Why Black Teachers Matter

A recent Mother Jones article entitled “Black Teachers Matter” focused on the dwindling number of African American teachers, using the city of Philadelphia as a case study to illustrate a national challenge: high rates of turnover among black K-12 educators. Mother Jones reported the following statistics describing the problem:

- “the turnover rate for white teachers has been relatively stable at 15 percent since the 2008-09 academic year.”

- “the departure rate for black teachers has been increasing, from 19 percent in 2008 to 22 percent in 2013—a higher turnover rate than in any other demographic.”

- “the biggest factors teachers of color cite for leaving…are micromanagement and lack of autonomy in the classroom.”

- “At the beginning of the 2003-04 school year, about 47,600 educators of color entered teaching; the following year, 20 percent more—about 56,000—had left teaching.”

According to the logic of neoliberal education reform that is currently driving the deprofessionalization (“micromanagement and lack of autonomy”) of teachers and the privatization of K-12 and higher education, the identity of a teacher should be irrelevant to their ability to deliver a standardized curriculum to students. Why, then, should there be any concern about the attrition of black educators?

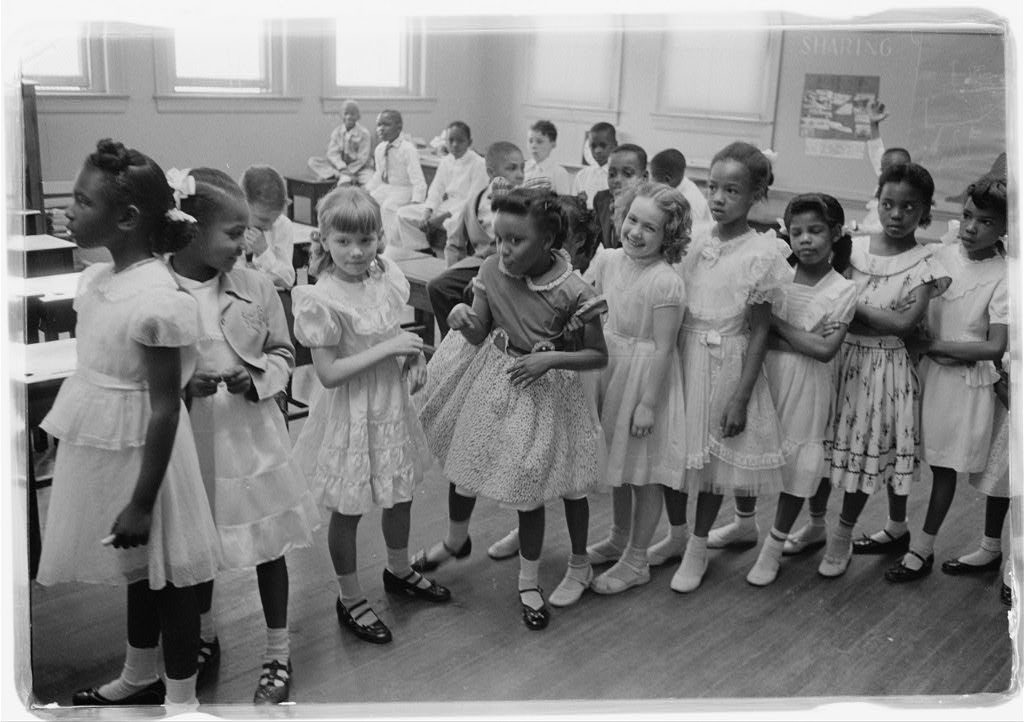

As a historian of education, I look backward for answers to contemporary educational questions. The Mother Jones article reminded me of an essay that W.E.B. Du Bois penned in 1935, entitled “Does the Negro Need Separate Schools.” Du Bois surmised that separate schools for black children “are needed just so far as they are necessary for the proper education of the Negro race”—with “proper education” consisting of a sympathetic touch between teacher and pupil; knowledge on the part of the teacher not simply of the individual student, but of his surroundings and background and the history of his class and group; contact between pupils, and between teacher and pupil, that will increase this sympathy and knowledge on the basis of perfect social equality; facilities for education in equipment and housing; and the promotion of extra-curricular activities that will tend to induct the child into life.

