 1922. Minnie Thompson died in November 1953, two years after the death of Marion Wright’s father, Moses Thompson.

What Marion Wright did have to counter the tensions at home was her academic position. Despite the disappointment that she did not move beyond “Acting Chair,” Wright could be proud of her dozen years of accomplishment at Howard University. After earning a B. A. in 1927 and an M.A. in Education at Howard University in 1929, Wright completed a doctorate at Teachers College, Columbia University in 1940. Her mentor was the distinguished social historian, Merle Curti. Wright’s Ph.D. was the first by a Black American woman in the discipline of history. Wright then published her dissertation as a book with Columbia University Press entitled The Education of Negroes in New Jersey. She joined the Howard University Department of Education, which was one of the most distinguished in the field, in 1940, and was tenured in 1946 and promoted to full professor in 1950. She published award-winning articles in the Journal of Negro History and other venues and served as an indefatigable book review editor for the Journal of Negro Education. All the while, she was a much respected and dedicated faculty member at Howard. In 1946 she devised a counseling service for the university’s students. Wright was also highly active in national and women’s associations.

Marion Wright’s substantial visibility in the field of school desegregation likely prompted the principal investigators of a major Supreme Court case to ask for her help. From July to November of 1953, Marion Wright worked for the massive NAACP legal project that became known as Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas.

In July 1953, Horace Mann Bond asked Wright and Mabel Smythe—the brilliant deputy director of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and a future diplomat—to work with him on Fourteenth Amendment cases considered critical to the suit’s argument that segregation was unconstitutional. However, determining the intent of the framers of the amendment toward segregated schools was a tough proposition and not a settled historiographic subject at the time. Bond, Smythe, and Wright set out to prove that the state constitutions forbade segregation as a condition for readmission to the Union. Congress would have to accept or reject the states’ applications as the ultimate arbiter of an intent to have integrated schools. The research team found that with the exception of Texas, which quickly had to rewrite its application, none of the other ten Confederate states sanctioned segregation or mentioned race in connection with the public school system.

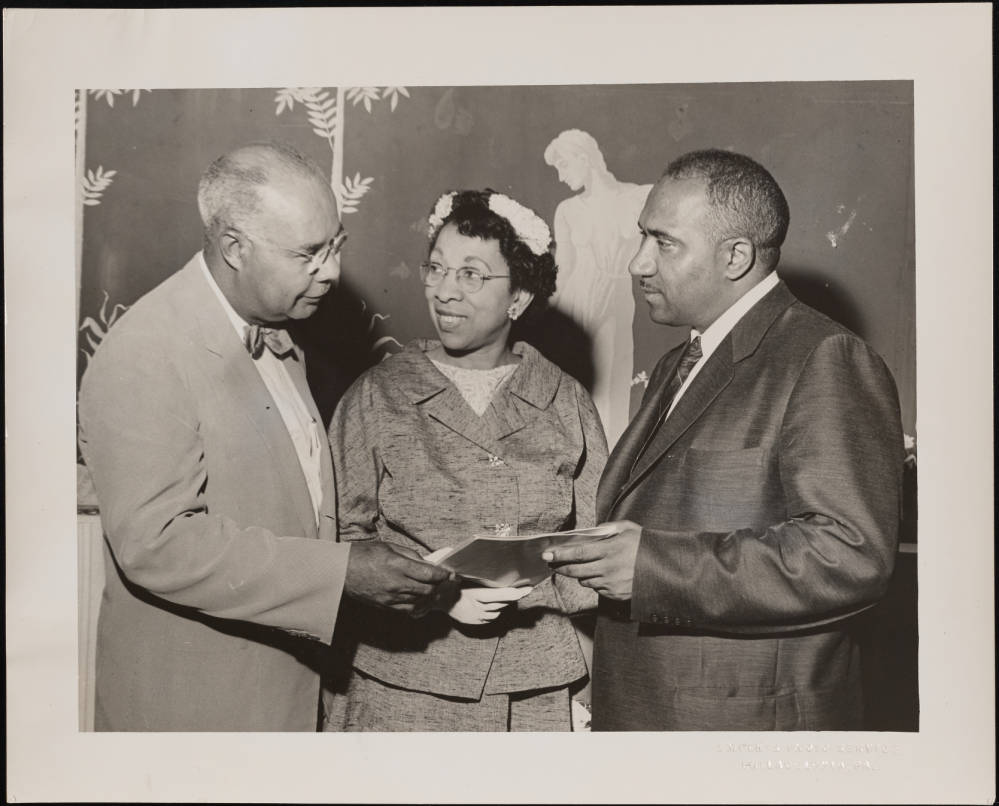

For Bond, there could be no better proof of congressional intent about school integration. There were several problems with this interpretation. First, the state governments were controlled not by diehard Confederates at this stage, but by loose alliances within the Republican Party. Second, most of the public school systems were more concerned with economic survival than the establishment of expensive separate school systems. Moreover, Black legislators were more concerned with free public systems that would serve freed people badly in need of basic learning, more so than mixed schools. Eventually the NAACP brief famously contended that separate schools inculcated a sense of superiority in whites and induced perceptions of self- inferiority among Blacks. As Wright had documented in her book and subsequent articles, those sensibilities were enhanced by decidedly unequal facilities. Ultimately the NAACP used much of the arguments by Bond, Smythe, and Wright in fourteen of the two hundred pages in its final brief before the Supreme Court. Wright was named in the final Supreme Court brief as Bond’s assistant. Wright, Bond, and Smythe presented a number of their findings early that fall in a discussion panel at an NAACP conference in New York City on September 25, 1953.

The Supreme Court of the United States determined on May 17, 1954, that the “separate but equal” philosophy governing segregated schools in the American South and elsewhere was inherently unequal. By depriving Black children of equal access to quality education, offending states violated their constitutional rights. Forced integration of public schools proved to be the primary engine of change toward an integrated society.

Wright’s research may not have been as useful to the NAACP in its initial lawsuit leading to the Brown v. Board of Education decision but may be more relevant to struggles in the present. Currently, the US Supreme Court is considering arguments made in the lawsuits, Students for Fair Admissions, Inc v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, and a similar complaint against the University of North Carolina. The complainants argue that the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits all race-conscious policies, contrary to the well-established precedent most recently affirmed in the 2003 case, Grutter v. Bollinger. An Amicus Curiae created by a number of leading historians of the Reconstruction Era to support the respondents argued that the Amendment was designed to bar states from discriminatory actions based upon race and to design, among other aspects, equal access to educational opportunities for Black people. The Reconstruction Congress supported race-based programs and rejected demands for strict racial neutrality. It wanted to reverse any Black Codes passed after the Civil War.

Here Wright’s research is useful. As she learned, citizens of Southern states were still reeling from the chaos and destruction of the Civil War. As the Fourteenth Amendment was being debated and then ratified by the former Confederate states, southern educational institutions were in despair and badly needed direction from the Federal government. Hence the Fourteenth Amendment instilled order and positive racial integration of schools. That society fell back later and lapsed into segregation occurred when localities were allowed to ignore federal edicts. Wright chronicled all this in the last chapters of her landmark book The Education of Negroes in New Jersey. Contemporary disputers over the intention of the Fourteenth Amendment would benefit from a review of Marion Thompson Wright’s historical evidence and insights.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.