Constructions of Africa in Early Soviet Children’s Literature

This post is part of our online forum, “Black October,” on the Russian Revolution and the African Diaspora

The political and social changes brought on by the October Revolution of 1917 permeated nearly every aspect of Soviet life. The Communist state assumed the role of guardian, protector and nurturer, and the moral upbringing and education of children took on particular significance. For Soviets, the task of shaping moral sensibilities required instilling a sense of solidarity with, and sympathy for those oppressed by Western political and economic systems. In particular, Western racism and colonization in Africa provided a rich opportunity to critique the exploitation of the continent. Children’s literature became an important tool in nurturing values and political sensibilities in the state’s youngest citizens. In particular, early Soviet works depicting Africans and people of African origin highlighted racial and economic injustices perpetrated on the continent but also reinforced pejorative attitudes about Africa. Works such as Kornei Chukovsky’s Barmaley (1925) posited a dark Africa, wild and foreboding, a place to be avoided. These attitudes continued to resonate and form the basis of a complicated relationship between Russians and Africans during the Soviet period.

In children’s literature published just prior to and in the decade following the October 1917 Revolution, Africa captured the creative imagination of several Russian children’s writers. Despite the Soviet Government’s critique of Western racial oppression and colonialism, the cultural establishment drew on primitivist tropes and discourses of Black racial inferiority in their imaginings of Africa. The 1920s are particularly interesting given that it was a decade which saw a level of artistic freedom, innovation and creativity that essentially disappeared in the 1930s with the formation of the Union of Soviet Writers and the adoption of Socialist Realism as the party’s driving artistic principle. Writers who did not belong to the official party found difficulty in getting their work published. Many fell victim to Stalin’s purges and were either executed or perished in Soviet labor camps.

By the October 1917 Revolution, nearly ninety percent of the African continent had been colonized. Some Soviet children’s writers confronted human and material exploitation in Africa while others pointed to the absence of civilized development and the ongoing “white man’s burden” that placed intervention in the context of humanitarianism. These narratives underscored the flaws of Western ideologies and strengthened the Soviet Union’s moral position in its political and ideological conflicts with the West. Soviet writers contested the exploitation of Africans yet simultaneously displayed a distinct ambivalence regarding their intelligence and humanity. In contrast to nineteenth-century colonizers and slaveholders, benevolent, color-blind Soviets became alternative civilizing agents. What resulted were children’s texts that often reflected negative racial stereotypes, and with varying degrees of subtlety, reinforced centuries-old pejorative notions of what constitutes “Africa” and “Africanness.”

Arguably the most iconic image of Africa in Soviet children’s literature appears in the poem Barmaley (1925) by Kornei Chukovsky, the popular Soviet children’s poet and highly regarded translator of foreign children’s books into Russian. In Barmaley, the Russian pirate Barmaley seeks conquest in Africa. His viciousness is such that the entire continent should be avoided for fear of an encounter with him. The poem begins:

“Little children!/ For nothing in the world / Do not go to Africa/ Do not go to Africa for a walk!// In Africa, there are sharks,/ In Africa, there are gorillas, / In Africa, there are large/ Evil crocodiles/ They will bite you, / Beat and offend you// Don’t you go, children, / to Africa for a walk/ In Africa, there is a robber,/ In Africa, there is a villain,/ In Africa, there is terrible/ Bahr-mah-ley!// He runs about Africa/ And eats children-/ Nasty, vicious, greedy Barmaley!”

Yet Barmaley, for all of his viciousness, is not the narrative’s main threat; the main threat is Africa itself. The Africa of Chukovsky’s poem evokes notions of the dark, dangerous “other.” This threat is brought closer to the young reader by the suggestion that Africa as a physical space is not abstract and faraway, but is rather a place a child could encounter simply by walking (“Do not go (walk) to Africa”). Its wildness is not controlled or confined to zoos and habitats; it literally embodies the entire continent.

