Malcolm X, The Lover

At the risk of seeming ridiculous, let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love. It is impossible to think of a genuine revolutionary lacking this quality. –Ernesto “Che” Guevara in Socialism and Man in Cuba

Malcolm X has been represented by mainstream culture as an emissary of hate and a man who was the very embodiment of radical violence. Both the conservative cultural politics of the Nation of Islam combined with the limitations of mainstream culture in understanding or imagining the complexities of Black love have conspired to create Malcolm X’s legacy as one that largely eschews the question of love, erotic or otherwise.

It is for this reason that when Manning Marable’s long awaited five-hundred ninety-two-page magnum opus on the life of Malcolm X finally appeared in 2011 so much of the discussion of it rotated around the two pages in which Marable alleged that Malcolm X once had a sexual partner of the same gender. Ilyasah Shabazz, the third daughter of Malcolm X, walked off a National Public Radio interview celebrating the release of the book when the host raised it as a question. She noted that “even the FBI files indicated that Malcolm was a saint,” as if eroticism and love could never be congruent with the moral purity of sainthood. Never mind that these same sex encounters were alleged in the context of sex work and occurred in a period in which he would later describe himself as “trapped” and “lost.”

The idea of Malcolm X in relationship to an erotic or affective economy seemed to push beyond the political imagination of some and the boundaries of good taste for many others. Before leaving the radio interview Shabazz said: “I think the things that I take issue with are the fact that he [Marable] said my father engaged in a bisexual relationship, a homo – you know.” Though the homophobia which would label Malcolm X a “homo” for sex work and a fear of the erotic that would deny him sainthood on the same grounds are not the same, they are both related to a basic fear of confronting the complexity of human sexuality and its relationship to the concept of love.

At Malcolm X’s funeral, Ossie Davis famously eulogized him as “our living, Black manhood.” Similarly, poets eulogized in relationship to a hard masculinity. In “Malcolm X,” Gwendolyn Brooks writes: “He had the hawk-man’s eyes./We gasped. We saw the maleness./The maleness raking out and making guttural the air/And pushing us to walls.” Amiri Baraka’s “A Poem for Black Hearts” unintentionally anticipates the discussion of Malcolm X’s sexuality that would come over forty years later when he writes:

For Great Malcolm a prince of the earth, let nothing in us rest until we avenge ourselves for his death, stupid animals that killed him, let us never breathe a pure breath if we fail, and white men call us faggots till the end of the earth.

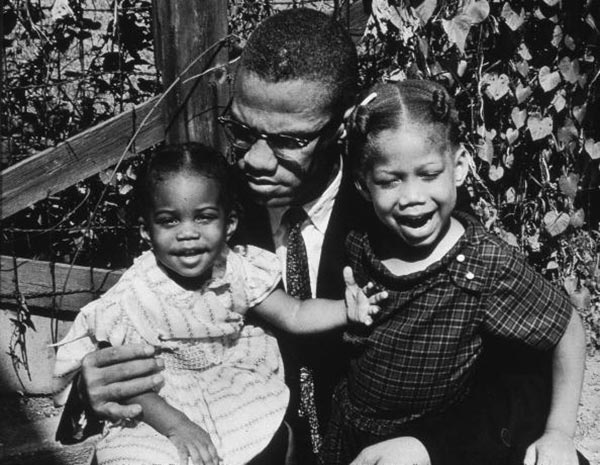

There has been a reluctance and even fear to conceptualize a Malcolm X in a manner that might soften or feminize him in any way. In this conceptualization of love, love is “soft” and unmanly. It is feminine, weak and even counter-revolutionary. This despite the fact that in his private life as the father of six daughters and the husband of Betty Shabazz, who was an equal partner in the creation of his life and legacy, he was surrounded by women and girls. When Malcolm X wrote about the love and devotion that he had for Elijah Muhammad he too cast it in unapologetically hard masculine terms: “My adoration of Mr. Muhammad grew, in the sense of the Latin root word adorare. It means much more than ‘adoration’ or ‘adore.’ It means my worship of him was so awesome that he was the first man whom I ever feared—not fear such as of a man with a gun, but the fear such as one has of the power of the sun”

