Braveheart for Black People: A Review of Birth of a Nation

I was invited to see Nate Parker’s dramatic retelling of Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion right before it opened to the general public. Three quarters of the way into what is arguably one of the best movies on slavery made in recent years for a popular audience, I was suddenly unable to get one phrase out of my mind: Braveheart for Black people. As this sentence prattled its way between my ears, I was overcome with a sudden sense of emptiness. The intrigue of a movie that takes seriously the role of black religion and that wonders aloud about what it means to be a charismatic black leader suddenly was trapped in the clichés of Hollywood.

Nate Parker created an excellent cinematic depiction of the origins of black charismatic leadership. The character of Nat Turner captures the flaws in both of the choices, appeasement, or confrontation, available to African American leaders fighting to protect their people under a hostile regime. It also does a superb job of describing how the gestures of appeasement and confrontation were not merely political responses but were authorized by the deep religious commitment of Nat Turner and his flock. For far too long, thinkers, especially those on the left, have tried to imagine a politics that could divorce religious experience from rational interests. In demolishing this division, Birth of a Nation especially shines. The tipping point for Nat Turner is not the worldly concerns of his people, but the question of whether his master may forbid him from performing his religious rites, in this case the baptism of a white man. In this way, Nat Turner’s righteous anger about the condition of his people mixed with his religious obligation to recognize every man as equal in the eyes of his Creator.

Nate Parker as Nat Turner executes a stunning scene in which he and the white preacher go back and forth quoting passages of the Bible that authorize, alternatively, liberation or submission; but then what was a revelatory movie suddenly gets trapped in the formulas of Hollywood. The challenge was formidable: how does a director depict truly revolutionary violence on screen? However, by wallowing in a sullen and largely silent phantasmal scene of killing, Nate Parker is not up to the challenge. We get a hero whose power originates in his ability to craft words, who suddenly becomes silent during the last portion of the film, right as his righteous anger boils over. The killing is personalized. Nat Turner speaks primarily to authorize the personal nature of the violence and cruelties such as beheading. Parker fails to narrate the larger purpose of the killing, whether it was political, religious, or otherwise. Finally in the recreation of a William Wallace-like execution from Braveheart, the director loses his last chance to have Nat Turner’s character speak, tersely grunting “I am ready,” which lacks even the amorphous possibilities of Wallace’s chant, “Freedom.”

In my eyes, it is at this moment that Nat Turner once again became Nate Parker. What Nate Parker believes to be transgressive, perhaps even liberatory violence, becomes merely the wish fulfillment of a black college athlete on a predominately white team who is forced to watch movies with Scottish-American, Irish-American or Italian-American heroes slaughtering their oppressors before his team hits the playing field. These movies clearly riled Parker and his teammates up about the righteousness of their inevitable victory. The movie he directed reads as Parker dreaming of his own hyphenated hero, one who would emulate those around him, speaking to his own peculiar gods in justification of his actions. With an ending scene seemingly straight out of Glory, African Americans proudly serving in the Union army, the most integrated of American institutions, the viewer is left to marvel at the place that African Americans have built for themselves from their humble origins in America’s kingdom. It is as if Nate Parker, whatever his intentions, wants to re-remember the meaning of American slavery as a chance for Black Americans to say that we too could seize and slaughter, that we too could be just like those around us. That we too could be the rightful heirs to this stolen land.

Perhaps Nate Parker’s vision of Nate Turner as a pivot in the African American freedom struggle is correct. In 1967, Harold Cruse wrote about systemic hindrances of the Negro intellectual:

…America, which idealizes the rights of the individual above everything else, is in reality, a nation dominated by the social power of groups, classes, in-groups and cliques—both ethnic and religious.

