The Trouble of Color: An Interview with Martha S. Jones

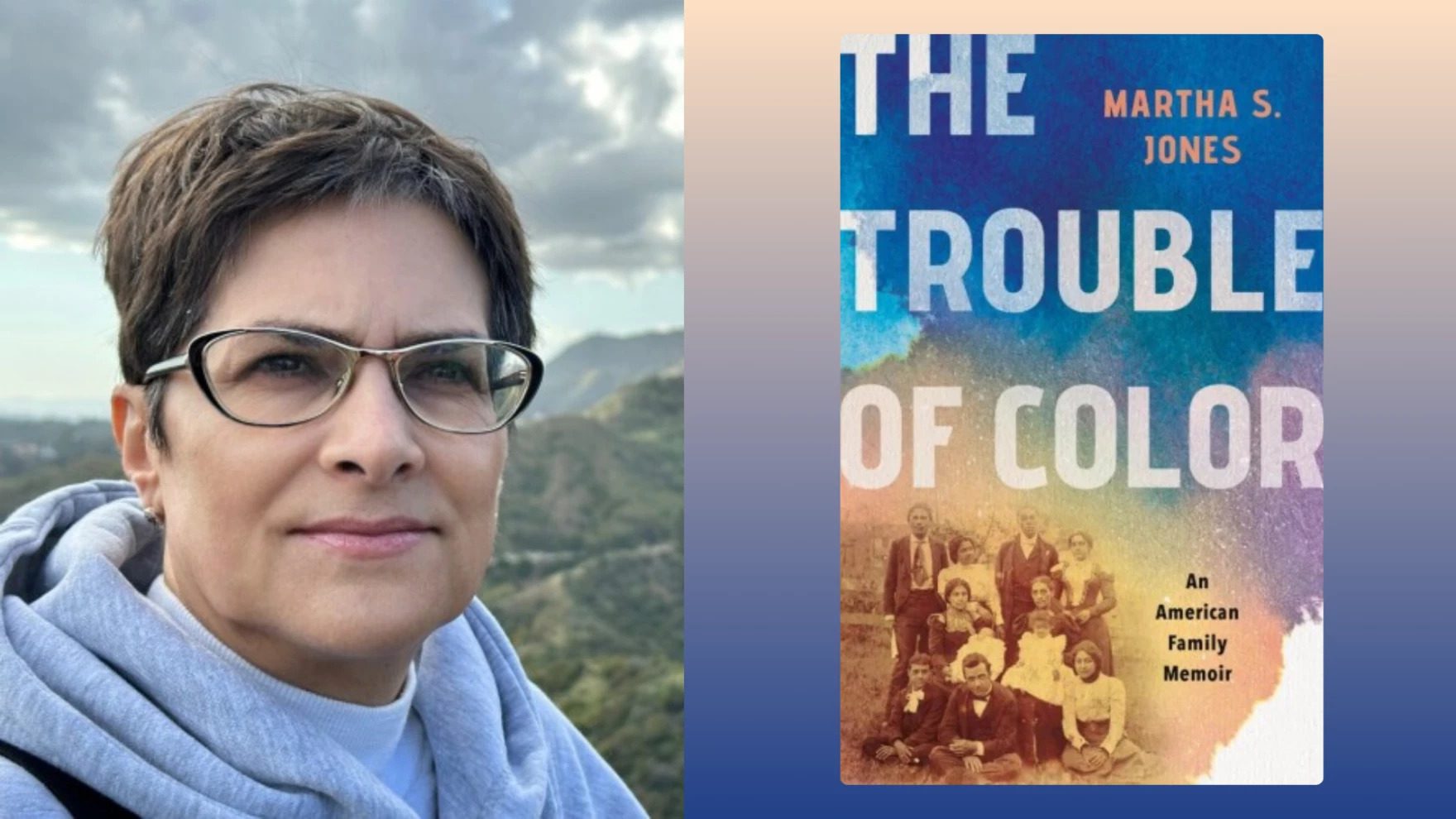

In today’s post, Dr. Robert Greene II, AAIHS President and Associate Professor of History at Claflin University, interviews Dr. Martha S. Jones about her latest book, The Trouble of Color: An American Family Memoir (Basic Books, 2025). Dr. Jones is the Society of Black Alumni Presidential Professor, Professor of History, Professor at the SNF Agora Institute, and Director of Graduate Studies at Johns Hopkins University. She has written extensively on the intersection of race, gender, justice, and the law throughout the full spectrum of American history. Dr. Jones has shared her work in numerous public-facing publications, including CNN, The Racial Imaginary Institute, The Atlantic, The New York Times, National Geographic, and The Washington Post.