When Ilyasah Shabazz writes of the few memories that she has of her father, who was murdered when she was only two, he is distinctly gentle and nurturing: “When I heard him coming, I’d go running for the door, and he’d open it and swing me up, up, up, high into the air for a big hug, then catch me under his arm like a sack of potatoes and together we’d the oatmeal cookies Mommy used to make and go watch the evening news. I’m a cookie fanatic to this day.” Malcolm X loved his children with a love built around a profound sense of nurturance. And Ilyasah also reveals that he loved Betty Shabazz with a love that was rich and erotic: “he loved my mother’s smooth, mahogany skin. He called her his Apple Brown Betty and Brown Sugar.”

The desire of mainstream white culture to treat Malcolm X as hateful and harbinger of denaturalized violence has also removed the possibility to read him as an emissary of radical love. The concept of love has been radically simplified in the US cultural imaginary to the point that it is almost exclusively limited to the romantic love between a man and a woman or between a parent and child. It is singular and almost always involves some form of possession. The possession can take the form of a legal contract or obligation—the marriage contract or the legal obligation to provide financially for one’s children—but it can also take the form of a caustic sense of ownership that essentially says: “You will do what I say because I have the right to demand that of you.” This idea of love is reflective not only of heteropatriarchy but it is also demanded by a neoliberal capitalism that has attempted to redefined all social and affective relationships in around the concept of ownership.

Malcolm X dealt in much more nuanced forms of love that both lay outside of legal systems and beyond traditional definitions of love. Assistant Minister Benjamin Karim talked of the great feeling of love and fraternity shared by the ministers in New York Temple #7. This love was founded not on legal obligation or moral suasion of parenthood or marriage but rather on a shared sense of discipline, purpose and mission. This was a love in keeping with the NOI values of fraternity and submission to god. According to Malcolm X’s own words, submission before God was an ultimate act of love and this love was freeing.. In fact, the mosque opened a space for male vulnerability and closeness that would have otherwise been foreclosed by homophobia and fear of the erotic. As Karim wrote, quoting Malcolm X: “Islam gave me wings.”

Perhaps more than any other of Malcolm X’s profound articulations of love was his devotion to uncovering and exploring radical self-love in a people who had experienced literal generations of degradations. Though Malcolm X’s life and legacy is continuously tainted by claims that he promoted violence, we could think of his interest in Black self-defense as a deep investment in Black self-love. When confronted with charges that he and the NOI were “teaching hate,” he brilliantly responded with a set of rhetorical questions that call to a radical self-love.

Who taught you to hate the color of your skin? Who taught you to hate the texture of your hair? Who taught you to hate the shape of your nose and the shape of your lips? Who taught you to hate yourself from the top of your head to the soles of your feet? Who taught you to hate your own kind? Who taught you to hate the race that you belong to so much so that you don’t want to be around each other? You know. Before you come asking Mr. Muhammad does he teach hate, you should ask yourself who taught you to hate being what God made you.

Self-love was a major theme of Malcolm X’s life and work and he made repeated calls to it when he spoke to Black audiences. It is hard to read The Autobiography of Malcolm X—undoubtedly his most impactful work—as anything other than a guide to an evolving self-love. Malcolm X was so invested in the power of self-love that he devoted his most powerful tool to it: his writing. His daughter Attallah Shabazz labels her father “a lover of words” who “very much believed in the power of words to influence and transform lives.” The transformational power of words to redefine lives and create a new sense of selfhood was so strong for Malcolm X that the final wish that he articulates in his autobiography is simply “I would just like to study.”

To understand Malcolm X in all his complexity, we must first acknowledge that his vision for a better world included a world in which we reconceptualize love. His work urges us to move beyond an understanding of love as simple possession and control. It moves us towards a radical centering of masculinity around fraternal love and an imagining of familial love beyond simple ownership or domination but rather in relationship to the supposedly “soft” values of nurturance and partnership. We must also do the work that Malcolm X left undone and contend with the erotic. And most importantly we must understand self-love as a radical act.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Thank you for this, we can always learn more about ourselves and history through our dear leader/ancestor Malcolm X (El Hajj Malik El Shabazz),

There is no better teacher in my opinion.