Black Resistance, Historical Memory, and Monuments

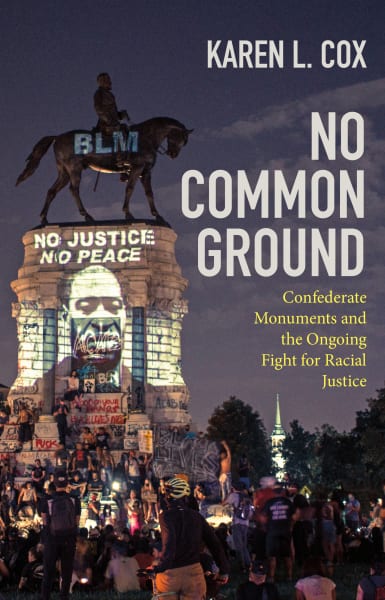

While commentators often point to 2015 (after the Mother Emmanuel shooting) or 2017 (after the Charlottesville terrorist attack) as the starting point for protests against Confederate monuments, African Americans have opposed Confederate monuments since they were erected. Indeed, monuments have been a central gathering place for Civil Rights protests and the defacing of monuments has a history almost as old as the monuments themselves. A study of both Confederate monuments and the activism against them was sorely needed. Fortunately, having already written the book (literally) on the United Daughters of the Confederacy, Karen Cox, a professor of history at the University of North Carolina Charlotte, decided to write a history of Confederate monuments. Scholars and the public will be thankful she has. Building on her earlier work Dixie’s Daughters, Cox’s No Common Ground: Confederate Monuments and the Ongoing Fight for Racial Justice focuses on monuments and their afterlives.

The book argues that “monuments are part of a longer history that is also mired in racial inequality and modified by black resistance” (2). Cox demonstrates how “monuments are not innocuous symbols” (3) but are instead part of the systemic racism that harms American society, although she is careful to point out removing them does not solve racism; instead it may “serve as an important first step” (4). In other words, protests about monuments are not an endpoint in the fight for racial justice but part of a much broader struggle. Indeed, in that context the book seeks to see how monuments became both “flashpoints in the crusade for white supremacy as well the struggle for civil rights” (8).

Cox first explains how the American South got so many monuments to a defeated army. The first chapter introduces readers to the Lost Cause and how monuments were erected not to “preserve history but to glorify a heritage that did not resemble historical facts” (13). Central in this book and other recent work on the Lost Cause has been a focus on the role race, racism, and white supremacy played in the Lost Cause and monument-building movement. As Cox aptly argues in the second chapter, “while the foundations for monument building […] were originally based in bereavement and remembrance, the Confederate generation quickly infused monument dedications with a defiant Lost Cause rhetoric about the justness of secession, the superiority of southern civilization, and the necessity of preserving the racial status quo in the absence of slavery.” In examining the purpose of the Lost Cause, Cox concludes that “those committed to the Lost Cause were, in essence, committed to a new form of southern nationalism that invoked white supremacy” (29-30). This is just one of the key arguments of the book: the Lost Cause was not just about what happened in 1865 but about what happened after.

White supremacy has been upheld by the Lost Cause in a variety of evolving ways. For example, today claims that the war was not about slavery are used by neo-Confederates to detach the Confederacy from racism. But that wasn’t always the case, Cox explains. Arguments that the war was about states’ rights and not slavery were openly tied to white supremacy when many monuments were erected in the Jim Crow South. Cox notes “the white South’s unceasing loyalty to the principle of states’ rights which in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries meant the right to maintain a system of segregation based on white supremacy” (46). The rewriting of the cause of the war was not just so Confederates could present themselves as victorious but so they could uphold white supremacy. Confederate symbols have long been attached to white supremacists politics. Indeed, from their creation. And Cox shows how these ties between racism and Confederate memory have only strengthened and grown since their Civil War origins.

In the last few years there has been an increasing need for accessible writing about Confederate monuments that brings the story to the present, and Cox helps fill that gap. This book is part of a wave of new scholarship reconsidering the Lost Cause not just as a historical narrative that facilitated reunion in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century but one that is specifically premised upon white supremacy and fabrication. Additionally, a growing focus by scholars and the public on the pernicious impact the Lost Cause continues to have on contemporary America nationwide makes this an especially timely book. Cox demonstrates how the Lost Cause is a “fabricated account” that has been used as a tool of oppression while a counter memory “based in fact” often overlooked by scholars but recalled by African Americans across the South to push back against white supremacy (174). This helps explain the title: for how can you find common ground when you disagree on basic facts?

Unlike many early studies of Civil War memory that end their narratives in the first half of the twentieth century, Cox carries the story all the way to the protests during the summer of 2020. Indeed, the third and fourth chapters, “Confederate Culture and the struggle for Civil Rights” and “Monuments and the Battle for First Class Citizenship,” focus on the role of monuments in the Civil Rights era, before moving on to how debates about removal evolved as African Americans gained increased political power in the fifth chapter, “Debating Removal in a Changing Political Landscape.” The final chapter and epilogue examine contemporary fights (2015-2020) over monuments. Tracing the battles over historical memory and the part Confederate monuments played in the Civil Rights movement may be the part of the book that scholars of historical memory will find the most innovative and exciting.

One of the most important aspects of this book is that it doesn’t just examine white narratives of history but actively examines African American counter memories of the Confederacy. As Cox explains “to fully understand [monuments’] history is also to understand how generations of black southerners have demonstrated their scorn for monuments they have always believed were symbols of slavery and oppression” (8). Cox shines light on the many various ways that African Americans resisted the Lost Cause and points a way forward for other scholars. Indeed, after reading this I could not help thinking how much more research is still needed about African American memory of the Civil War. While Cox discusses how black Southerners fought back against Confederate monuments, she points out that black Southerners also had their own forms of remembrance, reminding scholars of the American South that African American memory remains in desperate need of further study.

The footnotes are full of excellent primary sources, many of which have been largely overlooked by previous scholars. Seeing the types of sources she uses (newspapers articles, oral histories, city council minutes, etc.) will likely help anyone trying to research the history of their own local monument, although at times more frequent references to secondary literature in the notes might have helped readers wishing to learn more about some subtopic or idea they read about in the body of the work. I suspect this was a product of the book’s target audience and intended to reduce length and cost; and it worked. At just $24.00 (for hardback!) and 206 pages this book is affordable enough and short enough to be assigned to undergraduates.

When UNC created the Ferris and Ferris imprint (of which No Common Ground is one of the first books published), it aimed to create “high-profile, general-interest books about the American South” and this book fits the bill perfectly. Well researched and with clear prose, the book was a pleasure to read. It will be perfect for the undergraduate classroom, but graduate students, scholars in the field, and the public more generally will also enjoy it. Scholars of historical memory and the American South will need to read it as well as activists interested in removing monuments. Illustrated with rarely seen pictures of Confederate monuments as points of social conflict, the book is an easy-to-read introduction to the battles over monuments that continue around America—and indeed the world—to this day.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.