The 1967 Rebellion and Visions of an Independent Black Detroit

In all likelihood, the progressive slogan—“Another city is possible”—grew from the ashes of the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. While many will remember the destruction, the presence of the National Guard, and the many who died during the uprising, it is important to remember that the visions of independent Black urban communities also represent one of the rebellion’s legacies. Black Nationalists in Detroit such as Reverend Albert B. Cleage, Jr. and members of the Malcolm X Society (MXS) devised alternative plans for a Black Detroit and demanded resources from the local corporate and political elite.1

These visions were intellectual and political descendants of Black Nationalist projects stretching back to Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Several other activists emphasized these ideals in the years leading up to the 1967 rebellion. W.E.B. Du Bois outlined his conception of a Black cooperative commonwealth in his 1940 book, Dusk of Dawn: The Autobiography of the Race Concept. Several years later, Detroit labor radical James Boggs argued for the takeover of predominately Black urban spaces in his 1966 essay, “The City is the Black Man’s Land.”

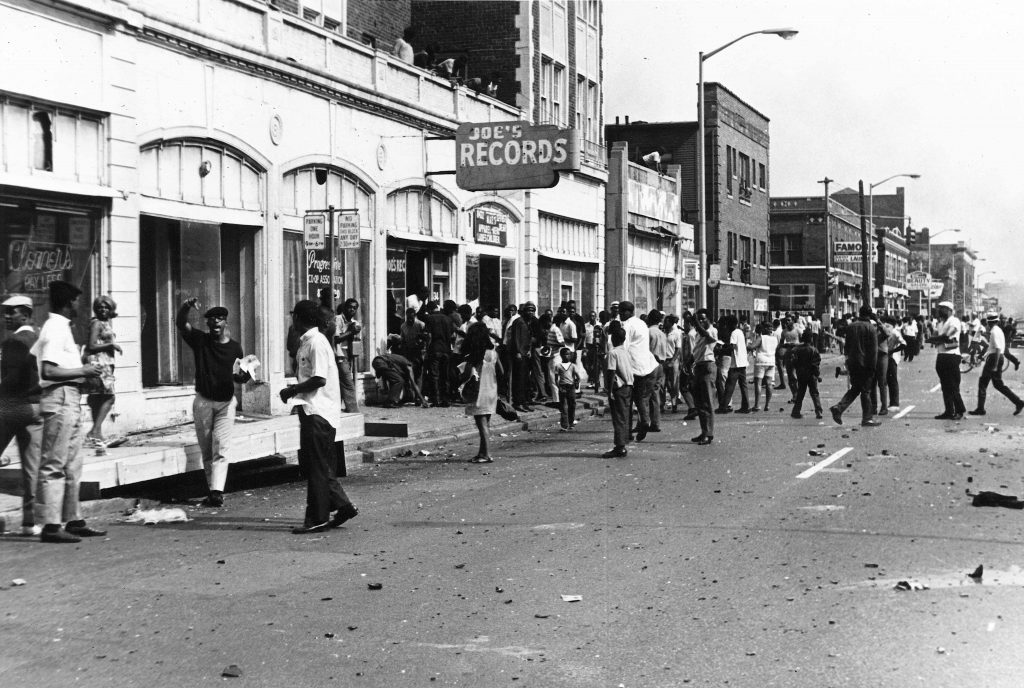

These earlier movements laid the groundwork for the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. Sparked by a police raid of a local bar known as blind pig, the uprising was ultimately the product of more than two decades of racial discrimination in housing, suburbanization, deindustrialization, and racist policing. The insurrection was an uprising from below; many self-reporting participants in a Detroit Urban League survey after the rebellion claimed to be young and unemployed. It was the costliest and deadliest in the nation’s history. The total damage was between $40-45 million. More than 2,000 stores were vandalized, looted, and destroyed. Forty-three Detroiters were left dead while more than 7,000 were arrested. More significantly, however, the uprising reordered city politics.

In the aftermath of the rebellion, Black Power advocates in the city advanced their visions of a new, independent Black Detroit in this unstable political milieu. Members of the Malcolm X Society, a revolutionary nationalist organization established in 1967 by Milton and Richard Henry (who later changed their names to Gaidi Obadele and Imari Obadele), issued a set of demands for Black Detroit. In addition to calling for cooperative housing, they also called for a full employment economy like many progressives before and after them. Members of the Malcolm X Society also demanded the institutionalization of a concept I call Black federalism—a relationship where the state would deal directly with Black-ran communities and cities.2

The Malcolm X Society released their ambitious plan—“New Community: A Proposal for Reconstruction Area #1 in Detroit”—in August 1967. It featured 12,000 homes, youth activity centers, shopping centers, a new school and library, a community and civic center, a community theater and art center, and a business plaza and an industrial park. This plan was also cooperative-based. The MXS plan would be financed by constructing a 7,000 family land cooperative where every person would pay $2 per month. The MXS would also look to the federal government for support. The federal government would serve as secondary investors while black residents would foot most of the bill.

