James Weldon Johnson, Langston Hughes, and the Ever-Deferred Dream

This post is part of our forum on Black Intellectuals and the Crisis of Democracy.

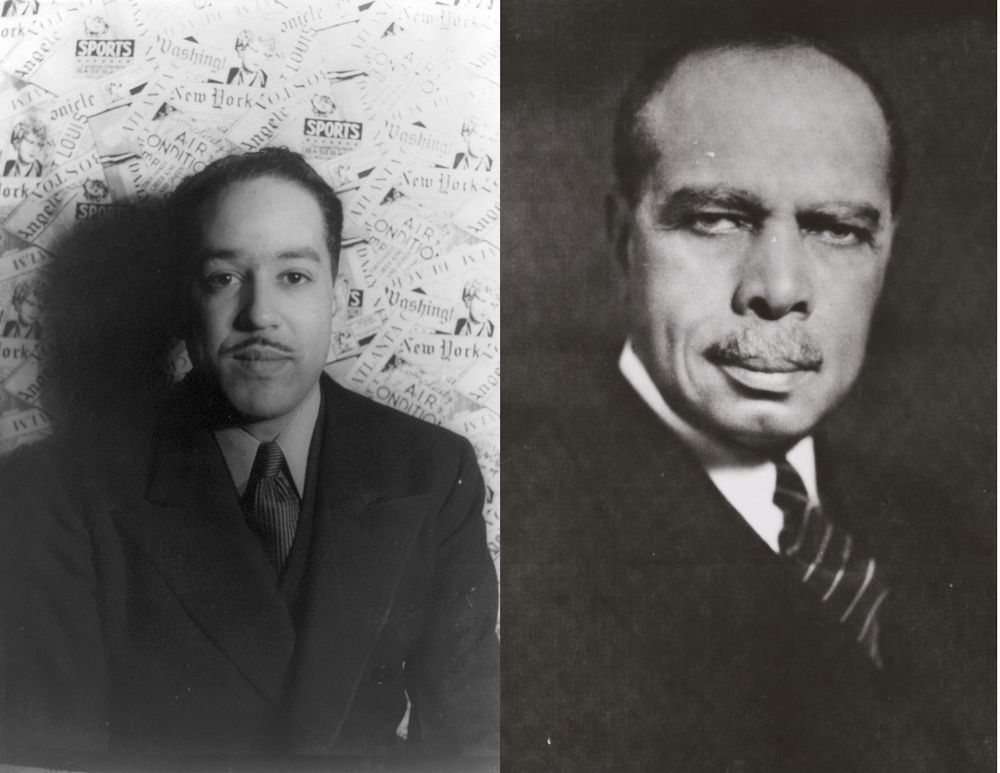

Once Africans began being forced onto ships bound for America, their self-will—their inner knowledge of their right to their own liberty—began powering their resistance to the unrelenting oppression they now faced. They and their descendants waged a “constant struggle” to overcome what James Weldon Johnson (1871-1938) described as “the unremitting pressure of unfairness, injustice, wrong, cruelty, contempt, and hate.” As Christian and liberal ideas circulated throughout the British and French empires, enslaved peoples seized the language of their oppressors to claim their liberty. In the 1770s, slaves in Massachusetts repeatedly petitioned for their freedom, protesting that “they have in Common with all other men a Natural and Unalienable Right to that freedom which the Great Parent of the Universe hath bestowed on all mankind.” Moral, republican, and legal arguments for African American rights intermingled until, with the Civil War, the most important problem in American life changed from the contradiction between democracy and slavery to the so-called Negro Problem, the question of where former slaves and their descendants belonged in the newly reunited nation, if not as fully equal citizens. When the crisis of democracy became plain after the Plessy decision (1896), Johnson, Langston Hughes (1902-1967), and numerous other intellectuals, artists, and activists emerged as voices of conscience, insight, reason, knowledge, and wit. Johnson and Hughes provide an intergenerational framing of the democratic problem that they and their cultural descendants faced: the problem of believing in democratic principles while enduring what Johnson and his friends felt in 1905. “If what we felt had been epitomized and expressed in but six words,” Johnson recalled, “they would have been: A hell of a ‘my country.’”1

Johnson and Hughes are separated by more than the three decades between their births, but they had a lot in common. On the question of this country and its democracy they fundamentally agreed, with both committing their entire lives to writing and acting in the service of the people to whom they considered themselves to belong

That is, to “Negroes,” as their era’s label boxed them, and to Americans, despite the crackers who dishonored them and the white liberals who too often let them down, and really to humanity itself. Both men had Native ancestry and were aware of their roots beyond slavery, of culture and inheritance that came from the other horn of settler colonialism. Both were fluent in Spanish and capable in other languages, and both had significant cosmopolitan experience; Johnson became an agent of empire as an ambassador to Nicaragua before the Wilson administration curtailed Black federal service, while Hughes lived with his father in Mexico for a significant spell and traveled the world first as a sailor and later as a Soviet darling. Both wrote almost as easily as they breathed, it seems, in a variety of genres: poetry and prose, for stage and song, both with important novels, and both great memoirists as well. Neither had children, but both were so richly connected that between them, they knew just about everyone involved in literary, political, artistic, religious, academic, and legal efforts to rectify the American racial problem in the decades between the failure of Reconstruction and the post-Brown era. If Johnson’s iconic “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” (1900) sound sunny while Hughes brings the clouds in “Let America Be America Again” (1936), both maintained, throughout their lives, the tension between their relentless critique of American hypocrisy and their sustaining commitment to the egalitarian ideal of the democracy America so falsely claimed to embody.

