Highways, High-Rises and Food Deserts

This is the second part of our series about Race and DOCUMERICA.

For many DOCUMERICA photographers, images of Black life were at best an incidental or marginal part of their larger assignments for the Environmental Protection Agency. In some cases, location helped to shape such disparities. Even into the 1970s, African Americans constituted less than one percent of the total population in states such as Maine, New Hampshire, Idaho, Utah, and North Dakota. However, it was also common for assignments which focused on more racially diverse states or cities to contain few images of Black life; a trend that was likely a result of the preponderance of white photographers among the project’s contributors.

The most striking exception to this trend was an assignment by the Chicago-based African American photojournalist John H. White, who chose to intentionally center the city’s African American community in his contributions to DOCUMERICA. In truth, it is hard to overstate the significance of White’s work for the EPA vis-à-vis Black representation, with close to half of the photographs I have cataloged through my digital history project This Land is Your Land coming from White’s portfolio. White’s assignment is even more impressive when we consider that he was still a relative newcomer to the Windy City; the photographer had relocated from North Carolina during the late 1960s to take up a role at the Chicago Daily News. Approaching its fiftieth anniversary, White’s DOCUMERICA assignment remains a remarkable achievement – a vivid, complex and intimate portrayal of the nation’s second largest Black urban community in all its sprawling diversity and complexity.

Many of White’s images offer a joyous, celebratory documentation of Black life in Chicago; perhaps none more so than his documentation of the 1973 Bud Billiken parade, a well-established and hugely popular South Side tradition that will be the focus of my next essay for Black Perspectives. However, his DOCUMERICA assignment also endures as an important visual record of urban inequality. More than a decade before the concept of “environmental racism” became entrenched in activist, academic, and policy circles, White’s work for DOCUMERICA forcefully highlighted growing economic and social disparities between disproportionately Black and poor inner-city communities in Chicago and disproportionately white and middle-class suburban neighborhoods outside of the city’s ‘urban core.’

These disparities were exacerbated by the racially disproportionate impact of postwar urban renewal and infrastructure projects, which uprooted African American communities across Chicago and in particular on the South Side, the beating heart of the city’s ‘Black Metropolis.’ Following the passage of the 1956 Federal Highway Act, which provided tens of billions of dollars in funding to build new expressways across the country, Chicago joined other major cities in developing a network of “super-highways.” The crown jewel of Chicago’s new transport network was the Dan Ryan Expressway, a twelve-mile stretch of freeway designed to connect commuters from the city’s southern suburbs to its downtown business district. While mayor Richard Daley championed the Dan Ryan as a crucial piece in his plan for a “new” Chicago, the freeway had a devastating impact on many South Side communities, displacing thousands of African American residents and creating a physical barrier between poor Black neighborhoods along the State Street corridor and the whiter and more affluent neighborhoods of Bridgeport and Canaryville. Daley’s biographers Adam Cohen and Elizabeth Taylor contend that the Dan Ryan was “the most formidable impediment short of an actual wall that the city could have built to separate the white South Side from the Black Belt.” White’s images of the Dan Ryan capture this sense of displacement as well as the sheer scale of the project.

