From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: An Interview with Elizabeth Hinton

This month, I interviewed Professor Elizabeth Kai Hinton on her new book, The War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016). Dr. Hinton is an assistant professor in the Departments of History and African and African American Studies at Harvard University. She spent two years as a Postdoctoral Scholar in the Michigan Society of Fellows and Assistant Professor in the Department of Afroamerican Studies at the University of Michigan before joining the Harvard faculty. A Ford Foundation Fellow, Hinton completed her Ph.D. in United States History from Columbia University in 2013. Her articles and op-eds can be found in the pages of the Journal of American History, the Journal of Urban History, Time, the Los Angeles Times, the Boston Review, and the New York Times.

This month, I interviewed Professor Elizabeth Kai Hinton on her new book, The War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016). Dr. Hinton is an assistant professor in the Departments of History and African and African American Studies at Harvard University. She spent two years as a Postdoctoral Scholar in the Michigan Society of Fellows and Assistant Professor in the Department of Afroamerican Studies at the University of Michigan before joining the Harvard faculty. A Ford Foundation Fellow, Hinton completed her Ph.D. in United States History from Columbia University in 2013. Her articles and op-eds can be found in the pages of the Journal of American History, the Journal of Urban History, Time, the Los Angeles Times, the Boston Review, and the New York Times.

***

Garrett Felber: Your book very successfully blends together methodologies from significant and recent works on crime policy and rise of mass incarceration: the intellectual history of Khalil Muhammad’s The Condemnation of Blackness and the policy history of Naomi Murakawa’s The First Civil Right. Could you talk a bit about the research for this project? What were your principal archives? What obstacles did you face? And which voices do you feel are still missing within the larger conversations happening in political science and history surrounding these issues?

Garrett Felber: Your book very successfully blends together methodologies from significant and recent works on crime policy and rise of mass incarceration: the intellectual history of Khalil Muhammad’s The Condemnation of Blackness and the policy history of Naomi Murakawa’s The First Civil Right. Could you talk a bit about the research for this project? What were your principal archives? What obstacles did you face? And which voices do you feel are still missing within the larger conversations happening in political science and history surrounding these issues?

Elizabeth Hinton: The archival research for this book was extensive. I mostly worked with the White House Central Files of the Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, Carter, and Reagan administrations, examining every document I could get my hands on that contained a shred of information related to issues of crime, punishment, and black Americans. I also visited the Department of Justice collections at the National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, Maryland and conducted a few interviews with former Justice Department officials.

The process of declassifying documents through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests proved to be one of the biggest obstacles in researching this topic. In many ways I’m lucky I could get my hands on anything since “information compiled for law enforcement purposes” is one of the exemptions for FOIA release. I had to make a lot of requests to declassify documents, particularly at the Reagan library, a number of which are still pending. I’m eager to see what other researchers discover once these documents are made available.

Although many files remain classified, I consulted tens of thousands of pages of internal memoranda, reports, meeting notes, and correspondence in the presidential archives. As the national law enforcement bureaucracy grew during the 25-year period at the center of my study so did the paper trail. One of the most curious and frustrating things about the research process for this book is that a good chunk of the records of the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA)—the grant-making arm of the Department of Justice (DOJ) that the Johnson administration created to fight the War on Crime—are missing. These files essentially vanished from the DOJ archives from 1971 through 1976. So it’s harder to keep track of what’s going on from the DOJ side during the Nixon/Ford era. When you press the DOJ specialists at the National Archives about the gap in record-keeping, they tend not to have ever heard of the LEAA. This is alarming, especially given the fact that the LEAA disbursed $10 billion in taxpayer dollar ($25 billion in today’s dollars) to improve policing, court, and prison systems at all levels of government during its relatively short life span. The agency disbanded during Ronald Reagan’s first year in office, but the nation is still haunted by its legacy.

So there are some critical gaps in the federal sources, but building off of the work of the scholars you mentioned, and many others—Vesla Weaver most directly, in that she was the first contemporary scholar to really take on the strange beast that was the LEAA—I think the book helps to open up new questions and understandings of the development of the modern carceral state. Still, the voices that are largely absent from the conversation and that need to be front and center are those Americans who experienced the rise of urban police forces and mass incarceration firsthand: the human causalities of the War on Crime. We often talk about these issues in a top-down way, and the solutions are to be discovered among the people themselves.

Felber: We constantly see examples in your book where policymakers respond to a crime commission by enacting (often short-range) punitive strategies and recommendations while neglecting (often long-term) social welfare reforms. In the mid-1970s, Senator Edward Kennedy wrote that even if “social policies we initiate in the 1970s will reduce the crime rate in the 1980s . . . that is too long to wait.”

I wondered if you’d discuss some of the reasons for policymakers’ repeated choice of immediate crime reform alongside deferred investment in schools, jobs, and housing. Is this a product of four-year election cycles? Are there other reasons?

