The Hip Hop Pedagogy and Innovative Prose of Rakim Allah

It was the summer of 1986 in Chicago, and my eleven-year-old self was engaged in an intense debate with my buddies after little league practice. The topic of debate was hip hop. We were debating who was the coldest emcees of the day with the hottest albums out–cassettes to be exact–at the time. LL Cool J was at the top of the list. Run DMC was tossed around and so were Kool Moe Dee, Fat Boys, and Beastie Boys. The discussion took a different path when one of my teammates remarked, “But yo, y’all heard of this dude named Rakim?” We were all puzzled. As we prodded our teammate with extreme skepticism, his older brother arrived to pick him up from practice bumping (unbeknownst to us) the classic, ‘My Melody.’ My teammate shouted, “That’s Him…That’s Rakim, the dude I was telling y’all about.” We couldn’t believe our ears and definitely couldn’t’ believe that it was rap. I had never heard anything like it before, and honestly, I had no idea that hip hop was capable of arresting me in this way. After hearing the emcee known as Rakim Allah I fell in love with rap and became fixated on the art of the emcee.

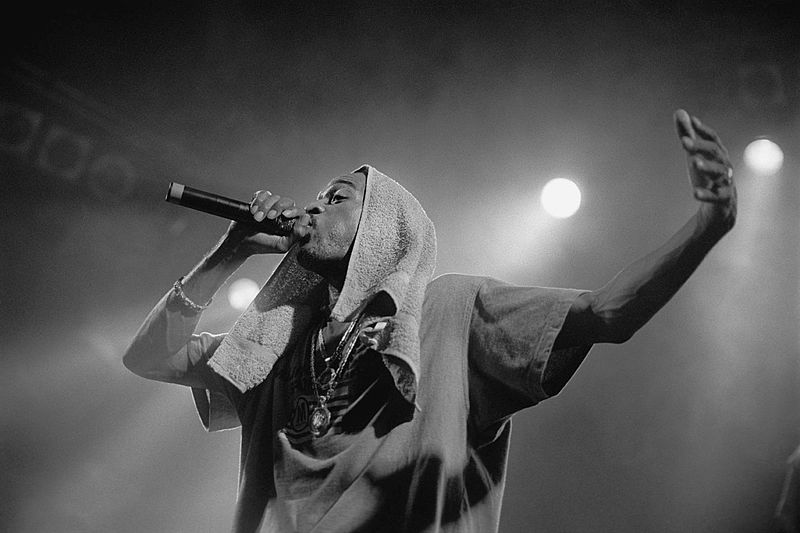

The duo Eric B & Rakim, consisting of Eric B the deejay and Rakim the emcee released their debut album, ‘Paid in Full’ in August 1987 during hip hop’s ‘Golden Era.’ Their album’s release ushered in a new era for ‘rap’ now defined by the creative new rhyme style of Rakim Allah. From rap’s inception up until the mid 1980s, practitioners of the art form offered a simpler form of lyrical expression that became synonymous to general hip hop fans. Rakim, with his combination of cadence, flow, content, stage presence, rhyme construction and overall melodic interface, transformed the art of rap, but most importantly, the function of an emcee. According to historian Jelani Cobb, the entry of Rakim “heralded the arrival of a whole ‘nother approach to the form, so radical a disjuncture with what had come before it, that it could literally hurt your head thinking about it.” Rakim’s arrival established a line of demarcation in hip hop that essentially became the standard by which all prospective newcomer emcees came to replicate.

A product of Wyandanch, Long Island, Rakim was born William Michael Griffith to a musical family. His mother Cynthia Griffin was a jazz and opera singer, his brother Steve Griffin was a pianist, and his aunt Ruth Brown was a legendary R&B singer. Growing up playing the saxophone, a young Rakim was taught the essentials of music theory and his teen years were largely influenced by the mystical jazz of John Coltrane and Thelonius Monk, the legendary emcees Melle Mel, Kool Moe Dee, and Grandmaster Caz and the Five Percent teachings of Clarence 13X. During the mid-1980s, he converted to the Five Percent Nation (also known as the Nation of Gods and Earths) and adopted the name Rakim Allah to reflect his Islamic beliefs.1 During this period, Rakim collaborated with Eric B. to produce the 12” single, “Eric B is President” with the legendary B-side, “Check out My Melody” that produced the classic lines of the ‘seven emcees’ to Rakim’s boasts of having the linguistic power to “break New York from Long Island.”

