Archiving While Black

Among the things 2018 will be known for is mainstream culture’s realization that white Americans use the police to challenge Black entry into presumed white spaces. Countless viral news stories detail how the police have been called on Black people cooking, shopping, driving—basically for existing while Black. “BBQ Becky” memes aside, at the core of this public discourse is irrefutable evidence that a Black body doing anything in a presumed white space is at best out of place and at worst a threat. Attention has been rightly focused on the surveillance of Black people in visible public spaces. However, this issue also extends to less publicly visible spaces such as the historical archive. While not traditionally considered part of the public purview the archive, and Black marginalization within it, has important implications for both scholarly and popular ideas about history.

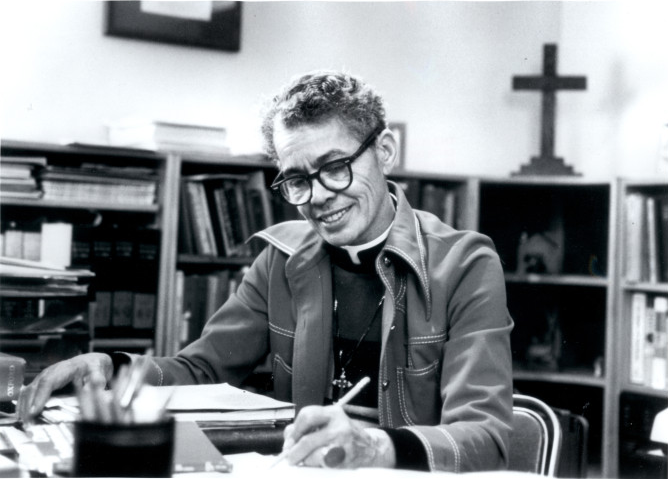

The experience of archiving while Black was perhaps best captured by famed African American historian John Hope Franklin. A native of Oklahoma who came of age during Jim Crow, Franklin experienced a series of formative racist incidents that led him to pursue a career in history. In his 1963 essay, “The Dilemma of the American Negro Scholar,” he described his efforts to view collections at the State Department Archives in North Carolina. Franklin recalled:

My arrival created a panic and emergency among the administrators that was, itself, an incident of historic proportions. The archivist frankly informed me that I was the first Negro who had sought to use the facilities there and as the architect who had designed the building had not anticipated such a situation, my use of the manuscripts and other materials would have to be postponed for several days, during which time one of the exhibition rooms would be converted into a reading room for me.”

Not only does Franklin’s reflection indicate that Black people were both literally and metaphorically shut out of the historical profession, but it also shows that the very act of archiving while Black created a panic akin to those we see when Black people occupy certain spaces today. Indeed, it was never assumed that a Black person would, in Franklin’s words, have “the capacity to do research there.”1 This issue of capacity that Franklin spoke about was an index of the racist ideas at the time. However, at the core of this claim, and the panic over his physical presence in the archive, was the fact that neither architect or archivist had ever conceived of a Black person as intellectual or that they could or should inhabit such scholarly spaces.

Propelled by these experiences, Franklin made it his goal to “weave into the fabric of American history enough of the presence of Blacks so that the story of the United States could be told adequately and fairly.” In pursuit of this goal he became one of the foremost historians of Black history, producing seminal texts such as From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans in the United States and educating a new generation of historians at institutions such as Fisk University, the University of Chicago, and Howard University.

More than half a century later, Black historians often have similar experiences of feeling out of place in the archive. Many can recount an archivists’ sense of surprise when they confidently move through archival spaces or are already clear about the procedures and regulations of the archive. If it is not one of the few archives dedicated to Black history, there is sometimes confusion about which collections historians of Black history want to access. Perhaps most universal is the weight of being the only person of color in the room surrounded by images and artifacts of America’s favorite colonizers while waiting for the staff to bring out research materials. If the architects of the archive had not “anticipated [the] arrival” of Franklin in either the building or the historical profession, then subsequent developers did not design the institution with inclusivity of non-white scholars in mind.

As waves of anti-bias conversations sweep the nation in the wake of “while Black” incidents, it’s important to interrogate how this can shape academia and, in particular, spaces of research such as the archive. At colleges and universities, we often try to remedy the lack of inclusion by focused hiring, diversity measures, and new admissions policies. Increasing numbers is one way to address the problem of Black people seeming “out of place.” Yet, as Franklin’s experience shows us, even if the doors to the university are open, scholars of color are still seen as out of place in many of the spaces that support academic research and advancement.

Rather than accept this marginalization scholars, archivists, and activist alike have challenged the very idea of “the archive”—or the privileging of certain types of artifacts as the “correct” form of historical evidence.2 Others have critiqued the institution of the archive itself, including how we house, prioritize, and categorize collections. They have also questioned attempts at diversifying the archival profession without addressing the biases embedded in the creation and physical space of the archive itself. At the core of these claims is not only a concern with individual interactions in the archive akin to Franklin’s, but also the need to address larger questions about the biases built into the structural architecture of the archive itself.

Ultimately, what scholars like Franklin are suggesting is that Black exclusion from archival spaces is more than simply a debate about physical academic space. It’s about building a more capacious foundation on which our shared histories are constructed. In the past year alone, many have identified history and, more specifically, the misremembering or misconstruing of the past, as the source of racism and political strife. Moreover, scholars, activists, and pundits all posit that historical education, accurate preservation, and a true reckoning with the past as the critical first step to moving beyond facile understandings of race in this country. However, we have to ask ourselves how we can move forward with this goal when the very act of recovering this history continues to thrive without considering Black and brown people as part of the architecture of historical research and when archiving while Black still remains, as it was for Franklin, far too much of a historical incident in and of itself.

- John Hope Franklin, “The Dilemma of the American Negro Scholar,” in John Hope Franklin, Race and History: Selected Essays, 1938-1988 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989): 303-4. ↩

- Marisa J. Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016). ↩

In early June 2018 i was searching the Alberta Hunter papers at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. The reading room was packed and I had to share a table. I was surprised that I was the only visible person of color using the collections. Just a new experience for me in that space. Great article. I’m going to assign the article and the John Hope Franklin pieces to my class this fall.