Hinton: I offer a more nuanced examination of the dynamic you’re getting at in the book, but the short answer is racism. Consistently, and across political and ideological lines, policymakers have been unwilling to disrupt the racial and class hierarchies that have defined the United States historically. The view of black poverty as the product of black cultural pathology—the guiding principle of domestic urban policy beginning in the 1960s—limited the War on Poverty’s possibilities. And throughout the 1970s, even when community-based law enforcement programs and alternatives to formal incarceration proved to not only be cost-effective, but to also respond to the problem of crime far more effectively than the dominant strategies policymakers embraced, officials cut these initiatives short or installed them in rural and suburban communities.

The Kennedy quote is telling: policymakers recognized the socioeconomic root causes of crime—namely, unemployment and failing public schools in low-income urban communities—but they decided to manage the symptoms of those problems as they manifested in crime and violence. Short-term, knee-jerk reactions always won out over long-term solutions to social harm that require a lot of patience and commitment. There is a real resistance on the part of elites to truly empower communities to solve their own problems on their own terms. Until lawmakers are willing to cede power, the same failed programs will continue to erode our social life and democracy.

Felber: As the carceral state expands in your narrative, there are more and more interactions between people and the police, probation officers, and other state actors. As you demonstrate, this entangles more citizens in the carceral system at a younger age. Are there ways in which this contact with the state also politicized people? I am thinking here of Rhonda Williams’ work on public housing, where she notes that low-income black women often received their political education through encounters with the welfare system.

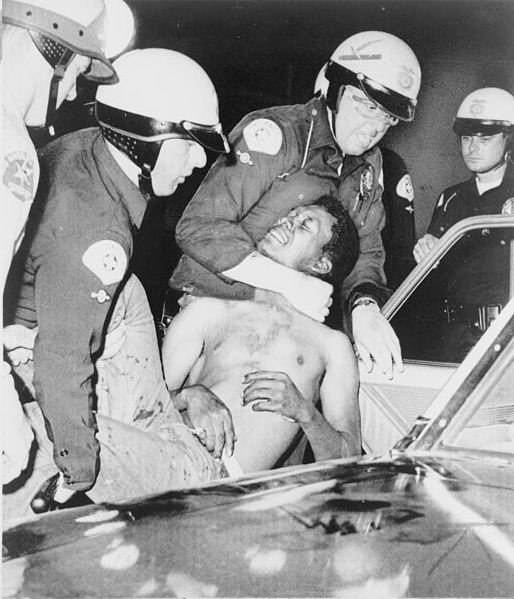

Hinton: Routine, aggressive, and all-too-often lethal police encounters between black Americans and law enforcement authorities have been a source of protest and resistance historically. Beginning in the mid-1960s this erupted into full scale rebellion, and the revolts and protests continued through the 1970s. Since the problems have remained, and since awareness of racial profiling and police brutality has grown in recent years, people are rising up against racist policing practices across the country from Ferguson to Baton Rouge. So yes, living under omnipresent surveillance and patrol politicizes targeted groups. It also makes citizens of color less trustful of state institutions and ambivalent about U.S. democracy. Amy E. Lerner and Vesla M. Weaver’s Arresting Citizenship: The Democratic Consequences of American Crime Control presents one of the most convincing examinations of this dynamic.

In addition to politicizing communities and compromising the state’s legitimacy, contact with law enforcement authorities can also have the adverse effect. When ordinary childhood activity is treated by authorities as delinquent, and the spaces in which low-income children of color interact are systematically criminalized, “the person becomes the thing he is described as being,” as the sociologist Frank Tannenbaum wrote in 1953’s Crime and the Community. In my Journal of Urban History article, “Creating Crime,” I wrote about the experience of Tim K, who came into contact with a police officer at the age of eight. One Saturday afternoon in 1974, a police officer spotted Tim playing on the swing set of his elementary school in South Central, Los Angeles and apprehended him for trespassing. Sitting in the back of the police car, Tim told me his first thought was “if that’s the way you’re going to treat me for no reason, I’ll have a reason next time.” Tim went on to spend much of his childhood and teenage years going in and out of Juvenile Hall and the California Youth Authority before “graduating” to prison. As one example of many, Tim’s life story underscores that preemptive contact with police and incarceration do not deter crime. Instead, Tim’s story illuminates that violence begets violence. Placing a black child in handcuffs and arresting him for something that his white counterpart would almost certainly never be charged with is a violent act.

Felber: It seems that there are two interrelated, yet distinct, themes in the book: one is the merging of social welfare programs with the carceral state; the other is the supplanting of the War on Poverty with the War on Crime. And of course, we have moments where the two seem utterly overlaid such as when the Crime Commission claimed that “Warring on poverty . . . is warring on crime.” Do you see this as a story of one replacing the other, their increased imbrication, or both?

