Antiracism and the Cuban Revolution: An Interview with Devyn Spence Benson

This month, I interviewed historian Devyn Spence Benson about her forthcoming book, Antiracism in Cuba: The Unfinished Revolution (University of North Carolina Press, April 2016). Based on extensive archival research in Cuba and the United States as well as interviews with Afro-Cuban activists, Antiracism in Cuba explores public debates about race and racism in Cuba following the 1959 revolution. Benson reveals how the state’s ambitious campaign to eliminate racial discrimination was ultimately undermined by racist caricatures of Afro-Cubans in the media, the dismantling of independent black and mulato institutions, the underrepresentation of Afro-Cubans in highest ranks of the government, and the pervasive ideology of raceless nationalism.

Dr. Devyn Spence Benson is Assistant Professor of History and African and African American Studies at Louisiana State University (LSU). She received her Ph.D. in Latin American History from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her work examines the history of Modern Latin America and the Caribbean with a particular focus on black activism in Cuba. She has received fellowships from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the Oakley Center for the Humanities and Social Sciences at Williams College, and the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research at Harvard University. Benson’s recent publications have appeared in the Hispanic American Historical Review, the Journal of Transnational American Studies, and PALARA: Publication of the Afro-Latin/American Research Association. She currently serves as the faculty director for LSU’s Honors College study abroad program in Cuba.

Dr. Devyn Spence Benson is Assistant Professor of History and African and African American Studies at Louisiana State University (LSU). She received her Ph.D. in Latin American History from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her work examines the history of Modern Latin America and the Caribbean with a particular focus on black activism in Cuba. She has received fellowships from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the Oakley Center for the Humanities and Social Sciences at Williams College, and the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research at Harvard University. Benson’s recent publications have appeared in the Hispanic American Historical Review, the Journal of Transnational American Studies, and PALARA: Publication of the Afro-Latin/American Research Association. She currently serves as the faculty director for LSU’s Honors College study abroad program in Cuba.

***

Antiracism in Cuba examines public debates about race, racism, and blackness in Cuba between 1959 and 1961. Why did you elect to focus on the first three years of the revolution? What is significant about that particular historical moment?

Benson: When I think about the years between 1959 and 1961 in Cuba, one of the things that immediately comes to mind is that so much was unknown. In 1959, we did not know that Cuba and the United States would break diplomatic relations. We did not know that Fidel Castro was going to be in power for over 50 years. We had no idea that Cuba was going to become a socialist country and aligned with the Soviet Bloc. So many of the political debates and the events that laid the groundwork for those major things to happen occurred in that three-year period. So it was fundamentally a moment when the course of the Revolution was up for grabs. Conversations about race, integration, and nationalism played such a big role in that. For me, it became really important to examine how we look at these three years in order to understand how the Revolution became consolidated.

The second reason that it became really important for me to study the period between 1959 and 1961 is that I wanted to debunk the idea that revolutionary racial politics—the ones that we see throughout the latter part of the twentieth century—emerged because of the government’s turn to socialism. I actually find that revolutionary racial policies have more to do with over 100 years of Cuban racial history, and the histories of people of African descent in Cuba, than they have anything to do with how socialists or communists approach race. So it’s misleading to say that “Castro and the other Cuban leaders don’t talk about race because they’re socialists or they’re communists.” In reality, the reasons that they made the choices that they did in terms of racial discourses are based primarily on Cuba’s distinctive racial history, and we can only see that if we explore how their stance on race and racism consolidates before they ever officially became socialists in 1961.

In March 1959, less than three months after the rebels toppled Fulgencio Batista’s regime, Fidel Castro announced a new state-sponsored campaign to eliminate racial discrimination. As you discuss, few onlookers would have predicted that the new government would launch a major antiracist initiative given that the leaders of the 26th of July Movement (M 26-7) had been relatively silent about the plight of Cubans of African descent before taking power in 1959. What spurred Castro and the revolutionary government to address the problem of racial inequality?

Benson: As I discuss in the book, one of the reasons that people would not have predicted the antiracism campaign is because ending racial discrimination was not an explicit part of the M 26-7 platform. During the fight against Batista, M 26-7 leaders used quotations from nineteenth-century independence leaders like José Martí to articulate their platform and they spoke generally about equality for all. The M 26-7 platform from the 1950s talked about ending unemployment, reforming education and healthcare, and fighting against general social ills, rather than anything specific about race or racism.