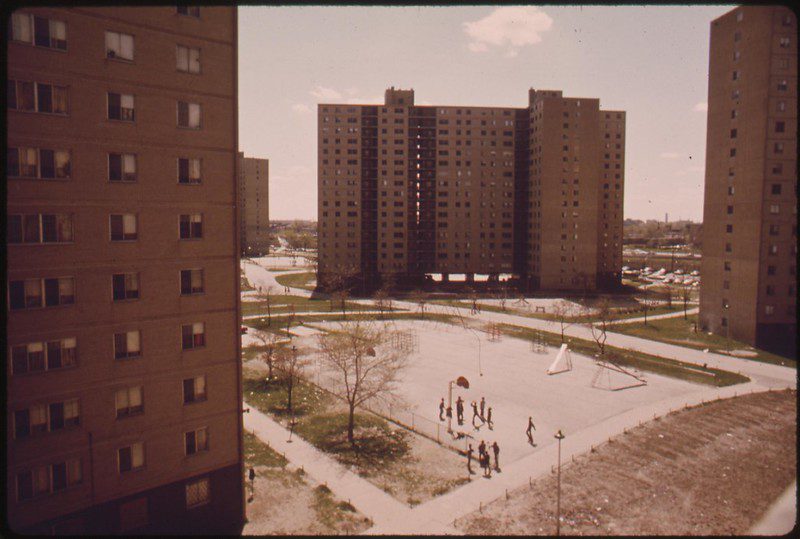

Many of the Black families affected by the construction of the Dan Ryan found themselves warehoused in one of five public housing projects erected parallel to the expressway along the State Street corridor. It was the largest concentration of public housing in America. Just as the development of the city’s highway system was celebrated as a pathway to a better Chicago, the largescale construction of public housing was seen as a way of uplifting the city’s marginalized communities. However, echoing opposition to freeway location, white backlash to the proposed siting of public housing led to these developments being concentrated in Black communities. As a result, instead of helping to uplift Black Chicagoans, this huge tract of public housing exacerbated the problems created by the construction of the Dan Ryan and other expressways, contributing to “the obliteration of older black neighborhoods in the urban core, the destruction of African American businesses and households, [and] the forced relocation of countless individuals.”

Chicago’s public housing projects loomed both literally and figuratively over White’s portrait of Black Chicago; most notably the Robert Taylor homes, a series of 28 identical 16-story high-rises stretching from 29th to 54th Street, and Stateway Gardens, a complex of eight buildings ranging between ten and seventeen stories located between 35th Street and Pershing Road. White’s images powerfully illustrate the debilitating combination of confinement and isolation created by these structures, with Rashad Shabazz suggesting that, for many CHA residents, Stateway Gardens and the Taylor Homes came to represent “the spatial and architectural marriage between home and prison.” The photographer’s lens highlights the carceral uniformity of the project and the city’s failure to redevelop much of the surrounding land, marking each project as a “hypersegregated island.”

The barren urbanscapes of Chicago’s postwar public housing were indicative of a broader “hollowing out” of Black neighborhoods on the South Side during the 1970s, as many middle-class African Americans followed white Chicagoans into its rapidly expanding suburbs. This human migration was accompanied by the business relocations, further redirecting economic and political power away from the ‘urban core’ and leaving many Black communities without access to basic amenities. One impact of this trend can be traced through the suburbanization of grocery and supermarket chains – between 1970 and 1990, Chicago lost more than half of its total supermarkets, depriving many inner-city Black residents of access to fresh groceries. As these businesses moved out of Black neighborhoods, liquor stores and fast-food franchises moved in. Complementing work by scholars such as Marcia Chatelain, Chin Jou and Keith Wailoo, White’s images reflect how a new visual geography of Black urban life had taken hold by the early 1970s – one characterized by tobacco billboards and chicken shop and liquor store signs. This geography had devastating health implications. Just as damaging, it quickly became a visual short-hand for a ‘failure’ of personal responsibility, with liquor stores and fast-food joints joining the high-rise and freeway as signifiers of racialised poverty and marginality in the landscape of the post-industrial American city.

By documenting such problems, White’s DOCUMERICA assignment placed Black Chicagoans at the heart of ongoing debates around the ‘urban crisis’ and powerfully demonstrated how the lived experiences of inner-city Black residents was shaped by the environment around them. When read in isolation, many of White’s images offer a bleak, almost nihilistic account of Black urban life, with spiraling rates of unemployment leaving formerly vibrant Black neighborhoods as “a wasteland of empty storefronts, burned-out buildings, and vacant lots.” This nihilism is perhaps best captured through a photograph of a young Black man sitting on the windowsill of an abandoned South Side building. White’s caption informs readers that the man “has nothing to do and nowhere to go.” For many Black Chicagoans, bombarded by continued disinvestment, economic malaise, and neighborhood decline, this was a familiar story. However, as many of White’s other images show, and as the next installment of this series will articulate, this was far from the only story.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.