Hinton: The merger of antipoverty and crime control programs is a process that unfolds over the course of the 1960s, beginning with John F. Kennedy’s antidelinquency demonstration programs that established the federal government’s intervention in targeting black urban communities. When Johnson signed the first major piece of national crime control legislation into law—the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968—and the first federal law enforcement grants hit the ground, this merger transitioned into something else entirely. Richard Nixon seized upon the darkest elements of the Great Society while disinvesting from social welfare programs when he took office. Over the course of the 1970s, the LEAA administered programs that had been squarely under the purview of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare and the Office of Economic Opportunity. Meanwhile, state and local authorities were increasingly forced to turn to the punitive arm of the state to run after school, counseling, and job training programs. By the time we get to the Carter Administration, crime was seen by policymakers, officials, and the social scientists they consulted as the root cause of the “urban crisis,” rather than socioeconomic conditions. Urban policy and law enforcement programs become one and the same. For example, the Department of Housing and Urban Development started diverted funding to security and surveillance concerns, rather than the rodent control or the playgrounds or the green spaces that resident themselves wanted.

Questions of intentionality underscore the dynamic between this merger of social programs and the supplanting of one domestic social war for another. I believe that Johnson hoped his Great Society programs would, in his words, “strike down” both poverty and crime, even though the set of racist assumptions that informed the policies of his administration made this goal an impossible one to achieve. (How can you end poverty without job creation and redistributive programs?) But, as I see it, Nixon and subsequent policymakers developed crime control programs as a means to manage, rather than ameliorate, the material consequences of historical racism and socioeconomic isolation. By the 1980s, as crime control and incarceration became the most widely implemented social program in America, police officers emerged as the primary public institution in many low-income black and brown communities.

Felber: No one book, can (or should) purport to cover everything. What other books or articles would you recommend that people read alongside yours to understand the full scope of the rise of mass incarceration and the carceral state?

Hinton: The regime of punishment that emerged in the post-Emancipation south is a crucial yet underexamined chapter in American history, one that is necessary for us to fully understand anything about race and criminalization today. The deep racial dimensions of contemporary mass incarceration become even more clear when issues of crime, punishment, and social control are considered within this longer historical trajectory. I’ve found David Oshinsky, Mary Ellen Curtin, and Douglas Blackmon’s work eye-opening for students. Talitha LeFlouria’s Chained in Silence: Black Women and Convict Labor in the New South and Sarah Haley’s No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity are powerful new additions to the field. But if I could only choose only one book for an interested reader to engage, it would be Khalil Muhammad’s The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America. I think most other historians would agree. You can’t tell the story of the rise of mass incarceration without seriously taking into account the role of social science research in creating the myth of black criminality.

If readers want a more comprehensive study of the problem, Marie Gottschalk’s Caught and the National Academy of Sciences 2014 Report The Growth of Mass Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences are solid starting points. Kali Gross’s Colored Amazons: Crime, Violence, and Black Women in the City of Brotherly Love, 1880–1910 and Dan Berger’s Captive Nation: Black Prison Organizing in the Civil Rights Era are indispensable. And even though it won’t be released until later this month, I’m anticipating that Heather Thompson’s Blood in the Water: The Attica Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy will be an instant classic.

Perhaps most importantly, we need to familiarize ourselves with the voices and experiences of people who have lived in the belly of the beast. There are tons of prison narratives and memoirs out there, but I frequently turn to the writings of George Jackson and Angela Davis. My students appreciate Davis’s reader, If They Come in The Morning: Voices of Resistance and the harrowing account of urban violence and prison warfare that Colton Simpson offers us in Inside the Crips: Life Inside L.A.’s Most Notorious Gang. Most recently, we have Shaka Senghor’s compelling Writing My Wrongs: Life, Death, and Redemption in an American Prison, but there are plenty of other inspiring works out there. Buy a copy so these books will continue to be released by major publishing houses.

Felber: Where do we go from here?

Hinton: The tragedies we have witnessed over the past several years, and especially this summer, are forcing new national conversations. It’s becoming clear to increasing numbers of citizens that we are at a crossroads. Some white Americans are beginning to come to terms with their own privilege and historical racism, and this is promising, but these conversations need to start in our elementary schools and they need to continue at the national level.

I’m rolling my eyes at myself here because “national conversation” only takes us so far. We must go vote for the candidates that best represent our values in November! We must keep pressuring policymakers and the public to address issues of poverty, inequality, and criminalization by spreading awareness through political education and protest. And we must reckon with and acknowledge the worst and most coercive aspects of our past in order to begin to envision a more equitable and just future.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Thank you for the work done and this article. It might just as easily been titled America’s Shame. Can’t say I enjoyed reading it, but I’ll definitely purchase the book.