In spite of the narrator’s admonitions, and the parents’ warning (“Africa is terrible, yes, yes, yes. Africa is dangerous, yes, yes, yes. Never go to Africa.”), Tanya and Vanya leave Leningrad to discover Africa for themselves. What they encounter draws upon stereotypical images that construct Africa as a continent of exotic vegetation and menacing animals that roam freely. The children do not encounter African natives yet the reader retains an impression of Africa as foreboding and inhospitable, primarily on the basis of its physical topography. Barmaley, written after the historic events of 1917, lacks a direct political message. It is a fantastic tale whose aim is to entertain, encourage obedience and perhaps frighten a little. Yet the negative image of Africa has been a lasting one. It falls along a continuum of intellectual thought that can be traced back to the 19th century and pejorative Russian attitudes towards Africa and Africans.

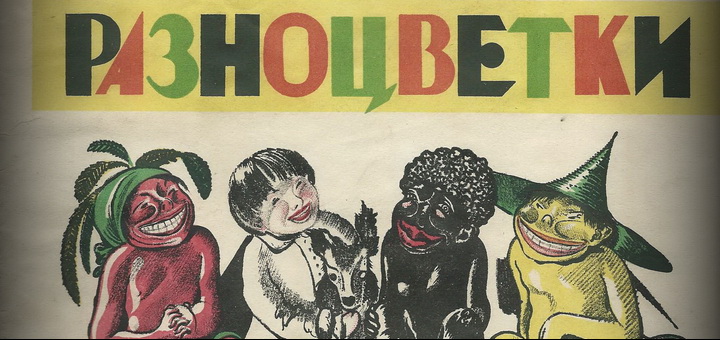

Most of the writers who produced early Soviet children’s texts that included constructions of Africa did not achieve the same level of popular success as Chukovsky, yet their work is no less important for understanding the various literary contexts in which the depiction of Africa was seen in early Soviet children’s literature. Semen Poltavsky’s Multi-colored Children (Detki Raznotsvetki, 1927) is noteworthy given its particularly grotesque visual images that reinforce the notion of Africa as the “other.” The young Soviet hero Vanya builds a plane and embarks on a trip to visit representatives of the world’s four races. Poltavsky’s narrative does not address the issues of European colonialism or western racism, but it does pose a broader question of cultural superiority. At first glance, the reader sees a young, physically appealing Soviet child who simply desires adventure. Yet increasingly offensive racialized caricatures are introduced that reflect the perceived cultural superiority of Vanya and suggest a racial hierarchy that places Africans squarely at the bottom.

In their depictions of Africa and people of African origin, Soviet children’s writers frequently reinforced stereotypes that may ultimately have had, however unintentionally, a negative impact on how Soviets perceived people of African origin. One example from Soviet popular culture would be the song “Chunga Changa.” Made popular by the animated film Katerok (1970), “Chunga Changa” presents Africa as a land of exotic animals and carefree, banana-eating natives whose primitivism is idealized. But this presumably positive view of Africa has a clear, patronizing subtext.

Ongoing political and ideological conflicts and the drive to expand spheres of influence in Africa provided an ideal background for Soviet writers’ negative literary portrayal of exploitative economic systems. Within this context, Soviet children’s writers highlighted the historical discrimination against Africans and contrasted it with the Soviet ideal of international brotherhood and equality. Yet the use of pejorative images of Africans arguably contributed for the racism many Africans experienced in the Soviet Union throughout the Soviet era.1

Soviet Communists touted solidarity with their oppressed brothers across the globe, and equality was held up as an ideal, but children’s literature of the 1920s reveals how some brothers were more clearly equal than others. The ramifications of how this played out in practical terms were seen in the lived experiences of many Blacks in the Soviet Union for years to come. The 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution provides an opportune moment to reconsider the crucial role of children’s literature, not only in the socialization process but also in the formation of racial attitudes. In a broader context, it also provides a moment to reflect on how the Russian Revolution fell short of its promise of racial equality in the Soviet Union and on the continued pervasive effects of internalized racial attitudes.

- Although many Africans and African-Americans had successful and contented lives in the Soviet Union, their experiences were not universal. Several soviet historians have written on African experiences of experiences with racism in the Soviet Union. For an excellent examination of this history see Maxim Matusevich’s, Africa in Russia, Russia in Africa: Three Centuries of Encounters. Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press, 2007 ↩