Dr. Jones’ work has received praise from numerous circles, winning a variety of awards and changing how the public and academics alike think about the role of Black women in the American past. Her first book, All Bound Up Together: The Woman Question in African American Public Culture, 1830-1900, was published by the University of North Carolina Press in 2007. She also published the award-winning Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America, published in 2018, and Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted Upon Equality for All, published in 2020 and also the recipient of several awards. She also co-edited Toward an Intellectual History of Black Women, with Mia Bay, Farah J. Griffin, and Barbara D. Savage. Dr. Jones’ newest book tackles the complicated history of racial identity and passing in American history, through the fascinating story of her own family.

Robert Greene II: In the afterword of The Trouble of Color, you described your book as “a work of literature rather than history.” Why was it important to you to write a book that would not easily fit into categories such as history, and yet is so accessible to both historians and lay readers alike?

Martha S. Jones: First, thank you for the chance to talk about The Trouble of Color with you and with the followers of AAIHS and Black Perspectives (of which I am one!) I decided to write The Trouble of Color as a memoir only after realizing that history would not let me tell the story I was called to tell. Initially, I set out to render my family stories historiographically significant; this is how I had been trained. But those early efforts fell flat, and I asked myself what was missing. The answer was, it turned out, a depth of feeling. Not only did I aim to recount the story of our family, I also wanted to explore what it has felt like to be us, to live in our skin. Memoir offered me the space to introduce my own feelings, and to speculate, to hope and to dream with my ancestors. I had in mind memoir as exemplified by writers such as Kiese Laymon and Natasha Tretheway whose works showed me that not all truths are historical truths. I wrote The Trouble of Color while searching not for intellectual truths but for truths of the heart and of the soul; memoir let me discover that.

Greene: For historians of Black thought, the idea of passing—and what that means for individuals and families alike—has always been greatly intriguing. Why is the idea of passing so important to understanding the Black American experience, especially during the age of Jim Crow segregation?

Jones: This is an important question, but I want to be careful. Preparing to write a memoir meant that I did a lot of reading, including into the literature on passing. And while I can tell you how passing was important in my family, my conclusions are not sociological. The Trouble of Color invites readers to sit with one family’s experiences and try them on, compare them, and arrive at their own ideas about why passing has been and even continues to be important to them.

That said, I can share a few things that I learned after thinking about passing through a family lens. First, I came to appreciate that during Jim Crow a woman like my great-grandmother Fannie passed as a way to resist Jim Crow. Each time she sat in a white’s only theater seat or tried on a department store dress, she was getting one over on white supremacy. And in St. Louis, Missouri, where she lived, she was not alone. At the same time, within her own family, Fannie hurt those she loved. My own grandmother, Fannie’s oldest child, could not pass and until the end of her life bore the hurt that her mother’s downtown outings inflicted. On the days Fannie set out to pass, she left my grandmother at home; having her in tow would have given Fannie away. I came to know that these two sides of Fannie were both in their own way true: I both admire her militancy and resent her betrayal.

Fannie’s story led me to think that the term passing isn’t capacious enough to capture what it has meant for some of us to cross the color line. Passing to me still invokes those who crossed over and never looked back. I wish I had another word for those who, like Fannie, moved back and forth as a matter of circumstance but never abandoned their Blackness.

Today, my students say that someone who appears as I do is “white presenting,” and that this is different in degree from passing. If I am taken for a white person it is because, well, I can’t help that, is what I think they mean. I can’t say the phrase fits for me, but I appreciate that they are wrestling with language, trying to help us distinguish some forms of passing from others.

Greene: The geography of the experience of your family is something that stands out in The Trouble of Color. In particular, the state of Kentucky holds significant prominence for your family history. When we think of the history of Black America, what do you think is the importance of a border state like Kentucky to that history?