Holding this definition in mind, and considering what he observed to be “the present attitude of white America toward black America,” Du Bois concluded “the Negro not only needs the vast majority of these schools” but it was quite possible that future generations of black people would “need more such schools, both to take care of his natural increase and to defend him against the hostility of the whites.” In other words, he did not believe that the antagonism of white Americans toward black Americans recommended the former as appropriate teachers for the latter. Black teachers, he asserted, were best equipped to give black children a compassionate, identity-affirming education at that moment in history.

Eighty years removed from Du Bois’s essay, it can be tempting to assert that his conclusions painted the prospect of mixed school settings for black children in an overly pessimistic light. But recent educational research indicates that his concern about the impact of white teachers on black students may point to an enduring dynamic in the classroom.

The Mother Jones article appeared amidst a flurry of new studies on the significance of teacher race on student academic outcomes and research on the implicit bias that colors teachers’ perceptions of even the youngest black students. These studies refute the colorblind ideal underpinning present-day race-neutral education reform.

In this context, it becomes important to think about why race matters in the classroom, or, more precisely, what are the practices of teachers of different racial backgrounds? Does racial essentialism fuel, for instance, the tendency of black teachers to identify black students as gifted when white teachers might overlook them? Or do these teachers operationalize practices and beliefs that all teachers can learn from?

For answers, again, I turn to history, to the works of Vanessa Siddle Walker and the original research of Derrick Alridge’s Teachers in the Movement Project at the University of Virginia. Focusing on educators in segregated and desegregating schools at mid-century, these scholars have examined and worked to codify the educational thought and practice of African American teachers during that era. These scholars demonstrate the strategic nature of these teachers’ pedagogy and their status as consummate professionals, and often as intellectuals.

This history of highly qualified black educators should be a major part of the backdrop when considering the present-day attrition of black teachers—as well as the reality that desegregation frequently meant massive job losses for African American teachers and principals, with adverse consequences for black students. The educational upheavals of the 1950s and 1960s demonstrate that the presence—and the absence—of black teachers matters greatly.

Lindsey E. Jones is a PhD Candidate in History of Education at the University of Virginia’s Curry School of Education and a 2016-2018 Pre-doctoral Fellow at the Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American and African Studies at the University of Virginia. Her dissertation project, “‘Not a Place of Punishment’: the Virginia Industrial School for Colored Girls, 1915-1940,” historicizes the education and incarceration of black girls by examining Virginia’s only reformatory for delinquent African American girls. Follow her on Twitter @noumenal_woman.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

Is this an argument for segregation? I am shocked…but it is even more shocking than people are not discussing this a lot more. I am very glad that you wrote this article!

What a compelling discussion. I wonder if there is data that shows historically, Black teachers have not been able to assert culturally-relevant approaches with Black students, which may be one reason for the high turnover. So proud of your work Ms. Jones.

I have been discussing the fact that “others ” teach our children that they are disadvantaged and ate less than from the early years to the high school years with very little encouragement. We need black educators to return to the schools so that our children can have a fair chance to succeed in a system that is systemically set up to fail them!

Racism in the United States has always been based on economic suppression. The main objective was to keep persons of color marginalized, and lacking the ability to advance beyond their white counterparts. This goal continues and remains successful when African Americans linger in professional employment, or receive lesser pay for greater work. Let’s face it black educators are treated as dispensable. Black educators are often presented with a take it or leave plight and can find themselves without work if they choose the latter. The lack of African American teachers, in mass numbers, earnings and rankings at equal levels of white educators is devastating. Sadly to say it’s intentional and systematic. School’s boast of having diverse faculty, but It’s not diversity when there is only one African American faculty member in the program, or department that teaches: African Studies, African Lit, African History, Women Studies or the like. It’s even becoming a norm in highly populated black areas, and yes HBCUS throughout the south. I know of three. Also, let’s not forget the lack of African Americans on college boards, or serving as college presidents, school deans, and department heads.

One other thing, let’s not forget all the state schools and federally funded universities that don’t have, “Black Studies Programs” in history, literature, or the like. These same schools, have never had an African American president -or so few hard to track- and have very few African Americans, if any serving on the colleges’ board of directors. Many of these schools have a significant number of African American students.I’ve have been in the academy for over ten years and have heard numerous complaints from mentors, colleagues, and former classmates. This will change only when African American scholars are viewed equally important as their white counterparts. This remains a civil right issue of today. Equal pay for equal work!