The Third World Women’s Alliance, Cuba, and the Exchange of Ideas

Since President Obama reestablished diplomatic relations in December 2014 there has been a spike in American travel and interest in Cuba. Increased access has also reinvigorated the focus on black activists—including Robert F. Williams and Assata Shakur—who fled to Cuba to try to escape state-sponsored attempts to exterminate the black liberation movement in the 1960s. These activists have rightly received a lot of attention in the midst of our changing relationship with Cuba. However, Cuba, its leaders, and its revolution have had far more pervasive effects, past and present, on everyday people’s ideas of liberation and equality. The country played a vital role in shaping the ideological and organizational trajectory of many radical grassroots organizations, including the Third World Women’s Alliance (TWWA), a group that championed a globally-conscious, intersectional platform.

The origins of the TWWA lay in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), one of the premier organizations of the black freedom struggle. Throughout the 1960s, SNCC members engaged in unparalleled efforts to increase voter registration, political literacy, and civic engagement, ultimately bolstering black enfranchisement and federal civil rights legislation. Black women in the organization spearheaded these efforts while also claiming a space in anti-war organizations like the National Black Anti-War Anti-Draft Union (NBAWADU), feminist and reproductive rights groups, and SNCC’s International Affairs Commission, an anti-colonial, anti-imperialist research and advocacy arm.

By spring 1969, they formed the Black Women’s Liberation Committee (BWLC) to address these topics from a black women-centered perspective. Activist-intellectuals like Gwendolyn Patton, Frances Beal, and Mae Jackson fostered the group and it quickly outgrew its parent organization. By the end of that year, the BWLC had developed into the Black Women’s Alliance (BWA), a separate, nationalist and Marxist-leaning black women’s organization. By early 1970, BWA members had incorporated other women of color into the group and changed the name to the Third World Women’s Alliance, a shift that reflected their evolving political ideology and membership.

Cuba played a critical role in shaping the TWWA’s ideology and organizational evolution. Beal recalled that many members of the collective “witnessed in Cuba the possibility of a society in the future that was free of racism and the possibility of a society in which women played an active and equal role in society.” Moreover, members like Cheryl Johnson—who would later start the Bay Area chapter of the group—traveled to Cuba and witnessed the post-revolutionary country first-hand. Johnson and others worked with the Venecermos Brigade, a program founded in 1969 through which leftist activists lived and worked in Cuban communities. The TWWA continued this relationship by organizing Los Venceremitos, a similar project that helped young children visit Cuba, publishing news of the Cuban revolution and women’s roles in the country in their newspaper, Triple Jeopardy, and corresponding with families and activists in Havana.

TWWA members credited the country and its people with shaping their political ideology and organizational structure. Their relationships with and experiences in the country sharpened their analysis of imperialism and capitalism and foregrounded the importance of adopting a Third World identification in order to align their group with women of color across the globe. Furthermore, the Cuban revolution was also notable because women participated in great numbers; they mobilized around their gender-specific concerns and articulated a transformative view of women’s emancipation within the Cuban revolution. TWWA members were particularly drawn to this aspect of Cuba’s history and incorporated lessons from it into their worldview.

The Alliance’s ideological platform echoed these influences. In their founding documents, members insisted on the need for an intersectional and international approach to liberation. Or as they put it, “Our purpose is to make a meaningful and lasting contribution to the Third World community by working for the elimination of the oppression and exploitation from which we suffer. We further intend to take an active part in creating a socialist society where we can live as decent human beings, free from the pressures of racism, economic exploitation, and sexual oppression.”

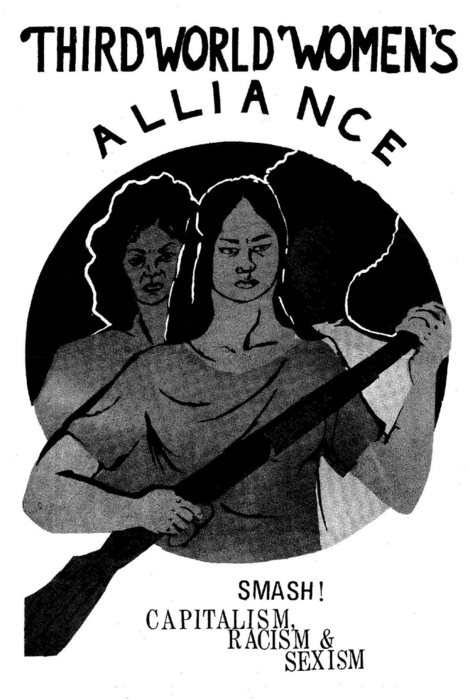

The TWWA also challenged contemporaneous ideas about women’s place in liberation movements. They called for “communal households and the idea of the extended family,” “the sharing of all work by men and women,” “guaranteed full, equal, and non-exploitive employment” for women, an end to “rigid sex roles” and homophobia, and claimed that “third world women have the right and responsibility to bear arms.”1 The group often published these statements alongside images of Cuban women, further promoting the country’s influence within its readership and ranks.

The TWWA and other like-minded groups illustrate the importance of open borders and international exchange. The intersectional framework that the TWWA championed (and that many have adopted today) was as much a product of cross-ethnic, national, and regional dialogue as it was the outcome of women of color’s efforts to theorize their liberation. This has important implications in our nationalist and xenophobic climate today. Far from simply being a threat or a menace to American ideas and idealism, other countries, groups, and peoples offer valuable insight into—and foreground the pitfalls of—reimagining, theorizing, and actualizing liberation. Bans aimed at certain countries are not just designed to minimize security threats or amplify the economy, they are an effort to stymie the flow of ideas that often help the most oppressed theorize liberations and forge alliances. Like Alliance members, we all benefit from material and ideological exchanges with peoples from other cultures, countries, and political climates and we must all remain vigilant about not only who is being banned from some countries, but what ideas the nation-state is invested in suppressing along with them.

- TWWA, “The Third World Women’s Alliance: Our History, Our Ideology, Our Goals,” Box 4, Folder 29, Frances Beal Collection, National Archives for Black Women’s History. ↩