Jones: I enjoyed the challenge of persuading readers to care about places less fabled in our history, including central Kentucky and New York’s Long Island suburbs. By the time I take you to Greensboro, North Carolina, I am sure you have some inkling about the place, through mostly in the Civil Rights generation. Surprise! My story there is largely set in the 19th century. You asked about Kentucky, and that was the place I knew the least about going into the book. I traveled there for the first time while researching The Trouble of Color (and no one mistook me for a local). Your question referred to Kentucky as a border state, which is a nod to its political history: Slaveholding Kentucky remained part of the Union through the Civil War. But my story was not about the war. It was about a family.

In Central Kentucky, I learned, making families across the color line was widely practiced and openly acknowledged. There were some who condemned this fact and especially challenged the exploitation of enslaved women that was at the root of such families. Others, and this I learned from legal historian Bernie Jones’s study of Kentucky’s courts, regarded those same families as legitimate enough that judges allowed white men to free and then pass property down to enslaved women and their children. This was not a benevolent regime; it was one that honored the wishes of elite white men even if that meant also siding with the interests of Black women and their so-called mixed-race children.

This mattered in my family story. Our origins go back to unrecorded but wholly evident episodes in which enslaved women bore children by free white men. That past is written on our skin. What learning more about central Kentucky families helped me better understand is how the women in my family both remembered their exploitation and also regarded some white people as kin. The Trouble of Color not only permitted me to understand how, generations before, Black and white people in central Kentucky felt themselves to be relations. It also taught me how much has changed in our time: Even knowing more of the story, it has never occurred to me to think of those white slaveholding men and their descendants as kin. It is one of the lessons, for me, of family history: Each generation has had its own distinct story to tell about who family is and what that means.

Greene: Bennett College holds an important place in your family history. Your grandfather, David Dallas Jones, was President of that college. How are schools such as Bennett important to Black history—and, in particular, Black intellectual history?

Jones: My grandfather led Bennett from the 1920s through the 1950s and, while I was born only after he passed, I wasn’t but weeks old the first time I spent a summer on the campus. My grandmother lived the rest of her long life there and most years, when school ended, my parents sent me to be with her. I am indebted to the entire Bennett community for helping raise me up with a keen sense of Black history and why it matters. Writing The Trouble of Color gave me a chance to look further back to the years my grandfather led the school. Striking to me was how many towering black thinkers graced the campus, often during Sunday vespers, making students part of living Black history.

Some Black Perspectives readers will know that Bennett, when Greensboro’s leaders faltered, hosted Martin Luther King, Jr., there in 1958. The credit for that goes to Dr. Willa Player who succeeded my grandfather as president. Dr. Player was continuing a tradition; Bennett hosted figures who may not have been welcome elsewhere in the city or the South. I was especially interested in E. Franklin Frazier’s visit in the fall of 1945; Frazier and my grandfather had known one another since the 1920s when they were just beginning their professional lives. Historian Jelani Favors has chronicled the years that followed, helping me to understand the significance of what these men did through their connections, HBCU and otherwise.

By the time of that visit, Frazier and my grandfather were both targets of those in Washington who were hunting for “un-Americans” “subversives.” At Bennett, my grandfather held firm and continued to welcome Black thinkers. In the season of Frazier’s visit he also hosted Morehouse College’s Benjamin Mays, Max Yergen, head of the Council on African Affairs, and Howard Kester who led the Penn Normal and Industrial School in South Carolina. In that one semester alone, young women at Bennett, along with faculty and staff not only heard remarkable ideas. They learned what it took to build and sustain an intellectual community even in times of weighty oppression.

Greene: Throughout the memoir, you take great pains to explain the process of researching in the archives. Why was it important to you to lay out how you did your research, and how it personally impacted you?

Jones: One of the stories that runs through The Trouble of Color is that of me, a researcher and descendent. As a historian, I have largely left out the details of my research or relegated them to footnotes, a professional convention. Memoir permitted me to share my own research journey. Readers, I felt sure, were eager to see under the hood or behind the curtain to understand how we work.

I was drawn to go a step further. I am a full character in The Trouble of Color, largely because at many turns people drew me into the story. Among them were librarians and archivists who blurred the distinction between past and present when they talked with me about family history. I could not stand outside or at the edges of the narrative, like a faithful chronicler. I let readers to know that I was deeply invested in the story, like perhaps only a descendant can be. I challenge readers to consider that as a writer I can be both deeply invested and sincerely trustworthy as a narrator. For me, all this was a radical and welcome departure from how demands of objectivity and neutrality still echo through our work as historians.

