A Fuller Black History of the Civil War

This post is part of our online roundtable on Holly A. Pinheiro Jr.’s The Families’ Civil War.

Holly Pinheiro’s The Families’ Civil War is a welcome addition to a growing and nuanced understanding of Black life in the middle of the 19th century. Focused on how Black families were influenced–and, in turn, influenced federal government policies before, during, and after the American Civil War, The Families’ Civil War stands as a reminder of how much war can influence what happens within individual families. This is a fresh perspective on the Civil War era. As Pinheiro points out, “The lived experiences of working-poor northern USCT soldiers’ families, however, have been largely overlooked” (2).

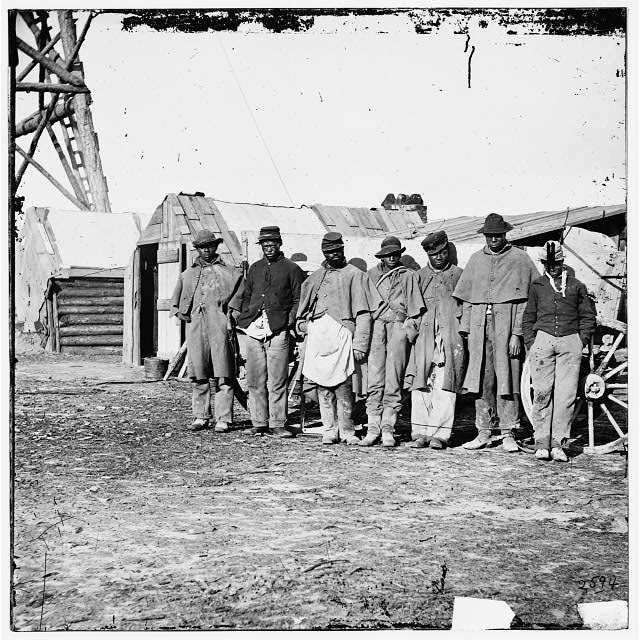

As one who was inspired to study history partly by viewing Glory as a young boy, The Families’ Civil War makes it clear that we should expand who we think about when considering the importance of U.S. Colored Troops to both the history of the American Civil War and the African American experience in American history. For generations, African American soldiers have been key pillars in the teaching and memory of African American history during the Civil War era. But The Families’ Civil War zooms out the focus from the gallant soldiers themselves to consider the plight of their wives, mothers, sons, and daughters. Argues Pinheiro, “Rarely are the experiences of soldiers’ families before, during, and generations after the Civil War pulled together and placed at the center of scholarship” (7). The book is enhanced by focusing on Philadelphia, a critical bastion of Black life in the North before, during, and after the American Civil War.

Reading The Families’ Civil War, one feels compelled to put the book in conversation with other recent works on the Civil War era. The Women’s Fight by Thavolia Glymph, for example, also seeks to go beyond the battlefields of the Civil War to explain what the era was like for different groups of women on the home front. Here, not only does the home front look different, but the war itself takes on a new shape. After all, the struggles of Black families in the North did not begin and end with the Civil War.

The structure of The Families’ Civil War matches Pinheiro’s concern with thinking about a longer history of Black life in 19th-century America. Chapter one, on Black family life in the North before the Civil War, is particularly instructive in considering the circumstances from which many Black soldiers serving in the war came from. It also sets the stage for the rest of the book.

The Families’ Civil War accomplishes the difficult—but imperative—task of humanizing these soldiers by reminding readers where they came from and who they were fighting for.

The remainder of The Families’ Civil War examines the relationship between Black soldiers, their families, and the federal government. This was never an easy relationship. Throughout the book, Pinheiro makes a case for how structural racism in the 19th century time and again harmed the Black soldiers and their families. This is especially clear in his discussion of the significant pay gap between Black soldiers and their white counterparts in the Union armed forces. The title of chapter three, “The Idealism versus the Realism of Military Service,” carefully captures this tension. Again, most Americans today think of the U.S. Colored Troops as unique heroes of the Civil War—quite literally fighting to liberate their families from bondage—but Pinheiro reminds us that we should never lose sight of the sacrifices they had to make that their white counterparts never had to.

Chapters four, five, and six do the yeoman’s work in making clear how the plight of Civil War-era Black families did not end with the war itself. Again, this connects Pinheiro’s work to a broad array of books about the Civil War and Reconstruction periods that argue for a “Greater Reconstruction” outlook on the era. As Pinheiro points out at the start of chapter four, titled “Familial Hardships during the Civil War,” “As the regiments trained and later headed to the frontlines, African American Philadelphian families witnessed the war pull families apart, sometimes in dramatic ways” (73). The racism Black Americans encountered in the North did not end, despite the gallant military service of Black men and the difficult, but essential, work performed by Black women at home and near the front lines.

The Reconstruction era also brought along new challenges for the families of Black soldiers who fought in the war. Securing pensions became a critical problem for them, and this became arguably the greatest symbol of the structural racism these families faced in 19th-century America. “The wives in common-law marriages,” Pinheiro points out, “were automatically deemed ineligible to receive a pension” (84). This was a major problem for Black families, as many of them were common-law marriages. Assumptions about “proper” households plagued Black families and prevented them from receiving the material benefits of marriage and family life. Even though Pinheiro points out earlier in the book how Black families crafted ties of “fictive kin” that went beyond “normal” familial relations, these were often ignored by the white public and the American government.

The Black family, the growth (and retrenchment) of the federal government, and what the Civil War was actually about: all of this and more can be found in The Families’ Civil War. It will certainly upend assumptions about Black life in the North in the 19th century. More importantly, it brings into sharper focus what Black soldiers and their families experienced, and how the debt they are owed by the nation may never be fully repaid. It is a necessary work that stands alongside many other great works on Black military service and life in American history.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Fine work, necessary and much appreciated. It might be useful to encourage readers to visit the Civil War museum in Washington D.C. founded by SNCC veteran Frank Smith, too. And viva that outstanding historian, Prof. Thavolia Glymph!