Black Atlantic Journeys in the Digital

*This post is part of our roundtable “Digital Black Atlantics.”

“What would it mean to read diaspora spatially? How might an examination of the nature of movement, the travel itineraries undertaken, the borders crossed, the routes navigated, allow us to better understand the intellectual movements that were born out of mobility or lack thereof?” These questions frame my first digital mapping project, Digitizing Diaspora. When I began this work around 2014, there was already a rich body of scholarship that examined diaspora as a spatial phenomenon, highlighting the geographic dimensions of the histories, practices, cultures, and thought that make up Black expression and Black life. Paul Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic, Brent Hayes Edwards’s The Practice of Diaspora, Tiffany Patterson’s and Robin Kelley’s “Unfinished Migrations” all provide a critical apparatus for thinking about space, place, and the violence that sometimes occasioned the circulation of people and ideas in the Atlantic world.

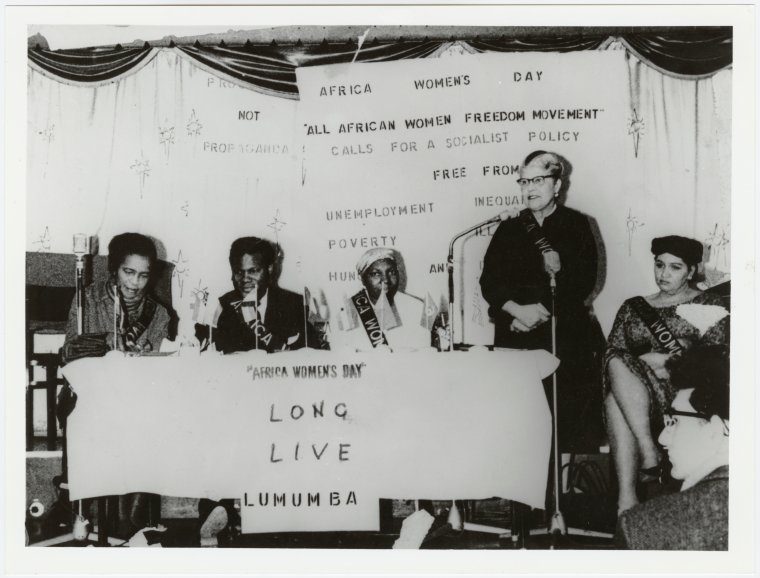

But it is one thing to think diaspora and the Black Atlantic spatially. It is another thing entirely to visualize that space, to represent its shape that is both concrete and amorphous, both triangular and not. Digital mapping offered the possibility for a dynamic visualization that would follow the confluences, breaks, and interruptions that characterized the mobility of Black thinkers and activists in the 20th century. Digitizing Diaspora’s first exhibit, Congo Diary: Eslanda Robeson’s Second African Journey charts African American anthropologist and civil rights activist Eslanda Robeson’s travels through Central Africa in 1946. Bringing together sometimes far-flung archival materials, the digital map allows users to visualize all that was potentially subversive about Black women’s travel and mobility across colonial borders. Robeson’s journey in particular, highlights important connections between decolonization processes and the making of diaspora.

The questions that motivated Digitizing Diaspora continue to animate my thinking about what digital maps can enable in our thinking. My more recent work, Mapping Marronage, draws on the core definition of the word in Black Atlantic history: the process of removing oneself from slavery. Mapping Marronage visualizes flight as process, as lived reality and as relationship to space and power in slaveholding societies. Concretely, marronage on this map is any act by which an enslaved person seeks to move him/herself beyond the reach of slaveholders’ power. Enslaved women, men and children sought to move – with varying degrees of success – beyond the reach of slavery’s oppression and dehumanization. The oppressive and far-reaching power of slavery meant that movement in and of itself did not automatically constitute resistance or marronage. Rather, the different forms of coerced and voluntary movement that characterized the circulation of enslaved people through the Atlantic world show conditions and experiences of enslavement that widen our field of vision beyond the plantation. These varying forms of mobility, including flight, correspondence, financial remittances, and legal disputes, form the core data for this visualization.

Digital mapping offers many promises. Both Digitizing Diaspora and Mapping Marronage have sought to collate primary documents scattered across far-flung archives. Recent archival closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic have underscored the need for this accessibility. As the student visualizations in this forum have beautifully illustrated, the digital map offers much. It can be a teaching tool, a research aid, an archival repository, a site for collective work and conversation. But digital maps have their limitations too. Some of those limitations are practical concerns about the time and financial investment required for sustainability. Others are more abstract concerns about privileging access, revelation, and visibility when representing the covert movement and “strategies of undersight” that enslaved people employed to fly under their enslavers’ radars. The digital beckons as a site for thinking and representing and articulating Black pasts, presents, and futures. As this forum shows, it is both generative and fraught.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.