Greene: Recently, Germany agreed to return the remains of 19 Black Americans used in race science research in the late 19th century. In The Trouble of Color, you recount interacting with the remains of members of your own family tree in archives. Why does the issue of human remains tucked away in archives seem to especially impact Black Americans and the understanding of their history?

Jones: On the politics and ethics of human remains, my first lessons came from the work of Native American activists and scholars who have developed important legal and cultural approaches to those institutions that hold sacred human remains in their collections. While I was discovering locks of my grandmother’s hair in the collection of Harvard’s Peabody Museum, that same institution was grappling with its obligation to repatriate human remains and sacred artifacts to Native American communities and demands for the return of the so-called Agassiz daguerreotypes to the family of Tamara Lanier. I approached the Peabody thinking that there was a bright line — human remains belong with families and communities.

My thinking expanded the more I learned about the circumstances under which my grandmother in the 1920s had provided samples of her own hair, and that of her oldest son, to a Harvard researcher. That researcher was also a Black woman and a friend to my grandmother, anthropologist Caroline Bond Day.

Unlike other of the human remains still held at the Peabody, I cannot say that my grandmother was coerced or misled, exploited or misused when she joined Day’s study. She endorsed Day’s aims, which were to disprove the theory of mulatto degeneracy. Like Day, my grandmother rejected the view that her mixed ancestry made her inferior, in any sense, and she sent her friend hair samples to help prove that. Now, today Day’s methods are understood to be without merit. Still, I came away appreciating that she, my grandmother, and other of the study’s participants, including W.E.B. Dubois, at one time believed that their version of race science might save them.

Greene: Your previous two books, Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America (2018) and Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All (2020) both dealt with critical questions of racial identity and democracy in American life. The Trouble of Color also approaches these topics, albeit from a deeply personal level. Why are these themes so important to you as a historian of the Black experience?

Jones: I wish I could tell you that my work has emanated from an early and abiding commitment to critical questions of racial identity and democracy in American life. What you say is evidently true, but I cannot say that has come about by design. One of the great gifts of this work for me has been how it affords me the latitude to follow my nose. Birthright Citizens was born out of my years as a lawyer in local courthouses, a place in which I believed epic stories were lived out each day. I tried to show how that was true even in the 19th century and even for a question as important as citizenship. Vanguard was written on the offense. I knew that in 2020 the US would mark 100 years since ratification of the 19th or so-called women’s suffrage amendment and I wanted to be sure that Black women were not overlooked during those celebrations. I was sometimes perceived as a wet blanket, someone who suppressed the upbeat spirit of the occasion by inserting the fact of anti-Black racism within the struggle for women’s votes. I tried to welcome that role.

The Trouble of Color is the book I’d always hoped to write. I didn’t have the insight or the writing chops to attempt it earlier in my career. For me, it mattered that I was a seasoned historian of Black American and US history generally when it came time for me to finally frame my family by way of the past. And I had to be willing to learn to write — again! The Trouble of Color has no footnotes, I’m sure you noticed, and that was intentional. I wanted to write in a style that put it all on the page. Either you are with me there or you are not with me. There are no back up or second chance notes at the end that might persuade you. I’m indebted to my editors and the friends who read early drafts. They pushed me to give my all to the words on the page.

Most remarkable and perhaps equally regrettable is how some of my earlier work has remained relevant. For Vanguard, that meant reviving that book when Kamala Harris made her historic run for the presidency in 2024. When it comes to Birthright Citizens, that book has had a life much longer than I would have wished. It came out in 2018, just as then President Trump first called for ending birthright. As we know, he has renewed that call and acted upon it now in 2025. It has been an honor and I hope of use to share the fuller history of the birthright principle as one originated and held up by Black Americans during the many decades during which they were denied the fundamentals of citizenship. It matters, I hope, as we watch the administration attempt to return to a regime in which lawmakers might arbitrarily single out who can be a citizen and by what terms. As Blackness once disqualified Americans in the 19th century, on the table and in the courts today is an attempt to make the status of ones immigrant parents similarly disqualifying. Here, as is true for so much of our past, Black history tells the rest of the story. If there is one thread that runs through all my work it is that: Black history matters.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.