When revolutionary leaders announced that they were going to launch a “battle against racial discrimination” in March 1959, I think they did so for a number of reasons. The first one is that Afro-Cuban activists were pushing them to do so. As historians Melina Pappademos and Frank Guridy have both shown, black and mulato activists throughout the twentieth century had made political alliances with previous administrations and exchanged votes for resources. So it makes sense that when there was a new government in power in 1959, Afro-Cubans continued their well-established pattern of working with government leaders to garner access to jobs, to political opportunities, and to other resources the state could provide. Thus, many Afro-Cuban activists viewed the change in government as a moment to push for their agenda. The new administration faced demands by black social club leaders, journalists, communists, and labor leaders to eliminate racial discrimination. As a result, one of the reasons that M 26-7 had to launch a campaign against racial discrimination was because they were being pushed to do so publicly.

Second, they also needed to consolidate the Revolution in the aftermath of the long civil war. There had been almost a decade of armed fighting in Cuba and they needed to move quickly to get people behind the new revolutionary government. In order to do that, they tried to consolidate the new government around the popular classes, including working-class people of color.

How did Afro-Cuban activists respond to the government’s anti-discrimination campaign?

Benson: Afro-Cubans responded in a variety of ways. One way is that obviously many people supported it. When Castro made the announcement and said, “We’re going to eliminate racial discrimination, and this will be one of the battles of the Revolution,” many blacks and mulatos applauded. They were incredibly excited that revolutionary leaders were condemning racism. There were also activists who negotiated with the state and tried to push for more. In the book, I explore how Afro-Cuban activists used the exact same rhetoric that the government employed in the campaign against racial discrimination. However, they turn the rhetoric on itself in order to pressure the government to provide more rights and resources to Afro-Cubans. Once the revolutionary government began using antiracist rhetoric and linked it to the Revolution, some Afro-Cubans responded with even more robust demands.

Finally, a third group of Afro-Cubans were really hesitant. They appreciated that the government was willing to address racial discrimination, but they wanted to lead their own movement. They wanted to be in charge of antiracist activism on the island and they wanted to run the campaign from autonomous black social clubs and organizations. This third group faced a great deal of challenges, because there wasn’t much space for independent black political mobilizations in Cuba in 1959 or 1960.

Discussions about race relations in Cuba, as you argue in Chapters Three and Four of the book, took place before a “transnational audience” and unfolded in the context of the Cold War. How did government officials attempt to shape international perceptions of race relations in Cuba? What role did Afro-Cuban activists play in the state’s efforts to build alliances with black communities in the United States and elsewhere?

Benson: One of the things that is particularly interesting about studying this period is that you’ve got the significant changes that are occurring in terms of domestic race relations in Cuba. At the same time, it’s the 1960s. There are so many things that are going on internationally—the Civil Rights Movement in the United States and anticolonial struggles in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean—that you really get a sense that Cuban leaders were aware that they were on the cutting edge of conversations about race relations globally.

In terms of a transnational audience, the first time that the Cuban delegation goes to the United Nations meeting after Fidel Castro and the revolutionary government comes to power is in September 1960. Castro leads the delegation that travels to the United States and he’s planning to discuss what the Revolution is doing and why it is so important to Cubans and to people around the world. However, the U.S. government bans the Cuban delegation from leaving Manhattan and puts an area restriction on how far they can travel beyond their hotel. Of course, that is not the way that revolutionary leaders expect to be treated.

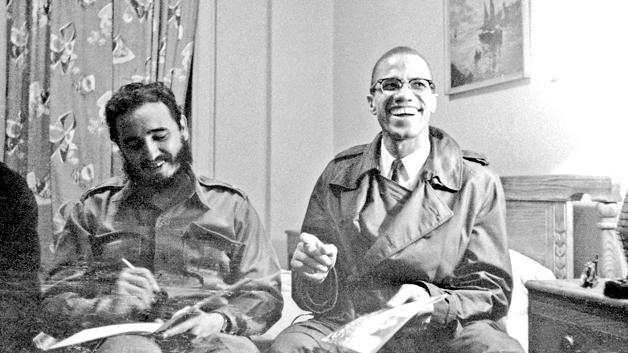

Angered by the restrictions, Castro leaves his Manhattan hotel, drives down to the UN, and says that he’s going to sleep on the front steps of the UN building, if necessary, to protest the restrictions. But at the same moment, there were people in the Cuban delegation who had been in conversation with African American leaders, and they suggested that the Cuban delegation should relocate to Harlem. They end up moving the entire 80-person Cuban delegation to stay at the Hotel Theresa in Harlem. The Hotel Theresa, which had this long history of being a place where famous African Americans like Joe Louis and Josephine Baker stayed while visiting New York, now becomes the place where the Cuban head of state and the entire Cuban delegation to the UN are staying. While the Cuban delegation is in Harlem, they are met by crowds of cheering African Americans. People were really excited that a visiting head of state was willing to stay in a black-owned hotel in Harlem. Furthermore, while they’re at the Hotel Theresa, Castro has meetings with Malcolm X and with African leaders. Back in Cuba, the newspapers publish articles declaring Cubans’ solidarity with the African American freedom struggle and use terminology like “our black brothers.” The Cuban government recognized that racial discrimination and racial violence were vulnerabilities for the United States.