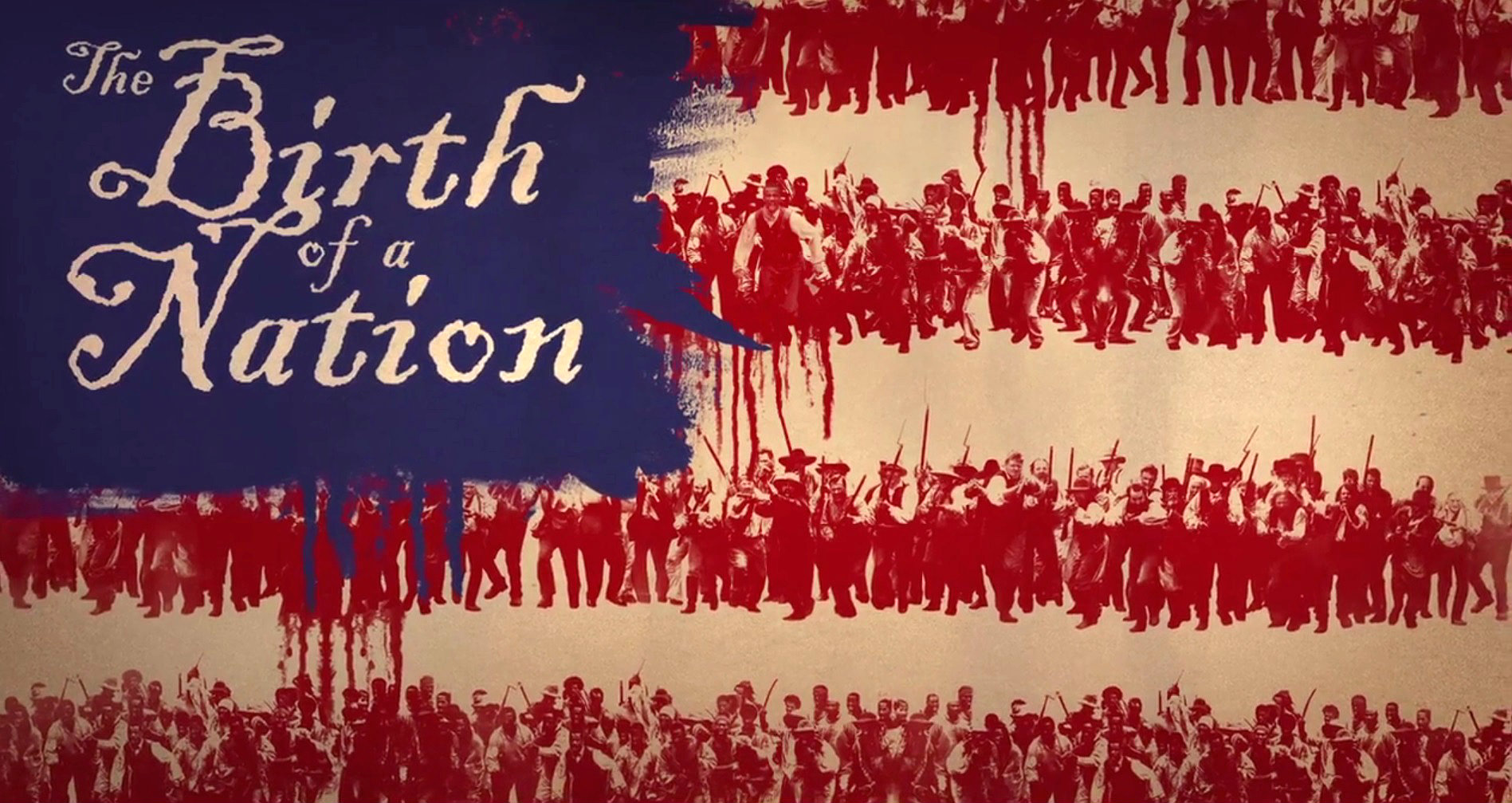

Named after the other 1915 movie of the same title, which did so much to define white racial grievance, Nate Parker’s Birth of a Nation is clear in its mission to remedy the failings of African Americans to grab hold of their own racial grievances or to demand remedy in full. However, in sticking to racial politics without making reference to either the particularity of the Black experience or its potentially universal message, I wonder if Nate Parker forecloses the possibility of Black Americans as a revolutionary force. In the process, does he cheapen the message of Martin Luther King in “Why I Oppose the War in Vietnam”? Does Parker surrender the argument that the salvation of Africans in the Americas also means the salvation of all of humankind from the materialism of capitalism, a materialism that reached its pinnacle in the New World?

Perhaps seeing in Nat Turner a revolutionary is mere wishful thinking on my part. As the classicist Mary Beard reminds us, Spartacus, who led a slave revolt in the 70s BC, has become the literary archetype of slave resistance, and has been depicted as everything from a working class hero of the proletariat to a man merely trying to make it home to his family. While Stanley Kubrick’s version of Spartacus is undoubtedly historically inaccurate, Kubrick inserts a politics where his main character debates the very meaning of freedom, a debate that is sorely missing from Nate Parker’s movie.

Alden Young is an assistant professor of African History and the Director of the Program in Africana Studies at Drexel University. He offers courses in African History, economic history and the history of Arab and African interactions. His book, Transforming Sudan: Decolonisation, State-Formation and Economic Development, is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press. Follow him on Twitter @Alden_Young

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

I felt like the movie did not celebrate his death enough ,it was like e everybody was just waiting on him to die after the revolt.