Howard Thurman’s Jesus and the Disinherited as a Framework for Victory

This post is part of our forum on Howard Thurman and the Civil Rights Movement.

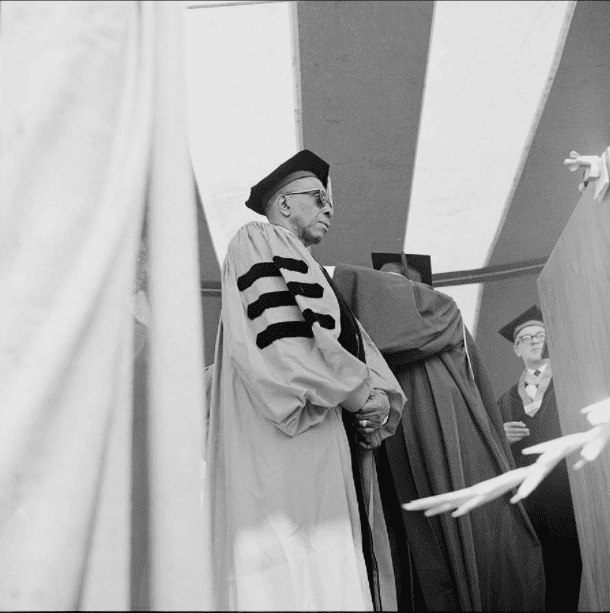

Howard Thurman (1899-1981) was a preacher, mystic, philosopher, and civil rights activist, whose philosophical thought advocated for non-violent activism through the building of community. Thurman’s philosophy of non-violent activism influenced civil rights leaders such as Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who often carried with him a copy of Thurman’s most well-known work, Jesus and the Disinherited. Jesus and the Disinherited is a treatise for addressing the complex issues regarding racial segregation, but it also seeks to offer hope to the disinherited. There is much that one can draw from this important work as a framework for victory over oppressive forces.

Through his analysis of the life of Jesus, Thurman seeks to bring hope to a class of people—in this context, African Americans—who have been placed at the margins of society. Thurman’s connection to the life of Jesus is one that is foundational to the premise of the work. It is important to note that Thurman draws a distinction between Christianity and the religion of Jesus, not only in Jesus and the Disinherited, but in his other works as well. Thurman’s conceptualization of Christianity is one in which he sees it as being exclusionary, especially for those who are of the disinherited group, while he sees the religion of Jesus as being inclusionary of all. This inclusionary status is the foundation for Jesus and the Disinherited, as he sees the life of Jesus as being a framework for liberation of the disinherited.

The connections that Thurman draws between the life of Jesus and the experiences of African Americans presents the idea that, even though the disinherited have been oppressed, there is a place of freedom that is attainable. Specifically fear, deception, and hate have placed African Americans in a place of mental imprisonment, which has oftentimes lodged itself within their psyche. Thurman sees fear as oppressing the disinherited, and it is through the life of Jesus that he sees a remedy for addressing this fear. Fear within the lives of the disinherited is rooted in the oppression and violence that they face. As a result of this oppression—which is often accompanied by violent acts against the disinherited class—there is an outgrowth of fear. Within the experiences of African Americans, one can see evidence of this outgrowth of fear.

Thurman discusses the connection between fear and deception. This deception is based on how the races view each other. For Thurman, deception is both the root of racism and a direct response to racism. He views deception as the root of racism because of how the group in power views the disinherited, and he views deception as a direct response to racism in how Thurman views the disinherited as seeking to secure their victory, with the disinherited seeking to obtain their victory by any means necessary. This is because there cannot be an honest and organic exchange between the group in power and the disinherited. Deception is seen as being a circular event that affects the disinherited in a myriad of ways.

In Jesus and the Disinherited Thurman examines the effects of hatred, and how hatred is tied to lack of community. Thurman sees how one can more readily hate someone that they do not know, and segregation provides conditions where unfamiliarity can lead to hatred. He notes that hatred is not solely referring to the relationship of the group in power towards the disinherited. It is important to note that Thurman sees hatred in the feelings of the disinherited towards the group in power, as the oppressed often operate from a place of hatred toward the group in power. This is also evident in the ways that the oppressed group views themselves. Thurman brings into the discussion that, as hatred is such an insidious concept, one should look to the life of Jesus for a blueprint. He gives the example from the life of Jesus regarding how to deal with hatred, as Jesus’s rejection of hatred serves as the example for the disinherited, as He knew that hatred is a destructive force that will eventually destroy those who choose to carry it in their hearts.

Thurman brings his discussion full circle with his philosophy on love. Central to Thurman’s philosophy is that love is part of the religion of Jesus. Within the religion of Jesus, according to Thurman, there is the foundation of loving one’s neighbor. Thurman notes how the religion of Jesus places a premium on how an individual must first love God, and then love their neighbor. Of note is how he discusses the ways in which Jesus faced opposition in this way of love, especially in the application of this way of love towards those who opposed Him. For African Americans, Thurman draws a similar connection, noting that they will face similar opposition if they choose to love those who oppress them, as it is not seen as a logical reaction to oppression. Most often the expected reaction is for the oppressed to fight back and hate their oppressors. In Jesus and the Disinherited, Thurman offers love as a solution. For African Americans to realize self-worth and self-love, he sees it necessary to change how they view whites. Instead of seeing whites as the enemy, there must be a shift towards seeing them as brethren. Thurman’s argument in this is that it empowers African Americans to exercise agency, rather than allowing a continual oppression through fear, hatred, and deception. To put this into practice, there must be proximity to one’s fellow human, and segregation cannot offer this.

An examination of the significance of Thurman’s Jesus and the Disinherited offers some important implications for the civil rights movement. Love as a foundation for liberation is one of the ethics of the movement, as this was a pillar of the non-violent activism of leaders such as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and James Farmer. Thurman’s philosophy provides an alternative response to hatred, which empowers the disinherited toward a path of victory over the mental bondage that racism has imposed over African Americans. Thurman’s philosophy of love in Jesus and the Disinherited and his other works argue that love as a response to hatred—which is not the expected response—can free the disinherited from this mental bondage. This not only helped to shape the civil rights movement but is a valuable tool for the liberation struggle for African Americans today.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Is there a role for a living God in Thurman’s work? Always seems to reduce things to matters of psychology/recognition in a somewhat Hegelian way but without the sense of a guiding Spirit.

Thank you for your comment. Yes, there is a role for a living God in Thurman’s work, as he sees cultivating a life that is led by the Spirit as foundational to how one operates in other areas of their life. I would recommend looking at his book, Disciplines of the Spirit.

thanks I’ll check that out, was he influenced by Josiah Royce?

Great contribution to this series. Important distinction between Christianity and the Religion of Jesus. The influence on Dr. King and the Civil Rights Movement is very noticeable.

Thank you so much!