Johnson and Hughes detested segregation, which did not mean that they craved the company of white Americans. They were, however, pleased when their intellectual productions reflected “interracial collaboration and good will”—such as Hughes described a booklet of his illustrated by a white Greenwich Village artist—in the hopes that such examples “might help democracy in the South where it seemed so hard for people to be friends across the color line.” Their shared problem was discrimination and inequality before the law. As Johnson described his only wish if a genie were to appear: “Grant me equal opportunity with other men, and the assurance of corresponding rewards for my efforts and what I may accomplish.” Johnson and Hughes wanted to live in the meritocracy America claimed to be.2

Crackers were the most obvious obstacle, not necessarily those who had cracked the whip but those who had cracked their own corn and yet shunned solidarity with other victims of capitalism. Johnson identified this as “one of the paradoxes of democracy,” how his people “belong to the proletariat” and yet were shunned by labor unions. Whether the moral arc of the universe bends toward justice or not, the arc of history has no sure progression whatsoever, Johnson illustrates, he himself a witness to the decline in race relations in Jacksonville, Florida, as it transitioned from a place with Black police officers, firefighters, city councilmen, and justices of the peace to “a one hundred percent Cracker town.” Hughes indicated the same group in a Depression-era short story set in an Alabama town where “red-necked crackers” roamed the streets. Johnson, Hughes, and others knit the term cracker into the lexicon of Black liberation, a keyword later used dexterously by the likes of James Baldwin (1924-1987) and Malcolm X (1925-1965), who clarified that crackers were not confined to the South. They were right. Today, “White Boy” logos proliferate across the country and redness—on caps, maps, or necks—signifies division.3

White liberals were certainly more congenial than crackers, and Johnson is also witness to the era when their defining characteristic became an explicit commitment to racial egalitarianism. “I myself,” he attested, “have yet to know a Southern white man who is liberal in his attitude toward the Negro and on the race question and is not a man of moral worth.” Hughes, too, encountered “several liberal white students” willing to share a 1931 meal with him in North Carolina; this symbol of liberal open-mindedness—the breaking of bread together—would reappear in a short story Hughes included in his Something in Common collection of 1933. Yet white liberal courage too often failed. By 1961 Hughes was leery of “’liberal whites’ …who usually get scared if one single letter is written to the paper.” These cowardly would-be allies were the main allies Black Americans had—as lawyers, patrons, sponsors, publicists, activists, reporters, and audiences—so their critics were numerous, all sharing the same complaint. As a young Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., wrote in the New York Post about how New Deal relief bypassed Harlem, “so-called liberals…wear the round laurel wreath of liberalism upon their square heads” while acting inequitably. Black America knew then and knows now all too much about what Baldwin called, in 1972, “the chicken-shit goodwill of American liberals.”4

Johnson, Hughes, and their cohort all knew that they were better liberals than their white liberal allies—but the problem of democracy kept them engaged because giving up was never an option. They knew where they came from, and they knew what their people deserved. They remembered their foremothers’ smooth black braids and their forefathers’ service to the Union cause. They traveled the world, but they committed themselves to the nation they knew their ancestors had built. “This land is ours by right of birth,” Johnson asserted in the so-called Negro national anthem. “This land is ours by right of toil,” he insisted. Hughes said the Black thinker is “the one who dreamt our basic dream,” and included this dream “In every brick and stone, in every furrow turned/That’s made America the land it has become.” They could never quit that dream because they could never quit their ancestors.

- Marcus Rediker, The Slave Ship: A Human History (New York: Viking, 2007). James Weldon Johnson, Along This Way (New York: Da Capo Press, 2000) pp. 205-06. Christopher Cameron, To Plead Our Own Cause: African Americans in Massachusetts and the Making of the Antislavery Movement (Kent: Kent State University Press, 2014), p. 64. ↩

- Langston Hughes, I Wonder as I Wander (New York: Hill and Wang, 1956). P. 47. Johnson, Along This Way, p. 136. ↩

- Johnson, Along This Way, p. 45. Langston Hughes, The Ways of White Folks (New York: Knopf, 1933), p. 219. ↩

- Johnson, Along this Way, p. 142. Hughes, I Wonder As I Wander (New York: Hill and Wang, 1956), p. 46. Arnold Rampersad and David Roessel, ed., Selected Letters of Langston Hughes (New York: Knopf, 2015), p. 367. Allon Schoener, ed., Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America 1900-1968 (New York: The New Press, 1968), p. 136. James Baldwin, Collected Essays (New York: Library of America, 1998), p. 377. ↩