False Choices: Identity Politics and Lessons from the Left

Recently my academic-laden social media feeds have been filling up with denouncements of identity politics, or occasionally denouncements of those denouncements. Many of these are responses to Mark Lilla’s opinion piece in the New York Times blaming Clinton’s loss on identity politics. In these debates class and identity are at times posed as opposites, one drawing energy away from the other. One doesn’t have to be trained in intersectional feminism to view this as a false choice, although that would be right in my case. One only has to look at historical examples.

I have been researching and writing about civil rights unionism in the 1930s, a topic that was most extensively explored in the dry and dusty labor histories of the 1970s and 1980s. This movement, particularly its southern incarnation, brought together the socialist left, feminists, black and white workers, and New Deal ideologues. The Highlander Folk School and Southern Tenant Sharecroppers’ Union (STFU) are perhaps the best example of civil rights unionism. Like the “social unionism” that defined progressive-era workers’ education programs, civil rights unionism sought to create a new social order, rather than implement incremental reforms. The movement was interracial and included the active participation of whole families, including women. Most importantly, belying the notion that identity and class are antithetical, it blended class politics with the politics of race and gender equality.

Many of the leading activists of the civil rights movement, like Ella Baker and Pauli Murray, emerged from this vital interracial movement. In the 1930s and 1940s, they promoted cooperatives as socialist alternatives to capitalism and helped pioneer nonviolent direct action. Civil rights unionism also directly influenced New Deal liberals, who borrowed their strategies when crafting programs like the Farm Security Administration’s cooperative farms. And religion was a vital part of civil rights unionism, particularly the prophetic faith of white pacifist A. J. Muste and black theologian Howard Thurman, analyzed in Albert Raboteau’s recent book, American Prophets.

Their activism was as comprehensive as their goals, going well beyond the picket line. For example, they skillfully deployed culture, from the repurposing of “We Shall Overcome” by Highlander to the labor theater groups that activists dispatched to the scenes of strikes. As Doug Rossinow noted in a recent article this movement also linked progressives and liberals in generative ways. “From the 1910s through the 1940s,” states Rossinow, “liberal Democrats sometimes welcomed political support from socialists and other leftists.” Most importantly, these activists and politicians challenged white working-class racism directly, rather than separating class politics from the damage that segregation and racial violence wrought.

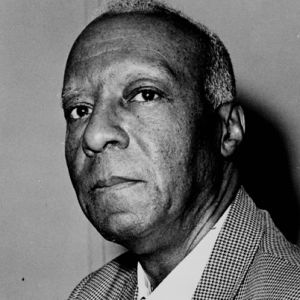

Although civil rights unionism faltered with the advent of the cold war, which marginalized socialists and other radicals, its legacy for the long civil rights movement was significant. The nonviolent direct action tactics honed during this period, particularly by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), were later deployed in Montgomery and countless other cities. And as William P. Jones has argued in The March on Washington: Jobs, Freedom, and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights, labor leaders such as A. Philip Randolph profoundly shaped the economic message of the civil rights movement, which combined jobs and freedom.

This history reveals that resistance movements are strongest when activists do not make false choices between class and race, or other forms of identity. And electoral politics are most progressive when liberals listen and learn from their radical allies.

Victoria W. Wolcott is a professor of history at the University at Buffalo, State University of New York, where she teaches urban, African American, and women’s history. She is the author of Remaking Respectability: African American Women in Interwar Detroit (2001) and Race, Riots, and Roller Coasters: The Struggle over Segregated Recreation in America (2012). Her current research focuses on the emergence of experimental interracial communities in mid-twentieth-century America and their influence on the long civil rights movement. Follow her on Twitter @VWidgeon.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

As a white male, philosopher, and mathematician, I fail to understand how identity politics if “fine for thee, but not for me”. It is 100% disingenuous to say that everyone but white males are accepted in the “identity politics” group. Everyone else gets full support for voting for someone who looks like them, EXCEPT white males, who are vilified for doing so.