A self-proclaimed microphone fiend, Rakim’s laid-back flow, complex rhyme schemes, and frequent use of the Caribbean calypso form of talking and chanting over a beat conjure the historical memory and genealogy of the Black Arts Movement. Writers and spoken word artists such as Gil Scott Heron, Sonia Sanchez, The Last Poets, and the Hustler’s Convention by Jalal Mansur Nurridin all utilized various aspects of these elements in their works. Enthralled by the creative innovation and spontaneity of John Coltrane’s ability to execute two distinguishable notes simultaneously, Rakim embarked on an approach to lyricism that attempted to transcend simplistic rhyme schemes with a writing technique that fused the improvisation of jazz with a scientific writing structure to capture such creativity.

Utilizing an eccentric writing technique to mimic the improvisation of jazz and construct his verses, Rakim would plot sixteen dots on a blank sheet of paper to represent a sixteen bar rhyme. With each bar, his objective was to fill each rhyme bar with multi-syllabic word patterns that benefited from rhyme alliteration and complex metaphor. A quintessential Gotham emcee, Rakim drew from a ‘New York state of mind’ when developing content for his songs that found him delivering ‘Lyrics of Fury’ to his fan base while reminding both his hip-hop peers and prospective emcees to ‘Follow the Leader.’

While giving birth to an unprecedented rhyme style, Rakim’s cool pose approach offers significant ancestral connectivity that emanated from the West African griot, whose job was to keep memory and retain the oral tradition of telling stories. This is evident in his lyricism on songs like ‘The Ghetto,’ where he remarks,

Reaching for the city, a Mecca, visit Medina

Visions of Nefertiti then I seen a

Mind keeps traveling, I’ll be back after I

Stop and think about the brothers and sisters in Africa

Return the thought through the eye of a needle

For miles I thought and I just fought the people

Under the dark skies on a dark side

Not only there but right here’s an apartheid

Rakim as an emcee embodied these critical qualities for the purpose of achieving the goal of sonically arresting his audience, while also being able to ‘Move the Crowd.’ With an unbridled ability to flow, Rakim’s presence as an emcee also provided Black youth with a form of retreat during hip hop’s ‘Golden Era.’

However, the era most admired by hip hop fans cannot be glossed over in total celebration, as it was the decade most crucial to the expenditures of Black life that marked the crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s. Trickle-down economics and the gross socioeconomic disparities created by Reagonomics ushered in Draconian drug penalties, which had devastating effects on the Black community during this period. And with the elimination of arts programs in public schools, Black teens needed the counter-narrative voice of hip hop as a means to retain their humanity. As an emcee, Rakim provided such a voice with his lyrical creativity during a period of structural inner-city blight throughout the US.

According to to Black revolutionary writer and activist Amiri Baraka, “the Black Artist must draw out of his [her] soul the correct image of the world. He [She] must use this image to band his [her] brothers and sisters together in common understanding of the world (and the nature of America) and the nature of the human soul”2 I would add that the Black artist’s role is also to intentionally educate and advocate for the progression of a people. And as an artist, the role of an emcee should be to steward such an undertaking through verse, rhyme, and flow. Rakim provided such an experience.

Like many other hip hop fans, I celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of Eric B. & Rakim’s magnum opus, “Paid n Full,” which was Rakim’s grand introduction. Rakim is the epitome of a paradigm shift and the evidentiary proof can be found in the diverse bodies of work and music from the plethora of emcees produced after Rakim’s inception in 1986.3 His inception meant that a young Black boy from the South Side of Chicago could have admiration of poetic expression as displayed through hip hop. Rakim demonstrated that it was cool to utilize various units of language for simple and complex unapologetic self-expression of love, imagination, humanity and most importantly, Black soul.

- Jeff Chang, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation (New York: Picador, 2005), 257-258. ↩

- Leroi Jones (Amiri Baraka), Home: Social Essays (Brooklyn, NY: Akashic Books, 2009), 281. ↩

- The style of emceeing Rakim pioneered can be found in the music of Black Thought, Nas, Jay-Z, O.C. Bahamadia, Elzhi, Lauryn Hill, Pharoah Monche, Jadakiss, Jean Grae, Raekwon, J. Cole, Rhapsody, Nick Grant, Kendrick Lamar and countless other hip hop artists whose contributions to hip hop culture directly reflect the style and prose of Rakim Allah. ↩

Fascinating take on a fascinating emcee. msh