Not all Black Power activists embraced this particular approach. Rev. Cleage, a longtime local activist and Minister at Central United Church of Christ, demanded that white political and economic leaders transfer resources and power to Black-dominated urban spaces.3 In August, Cleage called for Black Detroiters to have total control over businesses and governing institutions, as well as administrative discretion over federal money allocated to Detroit. In an article published the following year, “Transfer of Power,” he advocated for the construction of a Black cooperative economy for Twelfth Street. Cleage’s plan featured the “development of co-op retail stores, co-op buying clubs, co-op light manufacturing, co-op education.” To finance Twelfth Street’s reconstruction, Cleage demanded that white business and political elites cede capital and local institutions of governance to Black Detroiters without any strings attached.4

Cleage helped establish the Citywide Citizens Action Committee (CCAC) and the Federation for Self-Determination (FSD) to initiate a transfer of power. While both organizations drew support from a broad segment of Detroit’s Black population, they encountered an obstacle in the newly formed New Detroit Committee (NDC). The NDC did not acquiesce to Cleage’s demand for a total transfer of power, only a one-time lump sum of $100,000 to run the FSD’s daily operations. New Detroit also forbade the FSD from using the grant for explicit political purposes. Cleage declined and denounced the NDC’s offer as a form of colonialism.

These post-rebellion strategies for Black urban self-determination raise questions about the meanings of Black liberation in a structurally racist and liberal capitalist nation. Were Cleage’s and the MXS’s nationalist urban plans representative of truly liberated Black communities if they sought resources from white-dominated economic institutions? Was Black federalism an adequate strategy to create and maintain “liberated territories?” Cleage’s “transfer of power” strategy contained such tensions. The term, “transfer,” in itself, represented a vexing prospect since white capitalists had to agree to such an arrangement. This outcome seemed very unlikely as a peacetime measure. As Malcolm X asserted to a Detroit audience in his “Message to the Grassroots” in 1963, the “revolution” or the expropriation of property and institutions from capitalists would most likely come from an instance of collective violence.

Like Cleage’s plan, the Malcolm X Society’s desires to rebuild Twelfth Street also force us to think deeply about the process of Black Power. The implementation of Black federalism would have pushed Black and white Americans to rethink the federal government’s relationships to Black-run neighborhoods and cities. If implemented in good faith, such an arrangement would have represented a diversion from white dominance in state and local governments. However, such a concept would have eventually challenged President Richard Nixon’s “new federalism,” which supported less direct federal intervention in affairs in Midwestern and Northeastern cities where Black Americans predominated. Yet, MXS’s plan represented a node in the tradition of economic democracy that extended from the early-twentieth century and through Detroit activists’ and Youngstown steelworkers’ demands for the federal government to provide capital to take over closing and abandoned factories during the late-1970s and early-1980s.

However, would such resources be administered and who would actually control it? Would this new, independent, Black Detroit resemble the cooperative commonwealth outlined by Du Bois? Would it eventually become a Black state administered by a Black capitalist elite? Members of the Malcolm X Society like Richard B. and Milton Henry articulated an anti-capitalist vision whereas Cleage publicly distanced himself from socialism and communism.

We will never fully know the answer to these questions because of the political and structural impediments that plagued Detroit after 1967. Several developments, including the overlapping fiscal, energy, and economic crises, white-flight, the restructuring of federal urban policy, and depopulation due to imprisonment of Black Detroiters, helped to lay the foundation for a forced bankruptcy and displacement of Black political power in 2013.

However, when assessing the legacy of the 1967 Rebellion, we should not always focus on the narratives that center on the bankruptcy, gentrification, and private downtown investments by members of the city’s corporate elite. Thousands of Detroiters rebelled against racist policing, residential segregation, and economic exploitation. This shock from below forced a reordering of the local political and economic elite and thrusted the urban crisis back into the national spotlight. The rebels on Twelfth Street paved a way for activists and organizations such as the Malcolm X Society and Rev. Albert Cleage to envision radically self-sufficient black communities and cities concretely. The 1967 Rebellion, then, teaches us that another city is always possible.

- The Malcolm X Society was the organizational precursor to the Republic of New Afrika. ↩

- Austin McCoy, “No Radical Hangover: Black Power, New Left, and Progressive Politics in the Midwest, 1967-1989 (Ph.D. diss, University of Michigan, 2016), 81. ↩

- Cleage changed the name of the church to the Shrine of the Black Madonna in 1967 to mark its shift towards a Black Christian Nationalist theology. ↩

- Albert Cleage, Jr., “Unite or Perish,” Michigan Chronicle, August 26, 1967; Cleage, “Transfer of Power,” The Center Magazine, Vol. 1, No. 3 (March 1968), 47. ↩