Now, the other fascinating part of this particular story is that the 80-person Cuban delegation that stays at the Hotel Theresa is all white. So they’re in Harlem meeting with African American activists discussing racism in the United States and they have to send a telegram requesting that Juan Almeida, the leading Afro-Cuban revolutionary leader, come to Harlem to join the delegation! You know, sometimes you find a smoking gun in the archives and it’s awesome. And for me, it was when I found the telegram about Juan Almeida. The delegation wanted Almeida to come to Harlem, so that they could show that there were high-ranking black and brown leaders in Cuba. In the book, I argue that this is one of those moments when the Cuban government is actively working to shape international perceptions. On the one hand, they know that it’s a positive thing to move to Harlem. But they also need to be able to demonstrate that they have an integrated revolutionary leadership, and they did that very purposefully while in Harlem.

Antiracism in Cuba includes over a dozen reproductions of political cartoons, including the arresting image of a Ku Klux Klan member being strangled by Fidel Castro’s beard that appears on the front cover. How did visual images such as political cartoons and advertisements shape public discussions about racism and antiracism in Cuba between 1959 and 1961?

From El Mundo (September 23, 1960)

Benson: The visual images really give us a glimpse into the contradictions in the government’s campaign. On one hand, you have leaders who are making antiracist declarations. They’re publicly announcing their solidarity with Afro-Cubans and African Americans and also with global antiracist and anti-colonial struggles of the 1960s. But then at the same time, you have revolutionary cartoonists drawing Afro-Cubans in the same stereotypical way that they had in the pre-revolutionary period. You see the same exaggerated features, infantile caricatures, and minstrel-like comical sketches of black people. As I discuss in my book, many of these revolutionary cartoonists had fought in the Sierra Maestra and were part of the 26th of July Movement. They were not just peons submitting drawings to the newspaper; rather, many of them were actually close to the revolutionary leadership.

When I discuss the political cartoons, one of the things that I like to say is that they’re giving you new ideas, but they’re doing so with old packaging. These political cartoons illustrate the contradictions of the state’s antiracist rhetoric and reveal the part of it that devalues blackness, black history, and black culture, even as they claim to want to be inclusive. The book seeks to tease out that tension.

Finally, I want to say a bit about the images on the book’s cover. In your question, you mention the arresting image of Castro strangling the Klansman. But what’s most fascinating for me about that cartoon is the image right next to it, which is also on the book’s cover and is from the same page in the newspaper. Right next to the cartoon of Castro strangling the Klansman, you have a sketch of a Castro-like figure who is offering his beard to cover up a naked black childlike figure. Revolutionary cartoonists in the 1960s go so far as to draw Castro strangling a Klansman but, at the same time, depict blacks as immature, childlike, and unfit for self-government in an image on the exact same page.

The longstanding—and often tense—relationship between Cuba and the United States has warmed considerably in the past year. In July 2015, the two nations restored diplomatic relations and President Barack Obama will travel to Cuba this month. From your perspective, what will the normalization of US-Cuban relations mean for the future of the island’s antiracist movement?

Benson: There is one thing that I often tell people when they ask me about this new “opening” between the U.S. and Cuba and how it’s going to affect people on the island. I tell them that Cuba has been open to the world since the 1990s. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Cuba had to change its economic policies. It had to open up to the rest of the world. In fact, the United States is really late coming into this game, because Cuba has already opened. It’s been changing economically, politically, and culturally in the past two decades through relationships with Canada and countries in Europe, Latin America, and Asia.

In terms of the future of the antiracist movement, I think it is really incredible how Afro-Cuban activists have really been able to make their movement more transnational. For example, Sandra Alvarez Ramírez, one of the women that I write about in the epilogue, runs a blog called Negra Cubana Tenía Que Ser [Black Cuban Woman I Had to Be], now lives in Germany and is doing her blog from Germany. I also know so many more Afro-Cuban activists and intellectuals who are now able to participate in international conferences that address racism and antiracist organizing. Because of the increased opportunities to travel abroad and access to the internet, I now see Afro-Cuban activists working with activists throughout the Americas, and I think that scholars and activists from the United States can become a part of that transnational conversation. However, I don’t think they’re going to be the ones who control it, because it’s already been going on and there are so many other places that have a lot of input, too.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.